Evaluation of the Banting Postdoctoral Fellowships Program

Final Report 2015

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to all the participants in this evaluation – survey respondents, interview and focus group participants, the Vanier-Banting Secretariat, CIHR Financial Planning Unit, and CIHR Planning, Reporting, Measurement and Data Unit. Additional thanks to Jean-Christian Maillet and Adnan Al Wahid (CIHR Evaluation Unit) and members of the Evaluation Working Group – Shannon Clarke-Larkin (NSERC/SSHRC), Tony Damiani (Industry Canada), Christopher Manuel and François Zegers (CIHR).

The Banting PDF Evaluation Team:

Kwadwo (Nana) Bosompra, Michael Goodyer, David Peckham.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

160 Elgin Street, 9th Floor

Address Locator 4809A

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0W9

Canada

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Performance

- 3. Relevance

- 4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendices

- References

Executive Summary

Program Description

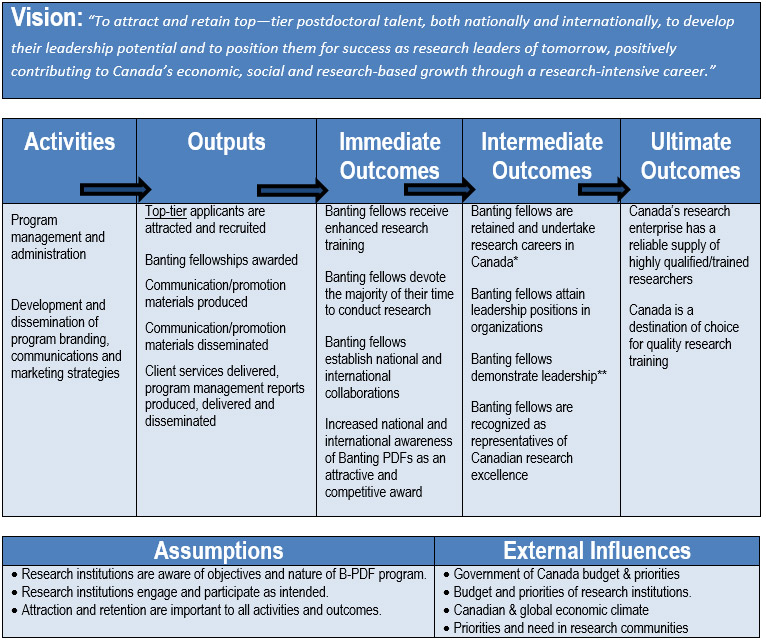

The Banting Postdoctoral Fellowships (PDF) program was launched by the federal government in 2010 as part of a broader strategy to increase Canadian capacity for research excellence. It was designed as a prestigious postdoctoral fellowship program that would attract top-level talent to Canada. The program’s specific objectives are to:

- Attract and retain top-tier postdoctoral talent, both nationally and internationally;

- Develop their leadership potential; and

- Position them for success as research leaders of tomorrow.

The value of the Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship is $70,000 per year for a two-year period. The program awards 70 fellowships annually which are distributed equally among the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). The Banting PDF program is unique in its emphasis on the synergy between the applicant and the host institution, with applicants required to complete their applications in full collaboration with the proposed host institution. The program is administered jointly by the CIHR, NSERC and SSHRC.

Evaluation Purpose, Scope and Methodology

The purpose of this first evaluation of the Banting program is to assess the program’s continued relevance and performance (effectiveness and efficiency), and how it can be improved. The evaluation was led by CIHR in collaboration with NSERC and SSHRC and covers the first four competitions of the program from fiscal year 2010-11 to fiscal year 2013-14.

In line with best practice in evaluation, multiple lines of evidence were used to triangulate the findings, including: review of program documents and administrative data; key informant interviews; focus groups with Banting recipients and applicants; online surveys of Banting recipients, unsuccessful applicants and selection committee members; and bibliometric analysis of Banting applicants’ research productivity and impact. The evaluation compared Banting fellows with two different groups of unsuccessful applicants: those who obtained a postdoctoral fellowship from CIHR, NSERC or SSHRC (referred to throughout this report as “Agency PDFs”) and those who did not obtain a postdoctoral fellowship from any of the tri-agencies (referred to as “Unfunded” applicants.)

Key Findings: Performance

Attracting and Selecting Top-tier Candidates

The Banting PDF program is attracting and selecting top-tier candidates.

- Selection committee members ranked Banting applications among the best they had reviewed in comparison to similar programs and strongly believed in the ability of the Banting PDF selection process to pick the best candidates.

- Bibliometric analysis of the impact of publications showed that applicants in the health sciences and natural sciences and engineering domains had higher average of relative citation (ARC) scores and higher average of relative impact factor (ARIF) scores than the average for Canadian and World researchers. This evidence supports the view that the program is attracting some of the best researchers in the world.

- This evaluation has highlighted a potential tension between the program objective of attracting top-tier talent and that of retaining it. The design of the program results in both an ‘inflow’ into Canada of top-tier foreign citizens coming to Canadian institutions and an ‘outflow’ of Canadians and permanent residents who take up their awards abroad. In simple terms, this can be viewed as a ‘net gain’ or ‘net loss’ of top-tier talent, although there are many further nuances to consider (e.g. Canadians who later return to this country). To prevent a ‘net loss’ of talent, the program stipulates a 25% annual cap on awards held by Canadians outside of Canada.

- The annual cap has resulted in a small proportion of top-tier talent not being selected for awards. During the period under review, ten Canadian applicants proposing to take up awards abroad (4%) were passed over as a result of this annual cap, with an additional eight being passed over in the most recent (2014-15) competition.

- The program has resulted in a greater number of foreign citizens coming into Canada than Canadians leaving to go abroad; 31% of those taking up awards were foreign citizens coming to Canada (87 awards) compared with 25% who were Canadians or permanent residents hosted abroad (71 awards).

- There is a lack of consensus regarding the need for the cap among supervisors, host institution representatives, federal agency representatives, and selection committee members. Some stakeholders do not want to limit the take-up of the award internationally while others see a need for limits to retain postdoctoral fellows in Canada.

- There are signs of a decline in the proportion of foreign applications; after initially holding steady at 40%, this fell to 34% in the last year under study, and further to 26% of applications in the most recent competition (2014-15). One possible explanation is that the requirement to demonstrate synergy between an applicant’s research program and the proposed host institution’s strategic priorities may be posing a barrier to foreign applicants.

Training and Support

Banting fellows rate their training environments very highly and are receiving appropriate training and support to carry out their research programs. Some Banting fellows seemed to be accessing additional supports, usually resulting from institutional commitments made as part of their application. There is wide variation in the additional supports provided by host institutions; examples include being given the opportunity to apply for research grants as an independent investigator and being appointed into a senior trainee position. This variation in types of support may have an impact on the ability of Banting fellows to conduct independent research.

Research Excellence and Leadership

Available evaluation evidence suggests that Banting fellows are demonstrating research excellence as well as leadership after receiving the award. Bibliometric analysis indicates that after receiving the award, Banting fellows in the health sciences and natural sciences and engineering had higher ARC and ARIF scores than their respective cohorts of Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants.

- Fellows’ supervisors and senior representatives of host institutions saw the Banting fellows as strong research leaders and change agents.

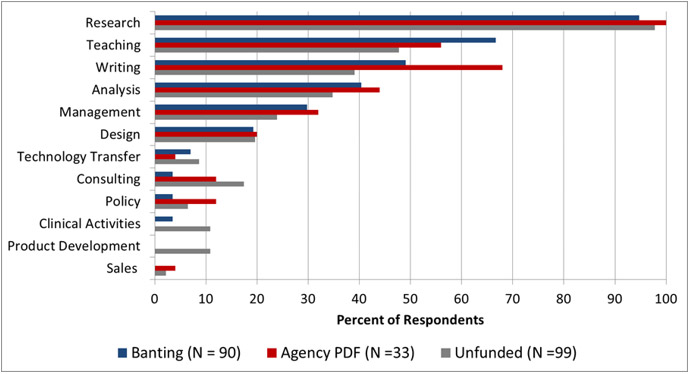

- Banting fellows spent over two-thirds of their time on research and less on teaching, supervision, administrative tasks and other activities; these proportions were however, similar to those of Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants.

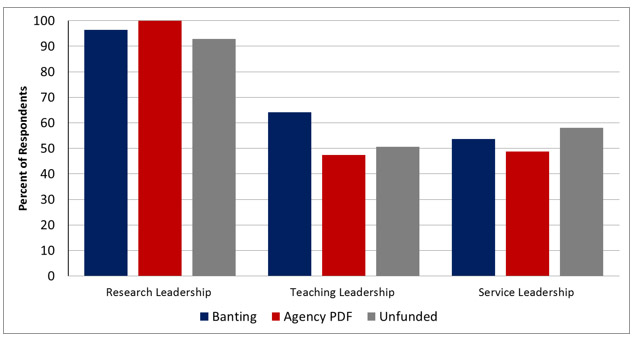

- Almost all Banting fellows, Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants believed that their research leadership abilities had developed to a great extent or some extent as a result of their postdoctoral training. However, only half of each of these three groups held a similar perception about the extent to which their teaching and service leadership abilities had developed during their training.

- As compared to research leadership development activities, Banting fellows were less likely to engage in teaching leadership development activities and least likely to engage in service leadership development activities.

Establishing Collaborations

Banting fellows are establishing collaborations, most frequently within their own institutions and internationally, which are ongoing and resulting in the production and dissemination of knowledge.

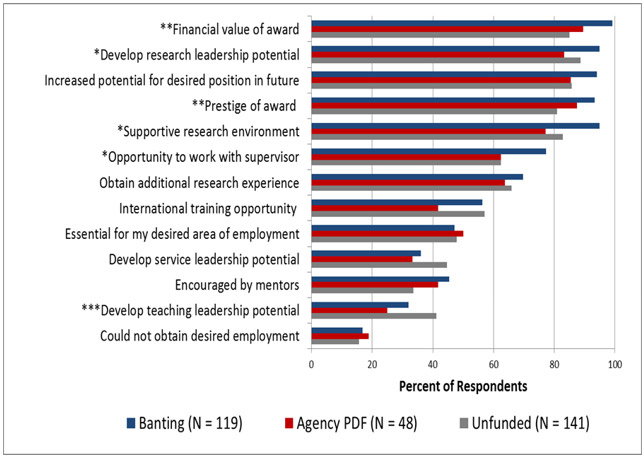

Awareness of Banting Fellowships

Evaluation evidence indicates that awareness of the Banting fellowship is increasing both nationally and internationally; however, the program is currently better known in academia and in Canada. The fellowship is highly regarded by applicants, particularly for its award amount, prestige and opportunities to develop their research leadership potential.

Retention of Banting Fellows

Although the evaluation covers only the first four years of the program, there is evidence that the program has made progress towards meeting its intermediate objective of retaining top-tier postdoctoral talent in Canada.

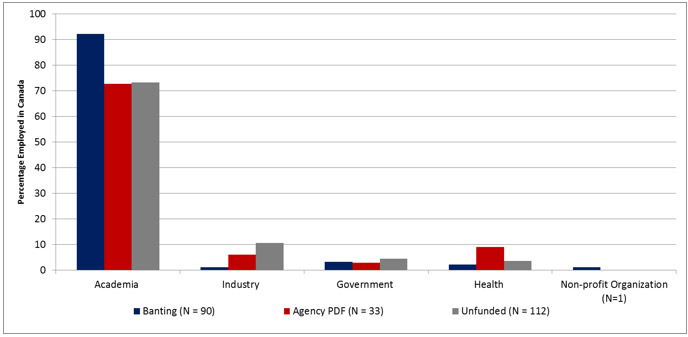

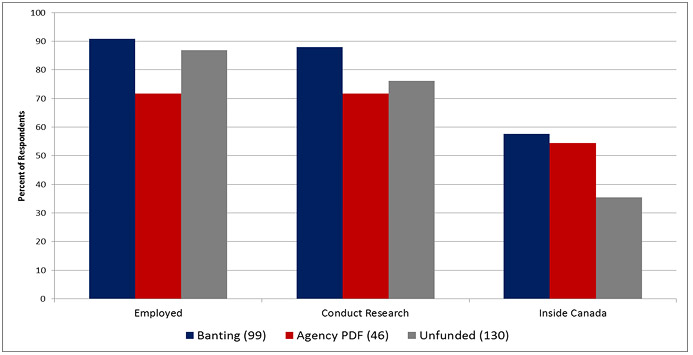

- Banting fellows are more likely to be: employed (91%), conducting research (88%) and working in Canada (58%) than Agency PDFs (72%, 72% and 54% respectively) and Unfunded applicants (87%, 76% and 35% respectively).

- A greater proportion (92%) of Banting fellows work in academia compared to Agency PDFs (73%) and Unfunded applicants (73%).

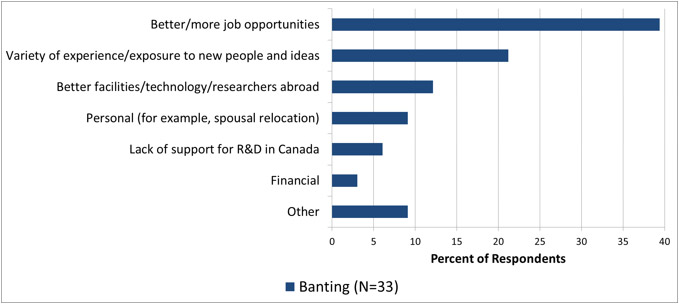

- Among those working outside Canada, the most common reason for pursuing research-related positions outside the country was for better or more job opportunities; this finding is also consistent with the views of key informants.

Program Efficiency

Available evidence indicates that the Banting program is being delivered by the federal research funding agencies in a cost-efficient manner.

- For fiscal year 2013-14, the administrative expenditure ($434,340) as a percentage of total expenditure ($10,234,340) was 4.2% which translates into an administrative cost of $1,000.78 per eligible application and $6,204.85 per award.

Key Findings: Relevance

The evaluation confirms the continued need for the Banting program to support and develop Canada’s postdoctoral talent pool. The program is attracting top-tier postdoctoral talent and serving as stepping stone or pathway to an academic career.

The Banting program aligns with federal roles and responsibilities to support the attraction, development and retention of researchers and is consistent with the federal government’s approach to supporting research capacity as outlined in the 2014 Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy. The program also aligns closely with the strategic outcomes and priorities of CIHR, NSERC and SSHRC to build research capacity by attracting, supporting and training top-tier postdoctoral fellows to carry out research.

Conclusions

Overall, the Banting PDF program is meeting or has made good progress towards meeting its immediate outcomes. There is evidence that top-tier postdoctoral trainees are being attracted, recruited and provided with some enhanced training and support, although this support varies across host institutions. There is awareness of the program particularly within academia and nationally. Banting fellows are devoting majority of their time to research and are establishing national and international collaborations that are resulting in the creation and dissemination of knowledge.

The program has only just completed its fourth year but has already made progress towards achieving its intermediate outcomes of demonstrating research excellence and retaining top talent in Canada. Banting fellows are beginning to show development in leadership particularly in the research domain and are more likely than comparator groups (Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants) to be employed and conduct research in Canada. Banting fellows are being recognized by both senior representatives of host institutions and fellows’ supervisors as exceptional, outstanding, and driven. There is also evidence that the program is being delivered in a cost efficient manner.

The evaluation evidence attests to the continued need for the Banting PDF program and the program’s alignment with federal roles and responsibilities and with the strategic outcomes and priorities of the federal government, and CIHR, NSERC and SSHRC.

Recommendations

The Banting PDF program has made good progress towards achieving its intended outcomes and based on the evidence of this evaluation should be continued. The following recommendations address issues that could affect the performance of the program going forward, with supporting evidence provided for each of these.

The Banting program should take steps to address the decline in international applicants to ensure the program can attract and retain top-tier postdoctoral talent, both nationally and internationally.

The proportion of foreign applications fell from 40% in the program’s first two years to 34% in the last year under study, and declined further to 26% of applications in the most recent competition (2014-15). Additionally, in the 2014-15 competition, 146 foreign citizens (not permanent residents) applied for the fellowship, approximately half (56%) of the 260 foreign citizens who applied in the first-year of the program (2010-11). Key informants suggested the program might be too Canada-centric and that Canadian professors would be unlikely to nominate a candidate with whom they had not previously worked. This could potentially put international applicants at a disadvantage. Banting program management should explore any potential link between the decline and program design issues such as the requirement to demonstrate synergy between an applicant’s research program and the proposed host institution’s strategic priorities. Program management should also review current processes used by universities to determine if factors exist that inhibit international applications and, if warranted, take action to address the factors.

The Banting program should monitor the ongoing impact of and need for the 25% cap on Banting fellowships awarded to individuals who apply in collaboration with a foreign institution.

The issue of the 25% cap relates to the tensions identified in the program between the attraction and retention of top-tier talent. Decisions taken on the cap will reflect whether program management views it as more important to attract the best candidates regardless of where they intend to take up the award or whether ensuring retention and a ‘net gain’ of talent is the primary consideration. While the cap contributes to the retention of top-tier postdoctoral talent in Canada it limits the selection of the best candidates from among those who wish to hold their fellowship abroad.

There is currently a lack of consensus among key program stakeholders on the need for the cap and diverse opinions on the benefit to Canada of retaining Banting fellows to conduct their training in Canada in contrast with the international nature of research and ability to attract top-tier postdoctoral fellows. As a result, it is important to monitor the attraction and retention of Banting fellows after their fellowship to assess the need for the cap based on its longer-term impact on the retention of Banting fellows.

The Banting program should develop guidance regarding leading practices for the support of Banting fellows to develop their leadership potential and position them for success as research leaders of tomorrow.

Currently, the nature and extent of support provided to Banting fellows varies widely across institutions, which could impact the ability of fellows to conduct independent research. Some supports such as office space, computers and access to library facilities seem to be always available but others such as a guaranteed fund for independent research or the ability to independently apply for research grants are not. Similarly, mentoring by fellows’ supervisors or informal interactions with other experienced faculty appear to be always available whereas formally structured mentorship programs with specified milestones are rare. The Banting program should identify leading practices regarding the level and types of support to develop and position Banting fellows as research leaders.

1. Introduction

About the Program

The Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship (PDF) program supports the development of Canada’s research capacity by awarding fellowships in equal numbers in the areas of health sciences, natural sciences and engineering, and social sciences and humanities. The program was announced in the 2010 federal budget as part of a broader strategy to increase Canadian capacity for research excellence and has the following specific objectives:

- Attract and retain top-tier postdoctoral talent, both nationally and internationally;

- Develop their leadership potential; and

- Position them for success as research leaders of tomorrow.

The fellowship program is expected to attract the very best applicants, both nationally and internationally, and candidates are required to apply in full collaboration with their proposed host institution showing the host’s commitment to their research program and its alignment with their strategic priorities. This requirement for institutional commitment and demonstrated synergy between applicant and institutional strategic priorities is unique to the Banting PDF.

Further details about the program including its target audience, delivery and budgetary resources are presented later in this report in Appendix A: Program Profile.

Evaluation Purpose and Scope

This is the first evaluation of the program and is designed to provide tri-council senior management with valid and practical findings about the performance and continued relevance of the Banting PDF program and meet the requirements of the Financial Administration Act and Treasury Board’s Policy on Evaluation.Footnote 1 The evaluation was led by CIHR in collaboration with NSERC and SSHRC.

The evaluation’s scope is limited to the first four years of the program, 2010-2011 to 2013-2014 and assessment of program performance focuses on the extent to which immediate outcomes have been achieved, what early progress has been made towards achieving intermediate outcomes (expected to occur in one to five years post award) and how the program can be improved.Footnote 2

In accordance with the Treasury Board Secretariat’s (TBS) requirements under the 2009 Policy on Evaluation and Directive on the Evaluation Function,Footnote 3 the evaluation addresses the core issues identified by TBS:

- Continued need for the program;

- Alignment with government priorities;

- Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities;

- Achievement of expected outcomes; and

- Demonstration of efficiency and economy.

Evaluation Questions

The evaluation addresses the following questions:

Relevance

- To what extent does the Banting program continue to address a demonstrated need?

- To what extent is the Banting program aligned with federal roles and responsibilities?

- To what extent is the Banting program aligned with federal government and agency priorities?

Performance: Effectiveness

- Is the Banting program’s selection process able to attract and select top-tier post-doctoral candidates?

- To what extent have Banting fellows received appropriate training and support to carry out their research programs?

- To what extent have Banting fellows demonstrated research excellence and leadership?

- To what extent have Banting fellows established national and international collaborations?

- To what extent have national and international awareness of Banting fellowships as an attractive and competitive award increased since program launch?

- To what extent have Banting fellows remained in Canada and pursued research careers?

Performance: Efficiency and Economy

- Are the most appropriate and efficient means being used to achieve the outcomes, relative to alternative design and delivery approaches?

Evaluation Methodology

Data Collection

In line with TBS guidance and recognized best practice in evaluation (e.g., McDavid, Huse & Hawthorn, 2013), several lines of evidence were utilized to triangulate the evaluation findings and ensure that conclusions drawn would be valid.Footnote 4 The data collection methods included the following:

- Key informant interviews (n=46) with Banting host institution representatives, Banting fellows’ supervisors; senior executives of the tri-agencies, Vanier-Banting secretariat and relevant federal government departments;

- Focus groups (n=5) with current Banting fellows and corresponding cohorts of unsuccessful applicants;

- Online survey of Banting selection committee members (n=60);

- Online survey of the first two cohorts of Banting fellows (using the Banting End of Award Report, BEAR) (n=119);

- Online survey of corresponding cohorts of unsuccessful applicants (n=189);

- Bibliometric analysis of the research productivity and impact of Banting PDF applicants from the first four competitions; and

- Analysis of administrative data and review of program documents.

Analysis Approach

The analysis compared Banting fellows with two groups of unsuccessful applicants: those who had received an Agency-specific postdoctoral fellowship from one of the tri-agencies in the three year period before or after their Banting application (referred to throughout this report as “Agency PDF”) and those without any Agency-specific postdoctoral fellowship (referred to as “Unfunded”).

Analysis of the Agency PDF and Unfunded applicants revealed that they were far from unsuccessful. Indeed after their unsuccessful Banting application, almost all secured alternative funding for postdoctoral training while a few obtained faculty tenure track positions. This has implications for any a priori expectations about the comparison of the two groups with the Banting fellows in relation to immediate and intermediate program outcomes. It seems to suggest that one should not expect much of a difference between successful and unsuccessful applicants in terms of their research productivity and other indicators and therefore if any difference is observed in favour of Banting fellows, it should be interpreted as giving even more credence to the effectiveness of the Banting postdoctoral fellowship.

Limitations

As with most evaluations, limitations were encountered during the data collection and are highlighted below. Further details about the methodology and limitations are presented in Appendix D.

- The bibliometric data presented in this evaluation are drawn from the Canadian Bibliometric Database (CBDTM) built by the Observatoire des sciences et des technologies (OST) using Thomson Reuters’ Web of Science (WoS). However, the bibliometric analyses presented in this report do not include all documents published by the studied researchers, since some works are disseminated through scientific media not indexed by the WoS (e.g., highly specialized journals, national journals, grey literature and particularly conference proceedings not published in journals). What these statistics do measure, however, is the share of researchers’ scientific output that is the most visible for Canadian and worldwide scientific communities, and therefore that is most likely to be cited.

- The WoS offers a good coverage of the publication output for the research fields of health sciences and natural sciences and engineering (NSE) including the content of international journals. By contrast, a large proportion of research results in the social sciences and humanities (SSH) is published in books and national journals not indexed in WoS and thus its coverage is far less complete for the social sciences, and even less so for humanities. While the results are therefore considered reliable for CIHR and NSERC applicants, they could not be considered to be representative of the publication outputs of applicants in the SSH domain. Therefore the bibliometrics findings for the SSHRC applicants are not presented in this report.

- The surveys of Banting fellows and unsuccessful applicants were administered at two different points in time: the Banting End of Award Report (BEAR) was completed by the Banting fellows between late 2012 and March 2015 while the unsuccessful applicant survey was administered from March 26, 2015 to April 20, 2015. Although most of the survey questions were taken from the BEAR, it is possible that respondents answered questions relating, for example, to research productivity, with reference to different time points: Banting fellows with reference to the two-year tenure of the Banting fellowship; and the unsuccessful, with reference to their postdoctoral training which could be longer than two years. As a result, only the bibliometric analyses results and not the survey results are used to compare the research productivity of Banting fellows, Agency PDF and Unfunded applicants.

- Although the initial invitations to host institutions targeted senior executives (e.g. Vice President or Vice-Provost) some chose to nominate alternatives with varying levels of involvement in the Banting program.

- The majority of Banting fellows’ supervisors who participated in the key informant interviews had only limited experience with the Banting program.

- The numbers of participants in the focus groups for unsuccessful applicants were small, fewer than four, limiting the data collected and potentially the diversity of perspectives.

2. Performance

2.1 Attracting and Selecting Top-Tier Candidates

Evaluation Question: Is the Banting program’s selection process able to attract and select top-tier postdoctoral candidates?

Key Findings

- The Banting PDF program is attracting and selecting top-tier candidates. The bibliometric analysis of the impact of publications showed that applicants in the health sciences and natural sciences and engineering domains, irrespective of success status had higher average of relative citation (ARC) scores and higher average of relative impact factor (ARIF) scores than the average for Canadian and world researchers. This evidence supports the view that the program is attracting some of the best researchers in the world.

- Selection committee members ranked Banting applications among the best they had reviewed in comparison to similar programs and strongly believed in the ability of the Banting PDF selection process to pick the best candidates.

- Senior representatives of host institutions and fellows’ supervisors considered Banting PDF applicants to be of a high quality describing them in such terms as “exceptional,” “outstanding” and “driven.”

- Half (52%) of successful applicants had also been successful in other postdoctoral fellowship competitions and had received offers for other fellowships.

- The program stipulates a 25% annual cap on awards held outside of Canada. Of the 283 fellowships awarded between 2010 and 2014, 125 (44%) were Canadians/permanent residents hosted in Canadian institutions, 71 (25%) were hosted abroad while 87 (31%) were foreign citizens who came to Canadian institutions. The cap has contributed to a net “inflow” or gain of 16 (87-71) fellows taking up the award in Canada with more international fellows hosted in Canadian institutions than Canadians/permanent residents hosted abroad.

- The cap highlights a tension within the program’s objective to attract and retain top-tier postdoctoral talent in Canada whereby the retention of top-tier postdoctoral talent in Canada limits the selection of the best applicants from among those who wish to hold their fellowship abroad. The cap has contributed to the net gain of 16 fellows taking up awards in Canada; however, it has resulted in some higher ranked applicants who intend to take-up the award abroad being passed over because the cap has been filled. During the period under review, 10 applicants (4%) were passed over as a result of the cap, with additional eight being passed over in the most recent (2014-15) competition. There is a lack of consensus regarding the need for the cap among supervisors, host institution representatives, federal agency representatives, and selection committee members with views split between not limiting the take up of the award internationally versus the need for a limit to retain postdoctoral fellows in Canada.

- There are signs of a decline in the proportion of foreign applications. After initially holding steady at 40%, the proportion of foreign applications fell to 34% in the last year under study, and further to 26% of applications in the most recent competition (2014-15). One possible explanation is that the requirement to demonstrate synergy between an applicant’s research program and the proposed host institution’s strategic priorities may be posing a barrier to foreign applicants.

In order to understand the ability of the Banting PDF program to attract and select the best candidates in terms of both research excellence and leadership, the evaluation assessed the research excellence of applicants in the three year period immediately preceding their Banting application and also canvassed expert opinion on the quality of applicants. Evidence from bibliometrics, the survey of Banting PDF selection committee members, key informant interviews with fellows’ supervisors and host institution representatives, and analyses of the BEAR data and program administrative data were used for this assessment.

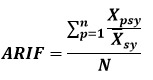

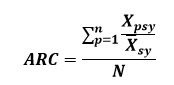

The bibliometric indicators used to assess research productivity were average annual number of papers, average of relative citations (ARC) and average of relative impact factors (ARIF). The average annual number of papers for a group of researchers refers to the total number of distinct publications assigned to that group divided by the number of researchers in the group and the number of years considered in the observation window.

The ARC relates to the number of citations received by a published paper over the period covered by the database following the publication year. An ARC value greater than 1 means that a paper or a group of papers scores higher than the world averageof its specialty; while a value below 1, shows that those publications are not cited as often as the world average.

The ARIF provides a measure of the scientific impact of the journals in which a group of researchers publishes. When the ARIF is greater than 1, it means that the group of researchers publishes in journals that are cited more often than the world average and when it is below 1, it implies that the group publishes in journals that are not cited as often as the world average. Further details about the definition and computation of the bibliometric indicators are presented in the Methodology Section (Appendix D).

Health Sciences

Findings from the bibliometric analysis for the health research domain reveal that candidates selected for the Banting fellowship were more productive in terms of the average annual number of peer reviewed publications in the three year period prior to applying for the Banting fellowship than those who were not selected (Table 2.1-1).Footnote 5 Also, the publications of the selected candidates had higher scientific impact in terms of the ARC than the Agency PDF (p<.05) and Unfunded (p<.001) applicants. Although there was no difference between the selected candidates and the Agency PDF applicants in relation to the ARIF scores, both groups published in journals with higher impact than the Unfunded applicants (Banting PDFs p<.01; Agency PDFs p<.05).

Both the ARC and ARIF scores also confirm that there was no significant difference in the quality of applicants over the years based on this measure as the scores were consistently well above the World average score of 1.0.| Banting PDF | Agency PDF | Unfunded | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Observatoire des sciences et des technologies (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) – Canadian Bibliometric Database current as of July 2014. | |||

| Average Number of Papers | |||

| 2010 | 1.70 | 1.40 | 0.92 |

| 2011 | 2.10 | 1.35 | 1.04 |

| 2012 | 1.48 | 1.36 | 1.00 |

| 2013 | 1.57 | 1.28 | 0.98 |

| 2010-2013 | 1.71 | 1.35 | 0.98 |

| Average of Relative Citations (ARC) | |||

| 2010 | 1.67 | 1.29 | 1.28 |

| 2011 | 2.26 | 1.49 | 1.19 |

| 2012 | 1.57 | 1.44 | 1.27 |

| 2013 | 1.54 | 1.36 | 1.42 |

| 2010-2013 | 1.79 | 1.37 | 1.28 |

| Average of Relative Impact Factors (ARIF) | |||

| 2010 | 1.52 | 1.30 | 1.24 |

| 2011 | 1.45 | 1.25 | 1.21 |

| 2012 | 1.36 | 1.33 | 1.33 |

| 2013 | 1.46 | 1.24 | 1.34 |

| 2010-2013 | 1.45 | 1.29 | 1.27 |

Natural Sciences and Engineering

The bibliometric analysis for the natural sciences and engineering (NSE) domain also showed that the selected candidates published more papers in the three year period leading to their application for a Banting PDF than the Agency PDF and Unfunded applicants (Table 2.1-2). Similarly, the selected candidates outperformed the Agency PDF (p<.05) and Unfunded (p<.01) applicants in terms of the impact of their publications as measured by their ARC scores. However, there were no statistically significant differences across the groups in terms of the impact of the journals in which they published as measured by the ARIF scores.

| Banting PDF | Agency PDF | Unfunded | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Observatoire des sciences et des technologies (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) – Canadian Bibliometric Database current as of July 2014. | |||

| Average Number of Papers | |||

| 2010 | 1.88 | 1.35 | 1.14 |

| 2011 | 1.90 | 1.06 | 1.18 |

| 2012 | 2.15 | 1.90 | 1.81 |

| 2013 | 2.31 | 2.38 | 1.91 |

| 2010-2013 | 2.06 | 1.70 | 1.43 |

| Average of Relative Citations (ARC) | |||

| 2010 | 2.36 | 1.55 | 1.51 |

| 2011 | 2.16 | 1.42 | 1.39 |

| 2012 | 2.14 | 1.66 | 1.66 |

| 2013 | 1.52 | 1.51 | 2.29 |

| 2010-2013 | 2.03 | 1.56 | 1.74 |

| Average of Relative Impact Factors (ARIF) | |||

| 2010 | 1.39 | 1.23 | 1.38 |

| 2011 | 1.42 | 1.08 | 1.26 |

| 2012 | 1.63 | 1.42 | 1.38 |

| 2013 | 1.24 | 1.20 | 1.39 |

| 2010-2013 | 1.42 | 1.27 | 1.36 |

It should be noted that the results for the 2013 cohort are not consistent with what we see in the findings for other years. The funded applicants for 2013 are slightly less productive than the Agency PDF applicants (2.31 against 2.38) and more surprisingly, their ARC and ARIF scores are lower than those of Unfunded applicants. It is unclear why this is so however, overall, across the four cohorts, it is clear that the selected candidates performed better.

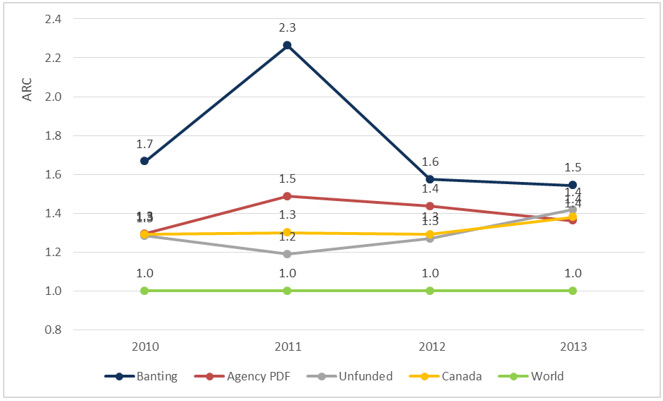

Beyond the differences between successful and unsuccessful candidates, the bibliometric analysis for the health sciences and natural sciences and engineering domains also indicate that the Banting program was attracting top-tier candidates. Their ARC scores irrespective of their funding status (except for Unfunded applicants in the health sciences domain) were higher than the ARC scores for Canadian and World researchers (Fig. 2.1-1).

Fig. 2.1-1: ARCs – Banting Applicants vs. Canadian and World Researchers in Health and NSE

Health

Figure 2.1-1 Health – long description

| ARC | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2010-2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banting | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.79 |

| Agency PDF | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.37 |

| Unfunded | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.28 |

| Canada | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | |

| World | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.00 |

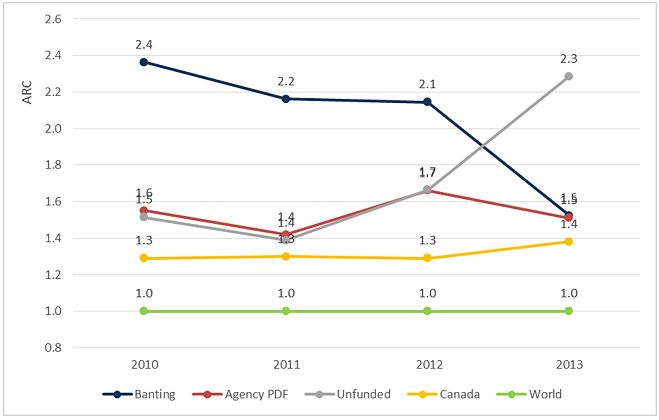

NSE

Figure 2.1-1 NSE – long description

| ARC | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banting | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| Agency PDF | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| Unfunded | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.3 |

| Canada | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| World | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Source: Observatoire des sciences et des technologies (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) – Canadian Bibliometric Database current as of July 2014.

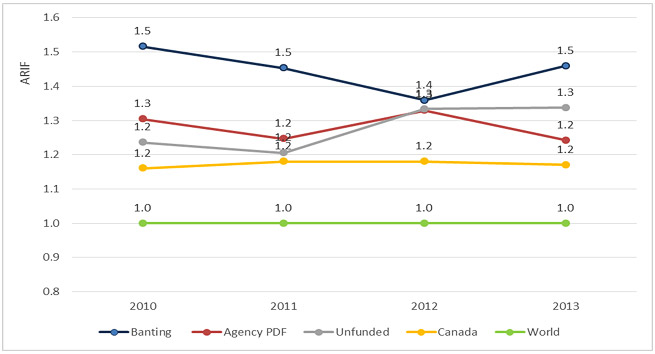

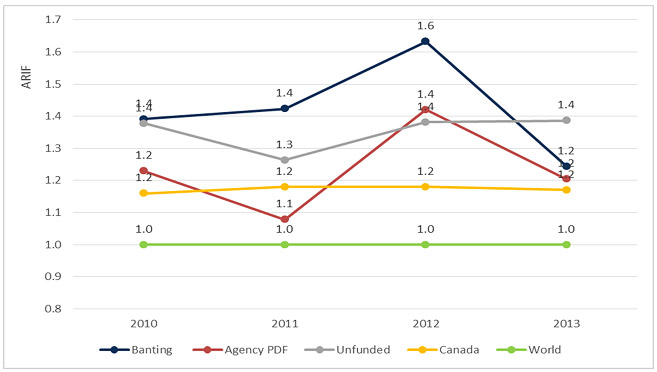

Second, the Banting applicants irrespective of funding status (except for 2011 with the Agency PDFs in the NSE domain) published in journals with higher impact (as measured by ARIF scores) than Canadian and World researchers (Fig. 2.1-2).

Fig. 2.1-2: ARIFs – Banting Applicants vs. Canadian and World Researchers in Health and NSE

Health

Figure 2.1-2 Health – long description

| ARIF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2010-2013 | |

| Banting | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.45 |

| Agency PDF | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.29 |

| Unfunded | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.27 |

| Canada | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| World | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.00 |

NSE

Figure 2.1-2 NSE – long description

| ARIF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

| Banting | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| Agency PDF | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Unfunded | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Canada | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| World | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

Source: Observatoire des sciences et des technologies (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) – Canadian Bibliometric Database current as of July 2014.

Findings from the key informant interviews showed that supervisors of Banting fellows and senior representatives in fellows’ host institutions considered Banting PDF applicants to be of a high quality, describing them in such terms as “exceptional,” “outstanding” and “driven.”

“He is absolutely exceptionally outstanding!”

“These are very highly dynamic, highly focused, highly successful, highly driven people who are aiming to be very successful and they're probably very driven around their research.”

Findings from analysis of the BEAR data corroborate the high quality of applicants. The findings showed that selected applicants are in very high demand:

- 52% (55/106) of former fellows (from the first two cohorts) who completed the BEAR had been offered other fellowships at time of notification of the Banting award.

- The fellowships were usually from CIHR, NSERC, SSHRC, the Ontario provincial government, voluntary organizations (e.g., Heart & Stroke Foundation) and international sources (e.g., US, Brazil and Japan).

- One had been offered a visiting assistant professorship at a US university and another had a fellowship from Harvard University.

- One-third (32%; 34/106) of responding former fellows left Banting before the full term. Of these, 88% (30/34) said they obtained another position with only 12% citing personal or other reasons.

Findings from the survey of Banting PDF selection committee members showed that over one-half (56%) of the members ranked Banting applicants in the top 10% and 86% ranked them in the top 20% of all fellowships they had reviewed in comparison to other programs. Also, when asked to assess the ability of the selection process to pick the best applicants, using a 7-point extent scale (where 1 meant “no extent” and 7 meant “great extent”), three-quarters (73%) of the selection committee members responded with a 6 or 7, confirming their strong belief in the efficacy of the Banting PDF selection process.

Attraction and Retention Versus 25% Cap on Training Outside Canada

The Banting program has a requirement that 25% of the 70 annual awards can be held outside Canada and this raises the potential that a better candidate could be skipped over if they proposed a foreign host institution and the 25% cap had been reached.

Analysis of program administrative data revealed that the proportion of applicants proposing to take the Banting fellowship to a foreign institution increased steadily from 16.4% in the 2010-11 competition year to 29% in 2013-14 (Table 2.1-3). Over the same period, the number of otherwise successful applicants who were passed over in favour of lower ranked applicants because of the cap ranged from zero in the first year to five in 2012-13. As a proportion of the 70 annual awards, the proportion of applicants passed over for the four year period being examined in this evaluation averaged 4%.

In the absence of any benchmark data, it is difficult to give an interpretation to the 4% except to say that 4% of the best and brightest top-tier candidates were not selected. It should be noted that eight applicants (or 11% of the 70 awards) were passed over in the most recent competition (2014-15, outside the scope of this evaluation). Thus it seems that the cap has resulted in a tension whereby the program’s objective to attract and retain top-tier postdoctoral talent in Canada is limiting the selection of the best applicants from among those who wish to hold their fellowship abroad.

| Canadian/Permanent Resident in Canada | Canadian/Permanent Resident Abroad | International Trainee in Canada | Annual Total | Applicants Skipped | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % (of 70) | |

| Source: Administrative data from Vanier-Banting Secretariat. | ||||||||||

| 2010-11 | 290 | 44.1% | 108 | 16.4% | 260 | 39.5% | 658 | 100% | 0 | 0.0 |

| 2011-12 | 196 | 39.1% | 107 | 21.4% | 198 | 39.5% | 501 | 100% | 2 | 2.7 |

| 2012-13 | 158 | 35.7% | 122 | 27.6% | 162 | 36.7% | 442 | 100% | 5 | 7.1 |

| 2013-14 | 159 | 36.7% | 126 | 29.0% | 149 | 34.3% | 434 | 100% | 3 | 4.3 |

| Total | 803 | 39.5% | 463 | 22.8% | 769 | 37.8% | 2035 | 100% | 10 | 3.5 |

The implications of the 25% cap can also be examined from the perspective of the number and proportion of Banting fellows who were foreign citizens and came to Canada versus Canadians and permanent residents who went abroad and those who remained in Canada for their training (Table 2.1-4). Of the 283 Banting fellowships awarded over the period 2010-2014, about one third of fellows (31% or 87) were foreign citizens who were hosted at an institution in Canada while one quarter (25% or 71), as stipulated by the cap, were Canadian citizens or permanent residents who travelled outside Canada for their training and about two-fifths (44% or 125) were also Canadian citizens or permanent residents who remained in Canada for their training. The difference of 16 (87-71) between international fellows hosted in Canadian institutions and Canadians and permanent residents hosted abroad could be interpreted as a net gain in terms of having fellows being physically present in Canada. However, it should be noted that there is no guarantee that the international fellows will remain in Canada or that Canadians abroad would return home after their postdoctoral training. For example, if it is assumed that the 10 higher ranked applicants who were passed over because of the cap (see Table 2.1-3) would have displaced 10 foreign citizens taking up the award in Canada, that would have led to a net outflow or loss (i.e. awards being taken up abroad) of 4 fellows,Footnote 7 a rather small number relative to the total of 283 fellows. It would be useful to monitor the numbers of Canadians/permanent residents taking up their Banting fellowship in Canadian institutions in relation to those going abroad as well as international fellows coming to Canada paying particular attention to longer term outcomes such as where they end up five and ten years after their training.

| Canadian/Permanent Resident in Canada | Canadian/Permanent Resident Abroad | International Trainee in Canada | Annual TotalFootnote 8 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Source: Administrative data from Vanier-Banting Secretariat. | ||||||||

| 2010-11 | 30 | 42.9% | 18 | 25.7% | 22 | 31.4% | 70 | 100% |

| 2011-12 | 31 | 42.5% | 18 | 24.7% | 24 | 32.9% | 73 | 100% |

| 2012-13 | 31 | 44.3% | 17 | 24.3% | 22 | 31.4% | 70 | 100% |

| 2013-14 | 33 | 47.1% | 18 | 25.7% | 19 | 27.1% | 70 | 100% |

| Total | 125 | 44.2% | 71 | 25.1% | 87 | 30.7% | 283 | 100% |

Opinions were split among key informant interview participants as to whether the 25% cap was necessary. The issue was not particularly salient among the key informants as it was not usually brought up spontaneously until prompted by the interviewer. Opinions were diverse including: removing the 25% cap and allowing the exchange of knowledge across international boundaries; restricting the fellowship only to Canadian host institutions; and deferring any action until the proportion of foreign-hosted Banting PDFs who eventually returned to Canada was known.

“International utilization is fundamental to academic research. All of us studied in other countries. We work with researchers in other countries, being international and certainly in today's global economy, the strongest researchers are part of international networks. And I think we should be doing everything we can to facilitate and see Canada as a player in those international networks. And I think we should open it up…. So let the high flier postdoc go with their money and go where they want to go.”

“That is a pipeline that is kind of open; but we are losing equal numbers of good people to other institutions in United States and elsewhere. So Banting has to really make it very clear that we will, if it’s retention, it’s attraction, we only allow postdocs coming into the country and working here - not allowing them to go overseas because they … then disappear. They will never come back.”

“But I'd want to know, for the people who do get it, what the percentages that come back are and if there's a good percentage that do come back, then it might be worth raising the 25% limit.”

Opinion among Banting selection committee members was also diverse. While 48% (25/52) of respondents to the survey were satisfied or very satisfied with the 25% cap, just over one-third (36%) were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. An additional 10% of the committee members were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied with the cap and 6% did not know.

Attracting Foreign Citizens Versus Canadians and Permanent Residents

Analysis of the Banting program application data shows that the proportion of foreign applicants was fairly steady for the first three years but fell to just over one-third in the last year under study (see Table 2.1-3), and declined further, to just over one quarter of applications (26%) in the most recent competition (2014-15). Also, the number of Canadians and permanent residents applying to the program fell for two years after program launch but has subsequently reached 564 in 2014-15, surpassing first-year levels.

The program is focused on attracting top class talent both nationally and internationally and therefore the recent decline in the proportion of applications from abroad may warrant further examination as other lines of evidence raise similar concerns.

There were indications from analysis of the key informant interviews that the program appeared to be too centered on Canada and might not be attracting enough international candidates.

“I think it's probably still kind of Canada-centric.”

“In terms of bringing in international researchers through the program, the results have been to my mind less than stellar…. Canadian professors are only going to nominate someone who they know. And they only know students and researchers with whom they have worked. So for an international researcher who may be crème de le crème of researchers, if they haven't had direct and ongoing relations with a Canadian professor, they can't even apply.”

The program requires the demonstration of synergy between an applicant’s research program and the strategic priorities of the proposed host institution. It is possible that international candidates with little or no connection to Canadian researchers or host institutions might be encountering problems developing such relationships which might put them at a disadvantage. Further examination of the factors underlying the decline in foreign applications might therefore be warranted.

Apart from attracting top talent, there were further indications from the qualitative analysis results that the Banting program was already being used to retain some of that top talent in academia although not necessarily only in Canada.Footnote 9 It was noted in the key informant interviews that host institutions were leveraging the Banting fellowship to retain high quality researchers who had already been attracted through the institutions’ other funding mechanisms.

“The candidate arrived without any scholarship right after finishing her doctorate in 2013, but she wasn't eligible to apply for the Banting because she hadn't received it in that fiscal year, something like that, and so, she was awarded the PBEEE [Programme de bourses d'excellence pour les étudiants étrangers - Merit Scholarship Program for Foreign Students], and then we applied for the Banting, so she was [already] here when we applied for the Banting.”

“Because I was aware of his talent, I had brought him to Canada with an exchange program for a year.”

2.2 Training and Support

Evaluation Question: To what extent have Banting fellows received appropriate training and support to carry out their research programs?

Key Findings

- Banting fellows, Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants rated their training environments very highly, including: quality of supervision and mentorship, research resources, and office space. This was consistent with the claims of supervisors and host institution representatives that they provided all postdoctoral trainees regardless of type of fellowship, with a wide range of training and mentorship opportunities.

- Banting fellows were more likely than Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants to report that they had received guidance and encouragement from their supervisors to pursue a research career, and that the postdoctoral experience had increased their desire to pursue such a career and improved their prospects of securing permanent employment.

- Banting fellows were accessing extra supports usually reflecting the institutional commitments that had been made at the application stage to support their candidature, including: seniority status in relation to other trainees; appointment into positions that allowed them to apply independently for grant funds; enrollment in faculty development programs and other customized professional development programs; extra research funds; office space, and conference travel.

- There was wide variation in the additional supports provided by host institutions such as being given the opportunity to independently apply for research grants or being paid a preferential rate for teaching and this variation could impact the ability of Banting fellows to conduct independent research.

Candidates apply for the Banting PDF in collaboration with their proposed host institutions who are expected to demonstrate synergy between their institutions’ priorities and the candidates’ proposed research. The institutions are also required to commit to providing the necessary training and support to the candidates to ensure a successful tenure. Surveys of applicants and key informant interviews with fellows’ supervisors and senior representatives of host institutions provided evidence on the extent to which the Banting fellows received appropriate training and support to carry out their research programs.

Research Environment

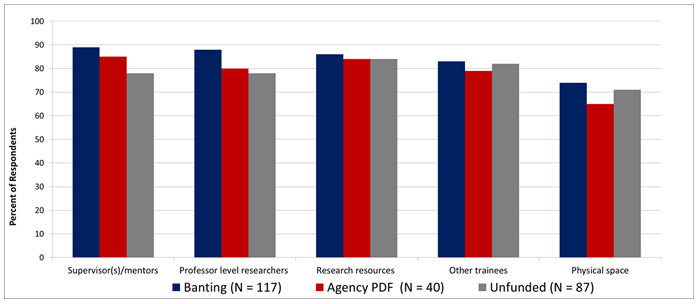

Survey findings showed that Banting fellows were just as likely as comparison groups to rate their research environment very highly (Fig. 2.2-1). The research environment included the quality of the supervisors, mentors, and other professor-level researchers with whom they worked and also the quality of other trainees such as colleague postdoctoral fellows, graduate, and undergraduate students. It also included research infrastructure and resources such as equipment, databases, and physical space, for example, building, laboratory, and office space. This finding is consistent with that of a nationwide survey of postdoctoral trainees that reflected a similarly favourable perception of the Canadian research environment (Mitchell et. al., 2013).

Fig 2.2-1: Percentage Reporting Research Environment to be Good or Excellent

Figure 2.2-1 – long description

| Banting (N = 117) |

Agency PDF (N = 40) |

Unfunded (N = 87) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervisor(s)/mentors | 89.00 | 85.00 | 78.00 |

| Professor level researchers | 88.00 | 80.00 | 78.00 |

| Research resources | 86.00 | 84.00 | 84.00 |

| Other trainees | 83.00 | 79.00 | 82.00 |

| Physical space | 74.00 | 65.00 | 71.00 |

Source: Survey of Banting Applicant 2015 and Banting End of Award Report 2010–2011 and 2011–2012.

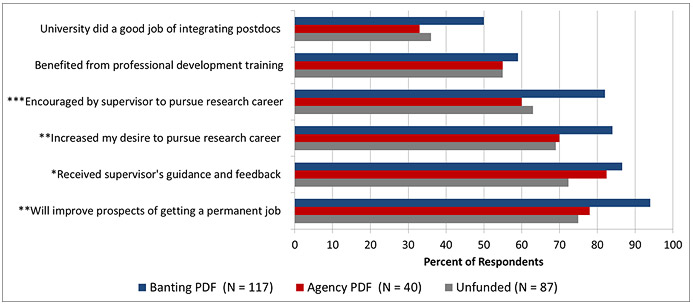

Support Received

The Banting PDFs were more likely than the Agency PDFs and the Unfunded applicants to report that the postdoctoral experience had increased their desire to pursue a research career, that it would improve their prospects of getting a permanent job, that they received guidance and feedback from their supervisor, and that they were encouraged by their supervisor to pursue a research career (Fig. 2.2-2). These differences were statistically significant.

Fig. 2.2-2: Support Received by Funding Status – Percent Saying Agree or Strongly Agree

Figure 2.2-2 – long description

| Unfunded (N = 87) |

Agency PDF (N = 40) |

Banting PDF (N = 117) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| **Will improve prospects of getting a permanent job | 75.00 | 78.00 | 94.00 |

| *Received supervisor's guidance and feedback | 72.400 | 82.500 | 86.600 |

| **Increased my desire to pursue research career | 69.00 | 70.00 | 84.00 |

| ***Encouraged by supervisor to pursue research career | 63.00 | 60.00 | 82.00 |

| Benefited from professional development training | 55.00 | 55.00 | 59.00 |

| University did a good job of integrating postdocs | 36.00 | 33.00 | 50.00 |

Source: Survey of Banting Applicant 2015 and Banting End of Award Report 2010–2011 and 2011–2012.

* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

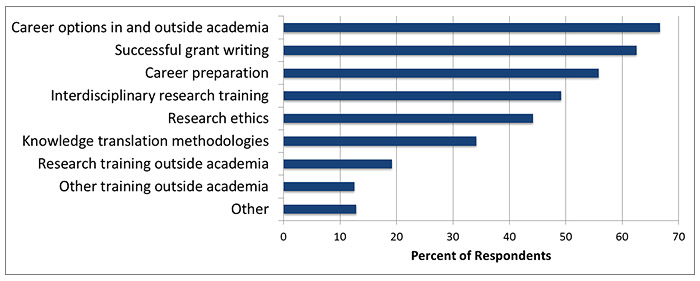

When presented with a list of types of training they had received, Banting fellows often selected receiving advice on career options within and outside academia, training in grant writing, and career preparation skills such as interview skills and preparing curriculum vitae (Fig.2.2-3). Only a few selected training outside academia such as industry, laboratory, policy, and patent law or business.

Fig. 2.2-3: Types of Training Received by Banting Fellows (%)

Figure 2.2-3 – long description

| Activities | Percent of Respondents |

|---|---|

| Other | 12.9 |

| Other training outside academia | 12.5 |

| Research training outside academia | 19.2 |

| Knowledge translation methodologies | 34.2 |

| Research ethics | 44.2 |

| Interdisciplinary research training | 49.2 |

| Career preparation | 55.8 |

| Successful grant writing | 62.5 |

| Career options in and outside academia | 66.7 |

Source: Banting End of Award Report 2010–2011 and 2011–2012.

Findings from the key informant interviews corroborated the support and training reported by the Banting fellows. Host institutions and supervisors provided Banting fellows with a wide range of training opportunities and mentorship (both formalized programs and informal) although these were usually the same as those provided to other graduate and postdoctoral trainees. The professional development opportunities included: grant writing, CV preparation, interview skills, negotiating job offers, supervising doctoral students and building a research group, effective collaborations and effective networking, knowledge translation and mobilization, communication skills, project management, intellectual property regulation, and entrepreneurship.

Some Banting fellows however, received additional opportunities and supports such as being appointed as adjunct professors which enabled them to apply independently for research funds like other faculty members, seniority status over other trainees at initial appointment, cash or in-kind support for research, enrollment in faculty development programs, and customized professional development programs. These supports were usually what the institutions had committed to in the candidate’s application.

“When the [application] form says what additional commitment, financial and otherwise, well we know it would be competitive, you ’ve got to step up.”

“And that's part of the actual application and that's highlighted in the institutional letter [of support].”

Analysis of the qualitative data on supports for Banting fellows suggests that there are some supports that are usually in place, others are sometimes in place and others are rarely in place. Some supports such as provision of office space, computers and access to library facilities appear to be taken as given. Professional development or training workshops were always provided to postdoctoral trainees, however, not all topics were necessarily available at one institution. At the same time, professional development programs specially customized for top-tier talent, for example, being enrolled in a faculty development initiative, appeared to be rare (Table 2.2-1).

| Type of Support | Usually in place | Sometimes in place | Rarely in place |

|---|---|---|---|

| NB: The checked symbol (✓) indicates availability of that type of support. | |||

| Dedicated office space /cubicle/Postdoctoral office | ✓ Basic space with desk and chair; sometimes shared with others |

✓ Bigger space, not shared |

|

| Computers | ✓ |

||

| Laboratory and other equipment | ✓ Trainees typically apply to a particular institution because certain facilities already exist there. |

✓ Extra equipment specific to fellow’s line of research –e.g., transcription equipment for qualitative researcher |

|

| Access to library | ✓ |

||

| Status/level of appointment | ✓ Regular postdoctoral trainee |

✓ Advanced trainee status; Adjunct professor, junior faculty or similar status with ability to apply independently for grant funds and manage own research account; Banting fellowship attached to tenure track position. |

|

| Research grant | ✓ Some funds may be available through institution-wide competition or from supervisor’s grant |

✓ Guaranteed amount per annum (e.g., $15,000) for duration of fellowship, to be used independently by fellow for their own research. |

|

| Publication grant | ✓ Funds to help with journal publication costs |

||

| Mentorship | ✓ Mentoring by supervisor; informal interactions with other experienced faculty. |

✓ Formalized, structured mentorship program; may not necessarily be with supervisor but other faculty mentor. |

✓ Formalized, structured mentorship program with specific requirements such as participating in selected workshops, having an individualized development plan. |

Networking opportunities |

✓ Occasional guest lectures, conference presentations |

✓ Presenting at formalized guest lecture series, e.g., Banting Fellowship Seminar Series; running an already established seminar series |

|

Conference travel |

✓ Postdoctoral travel awards, Institution-wide competition open to all postdoctoral trainees |

✓ Several conferences per annum |

|

Funds for travel to work or study tour of other laboratories |

✓ Stipend for travel to work in other laboratories |

||

Management skills and other such opportunities |

✓ Informal supervision and/or mentoring of students |

✓ Managing a laboratory, supervising doctoral students and other postdoctoral trainees, managing and reporting on status of laboratory account and budget |

|

Teaching opportunities |

✓ Access to teaching and learning centre or equivalent, teaching undergraduate classes |

✓ Graduate certificate program in university teaching; being paid at a preferential rate for teaching |

|

Professional development/training workshops |

✓ Available to all fellows although offerings may differ across institutions |

✓ Enrollment in customized professional development programs for top-tier talent, e.g., faculty development initiative |

|

Benefits package |

✓ Access to gymnasium/ fitness facilities; |

✓ Health/dental insurance especially for fellows in US; healthcare and other benefits are treated as separate payment in addition to Banting award; priority access to campus day care and social events. |

|

In a similar vein, while one Banting fellow was guaranteed a fixed amount for research for the duration of the fellowship, another received only a modest amount for travel while a third received nothing beyond the Banting stipend thus further confirming the variation in availability of training opportunities and supports across institutions.

“They gave me a pretty big research fund for each year, $15,000 each year to use as a research fund and for travel.”

“I received a little bit of travel mon

“For me, I don't have any money…So nothing else, not any other financial support or services or something in that manner.”

2.3 Demonstration of Research Excellence and Leadership

Evaluation Question: To what extent have Banting fellows demonstrated research excellence and leadership?

Key Findings

- Bibliometric analysis indicates that after receiving the award, Banting fellows in the health sciences and natural sciences and engineering had higher ARC and ARIF scores than their respective cohorts of Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants.

- Fellows’ supervisors and representatives of host institutions saw Banting fellows as strong research leaders and change agents.

- Banting fellows spent over two-thirds of their time on research and less on teaching, supervision, administrative tasks and other activities; these proportions were however, similar to those of Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants.

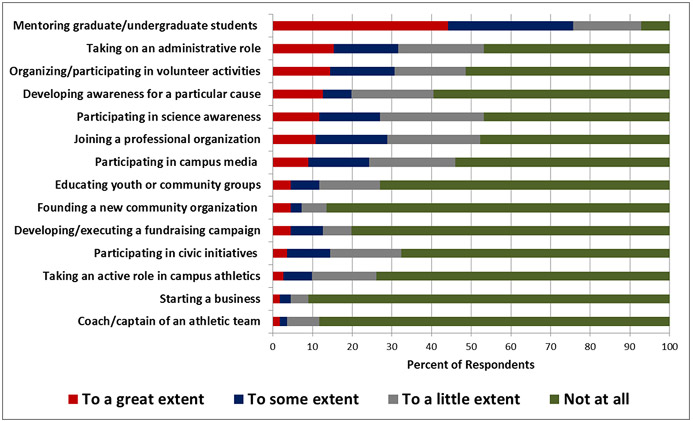

- Almost all Banting fellows, Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants believed that their research leadership abilities had developed to a great extent or some extent as a result of their postdoctoral training. However, only half of these three groups held a similar perception about the extent to which their teaching and service leadership abilities had developed during their training.

- As compared to research leadership development activities, Banting fellows were less likely to engage in teaching leadership development activities and least likely to engage in service leadership development activities.

A key expected outcome of the Banting fellowship is the demonstration of research excellence and leadership by fellows about two to four years after receiving their Banting PDF training. The first aspect of this outcome, the demonstration of research excellence, was assessed by examining Banting fellows’ research productivity and impact (as measured by bibliometrics) in the two to three year period following the award of the fellowship.Footnote 10 This was then triangulated with findings from key informant interviews with fellows’ supervisors and host institution representatives.

Research productivity was measured by the average annual number of papers produced by Banting fellows from the first two competitions and their corresponding cohort of unsuccessful applicants while research impact was measured by their ARC and ARIF scores. This use of only the first two competitions allowed for at least a two-year observation window for each cohort - publications of the 2010 applicants were examined for the years 2011, 2012, and 2013 while those of 2011 applicants were examined for 2012 and 2013. The bibliometrics method annualizes the data to account for variations in the widths of the observation windows.

Banting fellows’ demonstration of leadership was examined by assessing the proportion of time spent on research activities versus other activities such as teaching, supervision and administrative tasks. Other measures of demonstration of leadership were Banting fellows’ perceptions of the extent to which their leadership skills had developed as a result of the fellowship and the extent of their involvement in leadership development activities in the three domains of research, teaching and service.

Research Excellence: Health Sciences

The bibliometric analyses for the period following the award of the fellowship showed that in the health sciences domain, the Banting fellows produced on average, slightly more papers (1.6) than the Agency-PDFs (1.5) and 60% more than Unfunded applicants (1.0) (Table 2.3-1).Footnote 11 Also, the papers of Banting fellows were significantly more cited (ARC=2.46; p<.05) than those of Unfunded applicants (ARC=1.41). They were more cited than the Agency PDFs (2.01), but this difference was not statistically significant (Table 2.3-1).

The ARIF scores showed that the Banting fellows also published their papers in journals with higher impact (1.70) than Agency-PDFs (1.46, p<.01) and Unfunded applicants (1.26, p<.001) (Table 2.3-1). It should be noted however, that the higher overall ARIF score for the Banting fellows is largely due to the 2010 cohort since the analysis showed lower bibliometric indices for the Banting fellows in 2011. The results seem to suggest that two years may not be enough time to show a predictable trend in the ARC and ARIF indices in any particular direction and therefore caution needs to be exercised in interpreting the findings.

| Banting PDF | Agency PDF | Unfunded | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Observatoire des sciences et des technologies (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) – Canadian Bibliometric Database current as of July 2014. | |||

| Average Number of Papers | |||

| 2010 | 1.81 | 1.41 | 0.92 |

| 2011 | 1.44 | 1.56 | 1.02 |

| 2010-2011 | 1.64 | 1.46 | 0.97 |

| Average of Relative Citations (ARC) | |||

| 2010 | 3.06 | 2.03 | 1.26 |

| 2011 | 1.20 | 2.18 | 1.67 |

| 2010-2011 | 2.46 | 2.01 | 1.41 |

| Average of Relative Impact Factors (ARIF) | |||

| 2010 | 1.86 | 1.51 | 1.23 |

| 2011 | 1.36 | 1.37 | 1.32 |

| 2010-2011 | 1.70 | 1.46 | 1.26 |

Research Excellence: NSE

The bibliometrics findings for the natural sciences and engineering (NSE) applicants showed that the Banting fellows produced on average more papers (1.8) than the Agency-PDFs (1.5), and the Unfunded applicants (1.4) (Table 2.3-2). The findings also showed that the papers of Banting fellows were significantly more cited (ARC=2.19, p<.01) than those of Unfunded applicants (1.96). The ARIF scores showed that Banting PDFs published their papers in journals with similar impact (ARIF=1.34) as the Agency PDFs (1.33) and slightly higher impact than the Unfunded applicants (1.29) although these differences were not statistically significant (Table 2.3-2). As with the bibliometric results for the health sciences domain, the results for the NSE domain also need to be interpreted with caution due to the small number of data points.

| Banting PDF | Agency PDF | Unfunded | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Observatoire des sciences et des technologies (Thomson Reuters Web of Science) – Canadian Bibliometric Database current as of July 2014. | |||

| Average Number of Papers | |||

| 2010 | 1.72 | 1.41 | 1.50 |

| 2011 | 1.80 | 1.72 | 1.29 |

| 2010-2011 | 1.76 | 1.52 | 1.41 |

| Average of Relative Citations (ARC) | |||

| 2010 | 2.62 | 1.37 | 2.06 |

| 2011 | 1.60 | 3.71 | 1.73 |

| 2010-2011 | 2.19 | 2.13 | 1.96 |

| Average of Relative Impact Factors (ARIF) | |||

| 2010 | 1.33 | 1.24 | 1.31 |

| 2011 | 1.37 | 1.50 | 1.24 |

| 2010-2011 | 1.34 | 1.33 | 1.29 |

Overall, in the two to three year period after receiving the award, the Banting fellows in the health domain appeared to be showing higher levels of research productivity and impact than the Agency PDF and Unfunded applicants. Similarly, Banting fellows in the natural sciences and engineering domain appeared to be showing higher levels of research productivity than the Agency PDF and Unfunded applicants. They also appeared to be showing higher impact as measured by ARC scores than Unfunded applicants but they were broadly similar to the two comparator groups in terms of their ARIF scores. However, as has already been noted, the results for both the health and NSE domains need to be interpreted with caution as the only two data points in this time series do not show a predictable trend in the ARC and ARIF indices to warrant any definitive conclusions. These analyses should be revisited in future evaluations of the program at which point more data will become available.

Findings from the key informant interviews also confirmed the Banting fellows’ demonstration of research excellence. They were seen as exceptional individuals who had established strong research credentials through their publications.

“All our Bantings secured a tenure-track position… They were exceptional individuals.”

“We've got - I should think about two or three papers out now. The last one went viral ... We had a lot of media attention. So it was in the New York Times… and here locally; so all of that was great.”

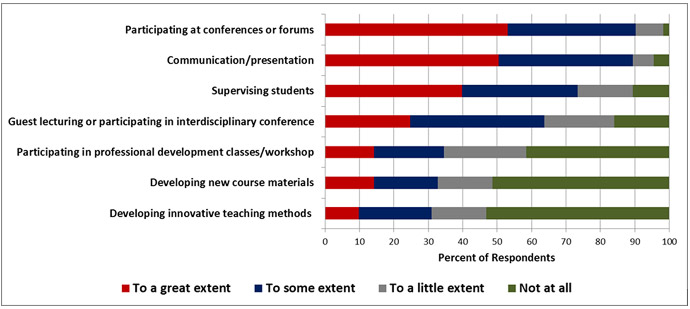

Demonstration of Leadership

The Banting program is aimed at developing the leadership potential of recipients in three domains - research, teaching and service - and positioning them for success as the research leaders of tomorrow. The demonstration of leadership was assessed for each of the three domains.

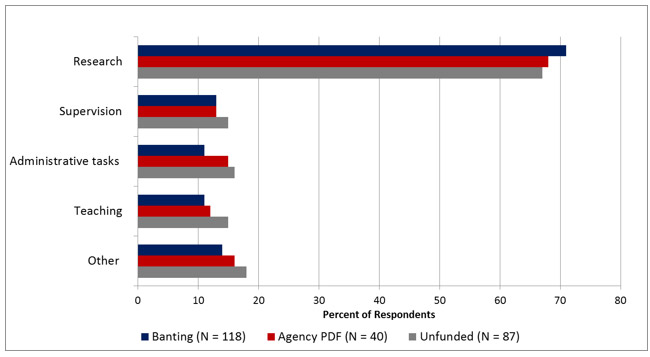

To assess the extent to which postdoctoral fellows were provided with support to develop their leadership skills, all survey respondents were asked about how much time they spent on research, teaching versus other tasks; the extent to which their research, teaching and service leadership skills had developed as a result of their postdoctoral training; and for the Banting fellows specifically, the extent of their involvement in leadership development activities in each of the three leadership domains. This was then triangulated with key informants’ perceptions of Banting fellows as demonstrators of excellence and leadership.

Broadly, the applicant survey and BEAR analysis findings showed no significant differences among Banting fellows, Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants in terms of time spent on various activities (Fig. 2.3-1). All respondents irrespective of funding status spent the largest proportion of their time, over two-thirds, on research activities and much less time on supervision, teaching and administrative tasks. However, the proportion of time spent on administrative activities by Banting fellows (11%) was found to be statistically different from those of Agency PDFs (15%) and Unfunded applicants (16%) (p<.05).

Fig. 2.3-1: Mean Percent Time Spent on Various Activities by Funding Status

Figure 2.3-1 – long description

| Unfunded (N = 87) | Agency PDF (N = 40) | Banting (N = 118) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Other | 18.00 | 16.00 | 14.00 |

| Teaching | 15.00 | 12.00 | 11.00 |

| Administrative tasks | 16.00 | 15.00 | 11.00 |

| Supervision | 15.00 | 13.00 | 13.00 |

| Research | 67.00 | 68.00 | 71.00 |

Source: Survey of Banting Applicants 2015 and Banting End of Award Report 2010–2011 and 2011–2012.

Perceptions of development of leadership abilities showed similar patterns as involvement in various activities, reflecting more emphasis on the research domain. Almost all Banting fellows, Agency PDFs and Unfunded applicants believed that their research leadership abilities had developed to some or a great extent as a result of the postdoctoral training (Fig. 2.3-2). In contrast, roughly one-half of each of the three groups indicated that their teaching and service leadership abilities had developed; Banting fellows were somewhat more likely to have identified teaching leadership (i.e., mentioned by almost two-thirds).

Fig. 2.3-2: Extent of Development of Leadership Abilities – Percent Responding to Some or Great Extent

Figure 2.3-2 – long description

| Q10 Overall Leadership at some or great extent | FundingStatus | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Banting | Agency PDF | Unfunded | |

| Research Leadership | 96.4 | 100 | 92.8 |

| Teaching Leadership | 64.2 | 47.4 | 50.6 |

| Service Leadership | 53.6 | 48.7 | 58.1 |

Source: Survey of Banting Applicants 2015 and Banting End of Award Report 2010–2011 and 2011–2012.

Note: Ns for research leadership: Unfunded - 83, Agency PDF - 36 and Banting fellows - 112; for teaching leadership, Ns are 85, 38 and 109 respectively; and for service leadership Ns are 86, 39 and 110 respectively.

Research Leadership

Apart from Banting fellows’ perceptions of their leadership abilities, findings from the key informant interviews and focus groups indicated that the fellows had strong skills in leadership in general and strong research leadership skills in particular. The Banting fellows were seen as candidates who had already established strong research leadership in their respective research fields and as change agents. The Banting fellows also saw the program as helping them to develop their leadership skills.

“We put in five [candidates] this year but two or three of them scored so high internally on leadership that we really see them as change agents. It's amazing what they've done in their short term.”

“Le programme Banting nous aide à recruter des gens qui ont déjà un leadership scientifique et qui ont déjà beaucoup de succès."

“There are several ways in which this program has already helped me build leadership or I guess a bit of leadership skills and to develop my career. [It] allowed me funding to move in at a relatively senior position in a lab that was even a relatively different area from what I have done in the past.”

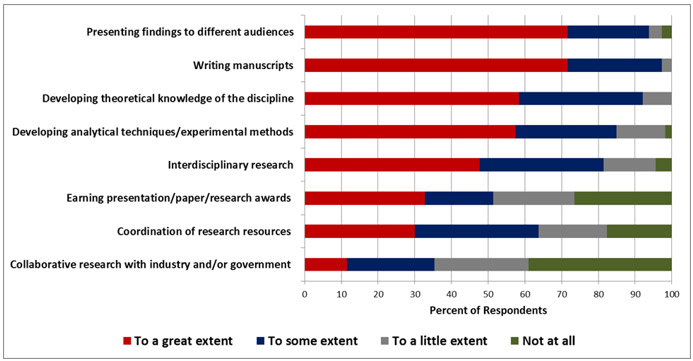

A majority of the Banting fellows were involved to a great extent in research leadership development activities; in particular, presenting findings to different audiences, writing manuscripts, developing theoretical knowledge of their discipline and developing analytical techniques and experimental methods (Fig. 2.3-3).

Fig. 2.3-3: Extent of Banting PDFs’ Involvement in Research Leadership Development Activities

Figure 2.3-3 – long description

| Collaborative research with industry and/or government | Coordination of research resources | Earning presentation/paper/research awards | Interdisciplinary research | Developing analytical techniques/experimental methods | Developing theoretical knowledge of the discipline | Writing manuscripts | Presenting findings to different audiences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To a great extent | 11.5 | 30.1 | 32.7 | 47.8 | 57.5 | 58.4 | 71.7 | 71.7 |

| To some extent | 23.9 | 33.6 | 18.6 | 33.6 | 27.4 | 33.6 | 25.7 | 22.1 |

| To a little extent | 25.7 | 18.6 | 22.1 | 14.2 | 13.3 | 8.0 | 2.7 | 3.5 |

| Not at all | 38.9 | 17.7 | 26.5 | 4.4 | 1.8 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.7 |

Source: Banting End of Award Report 2010–2011 and 2011–2012.

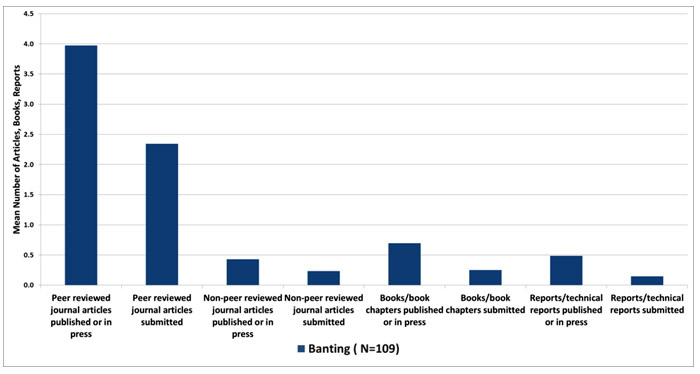

Banting fellows’ involvement in research leadership development activities was further corroborated by other data that confirmed that they were submitting articles and getting published in peer-reviewed and non-peer reviewed journals, writing books, book chapters, technical reports and other reports (Fig. 2.3-4).

Fig 2.3-4: Banting Fellows - Mean Number of Journal Articles, Books and Reports

Figure 2.3-4 – long description

| Peer reviewed journal articles published or in press | Peer reviewed journal articles submitted | Non-peer reviewed journal articles published or in press | Non-peer reviewed journal articles submitted | Books/book chapters published or in press | Books/book chapters submitted | Reports/technical reports published or in press | Reports/technical reports submitted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banting (N=109) | 4.0 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

Source: Banting End of Award Report 2010–2011 and 2011–2012.

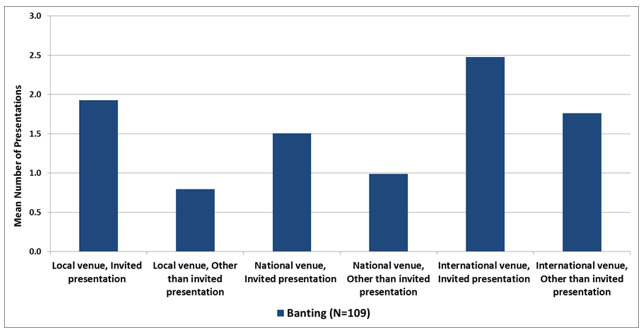

Additionally, Banting fellows were making invited presentations and other forms of presentations at local, national and international venues with invited presentations at international venues being the most common (Fig. 2.3-5).

Fig 2.3-5: Banting Fellows - Mean Number of Local, National and International Presentations

Figure 2.3-5 – long description

| Banting (N=109) | |

|---|---|

| Local venue, Invited presentation | 1.9 |

| Local venue, Other than invited presentation | 0.8 |

| National venue, Invited presentation | 1.5 |

| National venue, Other than invited presentation | 1.0 |

| International venue, Invited presentation | 2.5 |

| International venue, Other than invited presentation | 1.8 |

Source: Banting End of Award Report 2010–2011 and 2011–2012.

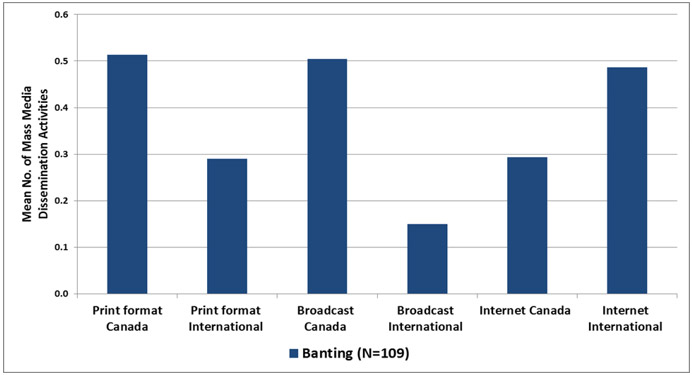

Banting fellows also engaged in knowledge dissemination activities through the Canadian print and broadcast media and the internet (Fig. 2.3-6).

Fig. 2.3-6: Banting Fellows - Mean Number of Mass Media Dissemination Activities

Figure 2.3-6 – long description

| Banting (N=109) | |

|---|---|

| Print format Canada | 0.5 |

| Print format International | 0.3 |

| Broadcast Canada | 0.5 |

| Broadcast International | 0.1 |

| Internet Canada | 0.3 |

| Internet International | 0.5 |

Source: Banting End of Award Report 2010–2011 and 2011–2012.

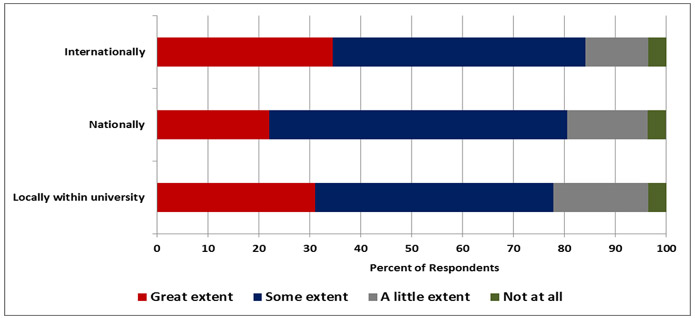

When asked about the extent of influence of their research, over three-quarters of the Banting fellows expressed the belief that their research had influence to some extent or a great extent at each of three levels - locally within the university, nationally and internationally (Fig. 2.3-7).

Fig. 2.3-7: Percent of Banting PDFs Reporting Research Influence at Local, National and International Levels

Figure 2.3-7 – long description

| Great extent | Some extent | A little extent | Not at all | |

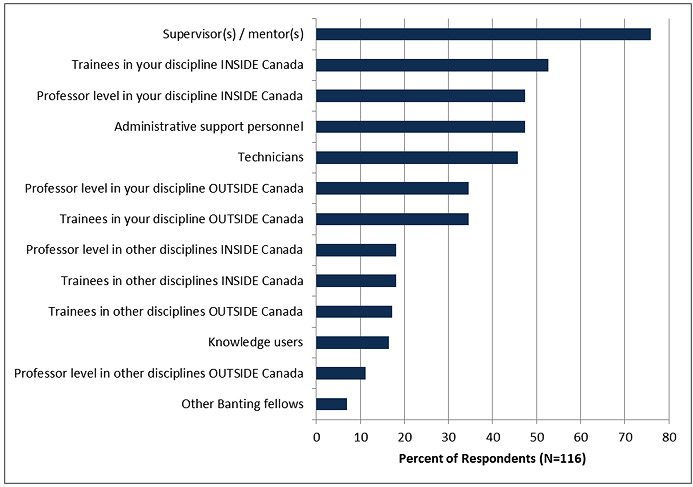

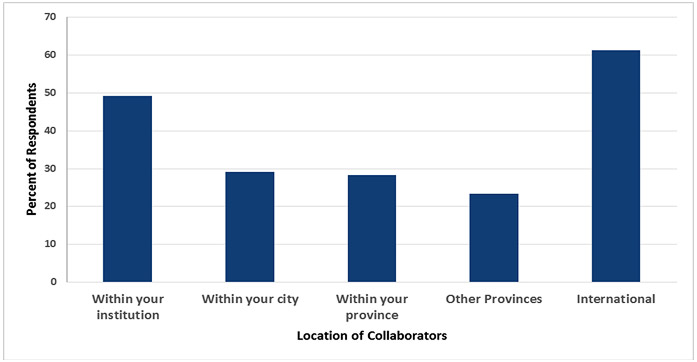

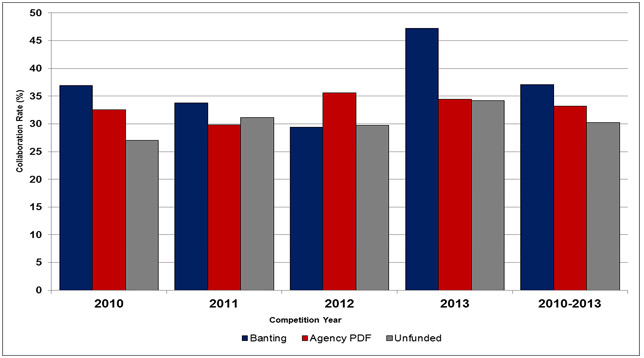

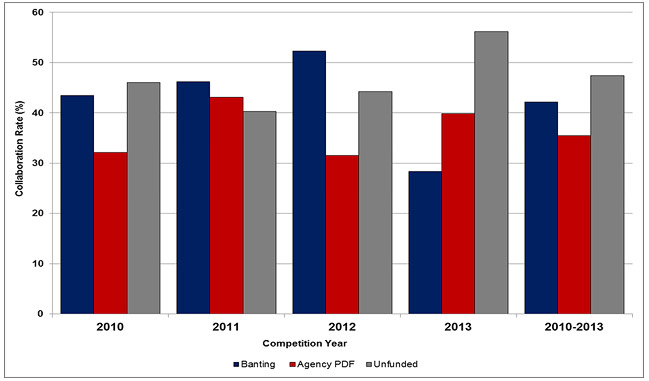

|---|---|---|---|---|