Best Brains Exchange Report

Innovative approaches and pathways used to integrate home and community care with primary health care for elderly persons in rural Canada

Hosted by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research in collaboration with Health Canada

CIHR boardroom

160 Elgin Street

Ottawa, Ontario

November 28, 2017

This report was prepared for Health Canada. The content of this document reflects the presentation materials and discussions held by participants at the November 28, 2017 Best Brains Exchange. It does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Health Canada or the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Background

- Welcome and opening remarks

- Scene setting: Portrait of rural Aging in Canada

- Innovative approaches and pathways: Integrating primary health care for older persons in rural canada and beyond

- Care innovations for older persons across rural canada

- Challenges and opportunities to integrating community care for older adults in rural communities

- Guided discussion: Building an inventory of examples

- Guided discussion: Making the innovations stick

- Closing remarks

- References

1. Executive Summary

Currently, there are many practical and cost-effective solutions to help rural elderly residents remain in their homes and communities longer and stay out of long-term or acute care facilities. Some of these innovative approaches and practices can be drawn from the community; some from various levels of governments or the healthcare sector; and others from the non-profit or for-profit sectors.

Given the existing stock of promising approaches, it is important to first learn from what currently exists rather than reinventing the wheel when seeking potential solutions. Practices and approaches that have proven effective in one rural community can often be adapted and scaled up in other rural communities – assuming the unique needs of each community and its residents are explicitly taken into account.

That is why on November 28, 2017, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, in collaboration with Health Canada, brought together key experts and stakeholders in a Best Brains Exchange (BBE) format. The purpose of this BBE was to identify what works, and why, when it comes to integrating home and community care with primary health care for older persons in rural areas.

Key takeaways from the BBE event include:

- Local context matters: The first step in developing and implementing programs that work is to communicate and consult with local communities, including seniors, family members and caregivers. Communities need to be empowered to identify their own diverse needs and supports as well as the unique needs and characteristics of their older residents. A one-size-fits-all approach rarely works. Services need to be flexible, focus on the needs of individual seniors and their caregivers, and cut across care settings. This may include:

- Engaging local champions to integrate home and community care

- Recruiting and training personal support workers (PSWs) from the community

- Leveraging a community's existing assets (e.g., local businesses, service clubs, municipal services, charities, faith organizations)

- Integrating formal and informal support services, including family physicians and the community health work force

- Equipping local health providers with the tools and training to identify high-risk seniors early (as well as the needs of their family caregivers)

- Expanding the community care team beyond traditional healthcare providers to include social service professionals, community volunteers and family members

- Health rather than healthcare: Globally, the paradigm is shifting from a focus on healthcare to a focus on health. In addition to healthcare, this involves addressing an individual's functional challenges which are often related to non-healthcare assets like housing, transportation and social connectedness. The most successful solutions to these challenges often come from communities, in partnership with local health authorities, non-governmental organizations and other stakeholders.

- Broadly defining "home": Enabling frail seniors to "live in place" could mean their primary residences or within their community (i.e., single family home, assisted living or other supportive housing).

- The role of federal, provincial and territorial governments is strategic: There was broad agreement on the need for governments to develop a framework or clear statement on what type of society we want for our older citizens. The statement should include equity and access as key goals. There is also a role for government to incent change through laws, regulations, funding and other supportive measures that promote health promotion and prevention.

- Better utilizing underutilized professionals: More jurisdictions are widening the scope of practice for "mid-range" professionals such as nurses, paramedics, pharmacists and other providers like community health workers to respond to access issues in rural areas. Paramedics are increasingly being recognized as a 24-7 community resource that can provide enhanced primary, emergency and preventative care, particularly in rural areas.

- Training and supporting informal caregivers and volunteers: Recognize, reward, support and incentivize volunteers and informal caregivers, including family, friends and neighbours.

- Valuing the role of Personal Support Workers: To improve recruitment and retention, there needs to be greater recognition and support, as well as better compensation and a clearer career pathway for PSWs.

- Technology: This can be a platform on which to leverage a team of health professionals. Leveraging technology can be as simple as a reassurance phone call, or as complex as a home equipped with bio-metric sensors.

- Proving what works: Using implementation science frameworks (e.g., Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research) when evaluating and implementing innovative interventions helps uncover critical factors that affect implementation at multiple levels.

- Sharing what works: A national catalogue of successful innovations for rural elderly would help communities and other stakeholders identify proven or promising solutions.

- Addressing research gaps:

- Informal caregivers and support networks are the least researched human resource category when it comes to caring for older seniors

- Community-driven research, supported by a network of researchers, to evaluate promising local innovations

- More evidence on the issues facing older seniors in rural areas

- Community-level data and robust implementation research

- A national rural research agenda and research evaluation frameworks

- Bolstering data holdings and the evaluation of interventions will be critical

- Expanding and tracking community paramedicine

- More funding for interdisciplinary research

- A national rural strategy: Such a strategy could address the unique differences of rural areas and align with funding and community priorities.

2. Background

About Best Brains Exchange (BBE)

Best Brain Exchanges are one-day, in-camera meetings for decision makers and researchers with expertise on a topic that has been identified as a high priority by provincial and territorial (P/T) ministries of health and the federal Health Portfolio.

The objectives of the BBE program are to:

- Provide the ministry / Health Portfolio with an overview of the latest evidence from researchers on the basis of their expertise and knowledge on critical issues related to the ministry/ Health Portfolio identified topic;

- Improve participants' knowledge of and access to research evidence in the topic area; to address the issue(s) that the ministry / Health Portfolio is or will be facing;

- Facilitate roundtable discussions that engage stakeholders, researchers and decision makers; and

- Enable the ministry / Health Portfolio to consult with stakeholders and researchers for their knowledge and perspectives on particular questions.

Policy context

Rural communities for this report are defined as locations with a core population of less than 10,000 people and where less than 50% of the population commutes to larger urban centres for work. Canadians living in these communities face differences in health care access, health risk factors, and social determinants of health compared to their urban counterparts. Local health care services and access to safe and good quality care are often limited, with fewer health care providers living and working in rural communities. In particular, these challenges may affect those aged 65 years and over, who may not be able to travel to access needed services. Health risk factors, such as being overweight and smoking, are more prevalent in rural areas and this population also faces a higher incidence of some chronic diseases, injury, and mortality.Footnote 1, Footnote 2 Incomes in rural regions are demonstrably lower than those in urban regions.Footnote 3

Health Canada's 2017-18 Departmental PlanFootnote 4 identifies support for health system innovation and models of care as a priority. A key initiative of this is the establishment of multi-year health agreements with provinces and territories with a focus on improving home care, among other areas.

Furthermore, Health Canada is committed to ensuring sound science and advancing gender equality through the use of sex and gender based analysis (SGBA). The Health Portfolio's policy approach requires that SGBA be used in the development, implementation and evaluation of our research, legislation, policies, programs and services to address the different needs of women, men, girls, boys and gender diverse individuals, as appropriate. Given that health workforce demographics, informal caregiving, and chronic disease burden have a gender component, SGBA is an important consideration.

Identified need for evidence

The anticipated outcome of the BBE will help inform the development of an inventory of examples of practical, cost-effective, timely, and forward-looking approaches that jurisdictions could implement to respond to their health system needs. P/T representatives, health system implementers, and key decision makers were engaged at the BBE table. Evidence discussed at the BBE will be shared with P/Ts via the Federal/Provincial/Territorial (F/P/T) Committee on Health Workforce to inform jurisdictional health human resource delivery, planning and management.

The BBE discussion and research findings aligned well with the Common Statement of Principles for Shared Health Priorities (CSOP) endorsed by F/P/T governments aimed at strengthening the health care system. As Canada's population ages and chronic disease rates increase, Canadians will need access to more health care services outside the traditional settings of physicians' offices and hospitals. Across Canada, all jurisdictions are putting in place new approaches to enhance access to vital health care and support services at home and in the community, and reduce reliance on more expensive hospital infrastructure. Aligned with the CSOP, significant federal investments over 10 years will target improved access to appropriate services and supports in the home and the community.

Building the knowledge base of innovative approaches to integrating home and community care with primary health care for older persons in rural settings is expected to complement existing efforts to broaden rural health care delivery and allow for a more team-based approach. For example, in February 2017, the College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada held a Rural Health Care Summit where national, provincial and regional policy-makers, researchers, and practitioners endorsed a Rural Road Map for ActionFootnote 5 to ensure that Canadians living in rural communities have equitable access to primary health care. The report identified the need to establish practice models to provide rural communities with health care responsive to their needs, and the importance of a national rural research agenda to support rural workforce planning aimed at improving access to patient-centred and quality-focused care. Knowledge shared at the BBE will contribute to furthering these efforts.

Objective of Meeting

As part of its commitment to helping Canadians maintain and improve their health, the Government of Canada is working to ensure that Canadians living in rural communities have equitable access to health care services. The November 28, 2017 BBE focused on sharing research and implementation evidence to create an inventory of examples of practical, cost-effective and innovative approaches that could be implemented over the next 10-15 years.

The BBE focussed on the following policy questions:

- What promising practices and activities exist that integrate home and community care with primary health care for elderly persons in rural Canada?

- What are the key characteristics of these activities and promising practices that enable rural seniors to stay in their homes longer?

- What are the critical lessons learned, including elements of success and common pitfalls, for integrating primary health care with home care and community care for seniors living in rural communities?

Meeting Participants

The BBE event reached capacity, with nearly 30 participants from across Canada attending the BBE in Ottawa, including representatives from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Health Canada, provincial and territorial health ministries, regional health authorities, the community services sector, health associations, the volunteer/charity sector, care delivery organizations, the health technology sector, nursing and physician groups, academics, emergency services, and elder care organizations.

Outline of Meeting

The agenda for the meeting and speaker and facilitator biographies are provided in Appendix 1 and 2 of this report.

Key topics were addressed in four presentations:

- Scene setting presentation – Portrait of rural aging in Canada: Janice Keefe, Professor and Director, Nova Scotia Centre on Aging, Mount Saint Vincent University

- Innovative approaches and pathways: Integrating primary health care for older persons in rural Canada and beyond: Paul Williams, Professor, Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto

- Care innovations for older persons across rural Canada: Samir Sinha, Director of Geriatrics, Sinai Health System, and Associate Professor, Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto

- Challenges and opportunities to integrating community care for older adults in rural communities: Grace Warner, Associate Professor, School of Occupational Therapy, School of Nursing, Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, Dalhousie University

A short question-and-answer period followed each presentation. Speakers and participants engaged in guided discussions, and open dialogue among participants followed the Chatham House Rule.

3. Welcome and Opening Remarks

Co-chair and Facilitator: Yves Joanette, Scientific Director, Institute of Aging, Canadian Institutes of Health Research

Co-chair: Helen McElroy, Director General, Health Care Programs and Policy Directorate, Health Canada

Ms. McElroy and Dr. Joanette welcomed participants to the BBE meeting and thanked participants for coming to share their knowledge and experience on a topic that is important to many Canadians.

Enabling the frail elderly to age in place is a challenge in both urban and rural areas, but it can be particularly difficult in rural areas where care and supports may be limited or unavailable. As Ms. McElroy explained, the goal of the BBE is to identify examples of innovative approaches and pathways that are practical, cost-effective, timely and forward-looking, as well as identify approaches and levers that jurisdictions can put in place to increase the chances of a solution being successfully implemented.

For Health Canada, this BBE provides an opportunity to facilitate knowledge, exchange and dialogue to support P/T decision makers, researchers and stakeholders in their efforts to improve delivery of health care. It will be important for governments, academics and other stakeholders to work collaboratively to bring about the system changes needed to better integrate home and community care with primary health care for elderly persons in Canada.

Dr. Joanette noted that the goal of this BBE was not necessarily to "reinvent the wheel" and come up with new and untested innovations. Rather, the goal was to identify proven or promising approaches and practices that allow people to live in their rural homes and communities, and to identify areas where further research is needed.

Indigenous rural communities

Dr. Joanette noted that to keep the scope of the BBE manageable, it was decided for the purposes of this meeting to not focus on any specific population, such as elderly Indigenous people living in rural areas. Both Health Canada and CIHR recognize there are pronounced disparities in health and access to care for Indigenous people in rural Canada. Dr. Joanette added that CIHR and all of its institute directors are committed to improving the health of Indigenous people, and are very much inspired by many of the values of Indigenous culture, including its respectful attitudes to elders.

4. Scene Setting: Portrait of Rural Aging In Canada

Janice Keefe, Professor and Director, Nova Scotia Centre on Aging, Mount Saint Vincent University

Reality 1: Provinces differ in proportion of rural and aging

Looking at only national-level population statistics will not provide a complete or necessarily accurate picture of rural older Canadians or the communities in which they live. For example, some rural communitiesFootnote 6 have a high percentage of older adults because seniors have moved there for their retirement. Other rural communities have a high percentage of older adults who have lived there their entire lives and thus have stronger family and social connections. Others still may have a high proportion of older people because working-age residents have left to seek education and employment. This may limit the availability of family support as family will be living at a distance.

While each rural community is unique in its own way, the majority do share a common demographic challenge: their overall populations of rural residents are shrinking as a proportion of the provincial total as more young people leave for jobs and education (this trend is slower in Atlantic Canada). As a result rural populations are aging more quickly than urban populations.

Some demographic highlights:

- A growing 75+ cohort: The number of people over 75 is projected to increase across all provinces between 2016 and 2020.

- Atlantic Canada bucks the national trend:

- The region has proportionally more people over the age of 75 than other provinces.

- Rural populations are holding steady in Nova Scotia (40-45%) and NL (40%), compared to about a 20% drop among rural populations nationally.

- NL has gone from having the youngest median age in Canada (from the 1970s) to having the oldest median age in 2010 and 2015.

- The young face of Alberta: The youngest median age in Canada is now in Alberta. Rural Alberta also has a younger median age than rural areas in other provinces.

- Rural women still the majority: On average, there are more women aged 65+ in rural areas than men aged 65+.

Reality 2: There are many "rurals"

Understanding the needs and characteristics of older rural residents, and the challenges and opportunities they and their communities face, is essential to understanding what supports are needed to help them live at home longer.

Often people's assumptions about rural living do not reflect the reality. Two commonly held and competing views are that are: rural communities are isolated and lack formal services; or rural communities are warm and friendly places where older people have access to supports and resources.

However, these assumptions are not necessarily based on evidence. Dr. Keefe's research identified three key characteristics that differentiate community supportiveness:

- Population size (i.e., small rural communities have higher community supportiveness)

- Proportion of long-term residents (i.e., a higher proportion of long-term residents is associated with higher community supportiveness)

- Proportion of seniors (i.e., a higher proportion of seniors is associated with higher community supportiveness)

Rural case studies have found that seniors' ability to fulfil their needs depends on physical, social and economic resources as well as access to information.

| Physical locality | Social aspects |

|---|---|

| Size of population | Proportion of seniors |

| Distance from urban centre | # of females |

| Resources for continuing care services | Household income |

| Climate change (e.g. rising sea levels and impact on local infrastructure in coastal communities) | Part-time/part-year employment |

| Long-term residents |

Dr. Keefe's presentation highlighted that decision makers should avoid implementing a one-size solution for all rural communities. Each community's unique needs and physical and social characteristics should be identified before developing or implementing a support or intervention.

Reality 3: Older people within rural communities are diverse

Intensive focus group research in three rural communities in Alberta, Nova Scotia and Ontario found very different types of people within each community. Different groups of seniors have different needs and their ability to fulfil those needs depends on their physical, social and economic resources as well as access to information:

- Active seniors:

- These people are the backbone of the community. They have typically lived in the community a long time and often hold positions of leadership in community organizations, service clubs, churches, charities and municipal councils.

- Stoic seniors:

- These people are described as proud, private, independent, often isolated and reluctant to seek assistance from services and supports.

- Vulnerable seniors:

- These individuals tend to be frail, lower income, more disconnected and with limited access to social supports and services. Even if private support services are available, these seniors often don't have the financial means to purchase them.

- Frail seniors:

- This group is usually isolated, needs support and often has multiple chronic health issues.

- Having a history with the community helps:

- Frail seniors fare better in communities where they have lived longer. There are usually more family and social supports available than in rural retirement communities where residents may have moved there from other regions.

- Program implications:

- When developing programs or interventions it is important to respond to the diverse needs of rural seniors and their communities.

Closing Question: Do rural elderly have to move to receive good care?

The short answer is "no". It is possible to provide good care in rural areas while also enabling seniors to stay in their homes longer, assuming certain supports are available. A 2007 guide to Age-Friendly Rural and Remote Communities [ PDF (344 KB) - external link ] prepared for F/P/T Ministers responsible for seniors identified several age-friendly features and barriers, including five practical steps for building an age-friendly community: form an age-friendly committee/team; evaluate the age-friendliness of the community; develop a plan; put the plan into action; and monitor progress by having clear and measurable goals and targets.

Access to family and friends: Having access to family, friends and neighbours – the people you know and trust – has been one of the biggest factors that have allowed older people to live in their homes longer. One of the biggest supports they provide is transportation. However, these traditional caregivers are growing old themselves and many of the younger generation are moving away.

Access to health services: This includes non-medical services such as home maintenance and transportation (e.g., prompt snow removal for older adults or access to volunteer drivers) and the ability to "age in place" or in their community (with access to medical and personal care and support for activities of daily living). More recently, innovative approaches to providing health care services have included expanding traditional scopes of practice of health providers (e.g. using community paramedics to conduct home visits), which improves access to routine healthcare services to underserved populations.

Conclusions/Next Steps

The first step in developing and implementing programs that work is to understand the diverse needs and supports within each rural community. A "one-size-fit-all" approach rarely works. Instead, look at implementing services and supports that are flexible, focus on the elderly and their caregivers, and cut across home, continuing and acute care.

5. Innovative Approaches and Pathways: Integrating Primary Health Care for Older Persons in Rural Canada and Beyond

A. Paul Williams, Professor, Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto

Dr. Williams approached his research with a simple idea: If we pay as a society to keep older persons in hospitals and long-term care facilities, why wouldn't we pay to keep them in their homes when that is an option?

It's a question Dr. Williams and his interdisciplinary research team has been asking communities across Ontario: "How would you put together the services, resources and people who are in your community to keep people at home if that's where they want to be?"

The shift from health care to health

Society's view of health and healthcare is changing. Community consultations in Ontario, as well as experience in countries like Japan, reveal that people and policy-makers are talking more about health (what it takes to keep older persons healthy and independent for as long as possible), and less about traditional healthcare (i.e., hospitals and doctors). Healthcare is viewed as but one influence that helps to keep people healthy and fit in older age.

In Canada, primary care is often defined narrowly in terms of first contact with the formal medical system. In comparison, the World Health Organization (WHO) goes beyond a "narrow offer of specialized curative care" to embrace a "broad whole-of-society approach" that focuses on health promotion, prevention and the social determinants of health:

"Doing so would meet several objectives: better health, less disease, greater equity, and vast improvements in the performance of health systems. Today, health systems, even in the most developed countries, are falling short of these objectives."

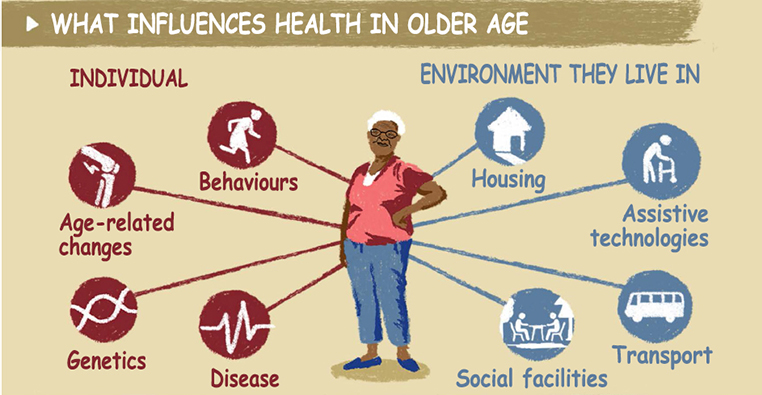

Healthcare is only one of several key determinants of healthy aging. According to the WHO, other important factors include diet, exercise, behaviours, genetics and disease, and environmental factors such as housing, transportation, assistive technologies and social facilities.Footnote 7 There is a growing body of evidence showing that focusing on health, and not just healthcare, reduces primary care costs while enabling seniors to live in their homes and communities longer.

What influences health in older age

Figure long description

Individual

- Behaviours

- Age-related changes

- Genetics

- Disease

Environment they live in

- Housing

- Assistive technologies

- Transport

- Social facilities

Adapted with permission from World Health Organization, Healthy Aging, 2015; April 2018

An aging society is not just about older persons

Canada's changing demographics are making it more difficult for people to stay in their homes and communities longer.

Canada's demographic trends are well known. Its proportion of older adults is growing at a much faster rate than people being born to replace them. This is particularly pronounced in the 85+ group which increased nearly 110% between 1983 and 2013 according to Statistics Canada. In 2016, the number of people between 0 and 14 is now – for the first time – less than the number of people 65 and older. Canadians are living longer. The older we get, however, the more likely we are to develop functional challenges. More seniors and fewer younger people translates into more potential care recipients and fewer potential care providers, respectively.

The government has responded by embracing a proactive immigration strategy, which has increased the country's diversity, making it a model for other nations around the world.

Aging also occurs unevenly, with some regions aging faster. The data show some provinces aging more rapidly than others, notably Atlantic Canada, but this trend is also seen in rural areas such as Northern Ontario and across the developed world, including in Japan.

Informal caregivers and support networks are crucial

Canada's changing demographics are making it more difficult for people to stay in their homes and communities longer. Rural areas in particular rely on families and informal carers and support networks more than formal services to care for older adults in the community. While informal caregivers are sometimes seen as a vast pool of free labour, they are better viewed as the invaluable backbone of the sector, which itself requires consideration and support. Many of these informal caregivers are seniors themselves who will face their own functional challenges as they age.

Despite the recognized importance of informal caregivers, they remain the least researched human resource category when it comes to caring for older seniors.

A 2014 report by the Institute for Public Policy Research in the United Kingdom (UK) recognized that the UK's growing family care gap would mean that by 2017 the number of seniors in need of care would outstrip the number of family members able to provide that careFootnote 8. The report's authors said the UK's plan should be to ‘build' and ‘adapt': "to build new community institutions capable of sustaining us through the changes ahead and to adapt the social structures already in place, such as family caring, public services, workplaces and neighbourhoods. This will require a different role for the state, one that is more about establishing partnerships with families and communities than traditional service delivery."

Japan and Germany have responded to this demographic challenge by implementing a "long-term care system". In Canada, we think of "long term care" as a particular, institutional site of care. In Japan and Germany, for example, policymakers think of "care over the longer term," which can be provided in many different sites including people's own homes or in residential beds; this leads to broader system strategies which can span a range of community-based and institutional settings.

Building supportive communities

Dr. Williams highlighted several models of supportive communities that are helping seniors age in place. A common ingredient among all is their focus on ways to address an individual's functional needs, rather than providing a particular service.

Partnering with local business community, Japan: Where Canada tends to talk about providing services, Japan talks about providing communities that make it possible for older adults to stay in their homes and communities. In Japan, this has involved innovative partnerships with companies such as banks and grocery stores which are well positioned to act as early warning systems for elderly with functional challenges. For example, every 7-Eleven convenience store in Japan now functions as a "safe house" to assist seniors who appear disoriented. Employees attend training sessions conducted by local cities and towns on how to recognize and deal with people showing symptoms of dementia.

Long-term Care Insurance, Japan: In 2000, Japan also implemented a long-term care insurance system (LTCI) under the slogan ‘from care by family to care by society' in response to calls, particularly from women's groups, to help address the rising caregiving burden on families. The mandatory program, which is administered by municipalities, is a key component of Japan's community-based integrated care system. The LTCI requires all Japanese residents over 40 years old to pay into the program which provides institutional, home and community-based services to anyone over 65 who needs them. The beneficiary's level of need and quantity of services is determined by a standardized questionnaire on daily living activities and a report from the enrollee's physician that is reviewed by a local committee. Learn more

Programs for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly(PACE), U.S.: With a 20-year track record of proven success, PACE is considered the international gold standard for the delivery of integrated care for at-risk frail older persons. The Medicare and Medicaid program helps older adults stay independent, healthy, connected to friends and family and living at home. PACE programs have been shown to be an effective model that reduces unnecessary hospitalizations and rehospitalization.

How does it work? An older person (average age of 83) is picked up at their door and brought to a day program where they are fed, have their medications checked and asked how they are doing. An interdisciplinary health and support team is available to cover the entire spectrum of care. The team includes doctor, nurses, social workers, physical/occupational/speech therapists, home care attendants, day/health centre workers, transportation coordinators, dietitians, recreational staff, and bus drivers.

Who is the most important person on the interdisciplinary team? The bus driver, because they see the living conditions of the older person and how they are coping with functions like mobility on both good days and bad days.

How is the PACE model scaled up? Small communities leverage the assets within their own area and neighbouring towns and cities to build the scale necessary to sustain a PACE program:

- Rural PACE Model #1 - Northland PACE Senior Care Services, North Dakota: If a rural community is too small to support its own PACE centre, one can be established in the nearest larger town or city. In North Dakota, for example, the small rural community of Dickinson was able to service 130 people by sharing administrative costs with Bismarck, about 160 km away. Bismarck has a PACE day centre and clinic attached to a nursing home, plus coordinated in-home services and transportation.

- Rural PACE Model #2 – Senior CommUnity Care, Colorado: Two rural communities, Eckert and Montrose, wanted a PACE centre but their populations were too small and resources too few. They overcame these limitations by partnering with others in their communities, including volunteers, disability organizations, county offices, and health and human services agencies.

VON Seniors Managing Independent Living Easily (SMILE), South-East Ontario: Research found this supported self-management model to be "very simple" yet effective. SMILE is a home and community support program managed by the Victorian Order of Nurses (VON) with community partners. The regional program provides daily living support to frail seniors who are at risk of losing their independence.

How does it work? VON case managers identify high-needs seniors at risk of going into long term care. They ask both the older person and their caregiver what they need and how they can help with activities like shopping, cooking, cleaning, respite, transportation or visiting friends. Case managers identify the most important "functional need", design an individualized care plan that utilizes both formal and informal supports, and then monitors outcomes. Case managers have a monthly budget envelope available for each client.

Independent Living (Disability) Community: The disability community has a long history of working with clients of all ages with physical and cognitive impairments – many of whom would otherwise be institutionalized. Many of the successful approaches developed by this community can be adapted to frail seniors, who like many persons with disabilities, have complex chronic health and social needs.

Assisted Living Southwest Ontario (ALSO): The ALSO model was established in 1938 to provide a comprehensive range of independent living supports for people with physical disabilities and acquired brain injury. In 2011-12 it received additional funding from the Eric St. Clair Local Health Integration Authority to expand its services to frail seniors with functional impairments. Under the model, each client is asked what services they need. They are then linked to a comprehensive "basket" of non-medical and medical supports for daily living in supportive housing sites and in their own homes.

How is the ALSO model scaled up? ALSO doesn't try to do everything at once. Instead, it builds capacity over time starting with:

- Phase 1: Attendant services, supportive housing, respite (e.g., this includes different sites where individuals can have their own apartment and access attendants around the clock).

- # of people served: 12-15 per building

- Phase 2: ALSO could not afford the cost of the needed public support worker (PSW) shifts so it partnered with a local nursing home to share the cost. This enabled ALSO to extend mobile and outreach services into the community to create "neighbourhoods of care" for clients and caregivers living in their own homes. Services are provided 24/7 on a scheduled or will-call basis to cities like Windsor, Ontario, as well as neighbouring rural areas. It has resulted in some people who were in long-term care facilities or in hospitals being able to move back into their homes. It has also created a more stable schedule for ALSO's outreach staff.

- # of people served: an additional 30-35 clients

- Phase 3: ALSO is building new collaborations with Community Care Access Centres, the Alzheimer's Society, VON and a local hospice. Such collaborations have several advantages: they wrap services around high needs individuals and ease transitions; they improve quality and access; and they achieve system efficiencies through the use of specialized teams (e.g., dementia, palliative and acquired brain injury), shared assessments and shared services such as transportation.

- ALSO estimates that 500 high-needs individuals have been diverted from hospital alternative-level-of-care beds and long-term care placements since 2011

Discussion

Dos and don'ts for government:

- Incent change: F/P/T governments cannot provide all the solutions, but they can incent change through laws, regulations, funding and other supportive measures that shift the paradigm from reactionary health care to health promotion and prevention. Solutions should come from governments with the resources to invest and from communities which will ultimately be responsible for implementing these solutions.

- Take a stand on where we want to go: F/P/T governments need an enabling framework, or at a minimum a clear statement, on what type of society we want for our older citizens. This would help drive integration of home and community care and primary healthcare as local actions could be aligned around a common national goal. A framework should include equity and access as key goals, and indicators to track and measure. Denmark went much further 20 years ago with legislation that effectively ended construction of conventional nursing homes and shifted the focus to helping people live at home for as long as possible.

- Avoid the temptation to regulate: Governments should not apply healthcare-type regulations to community-based and informal health support services. Rather, look for opportunities to train and support these individuals.

Building neighbourhoods of care: Increasingly, innovative initiatives are being driven from the ground up to build supportive communities. This requires looking beyond the healthcare system and partnering with multiple local stakeholders (e.g., municipal services, local business, schools, faith organizations, service clubs). When thinking about future partnerships, think about where people live.

From healthcare to health: Shift the conversation from healthcare to health. Identify what keeps people healthy and independent. Local environments, including non-health care assets like housing, transportation and social connectedness play key roles.

Broaden the "unit of care": Include informal carers and social networks (e.g., family, friends, neighbours) and look at what can be done to support them.

Take a holistic approach: Don't think of an individual providing an individual service to an individual person. Instead, think about interdisciplinary networks of support and how we can support them to provide the widest possible range of health and social supports.

6. Care Innovations for Older Persons Across Rural Canada

Samir Sinha, Director of Geriatrics, Sinai Health System and Associate Professor, Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto

Programs or other interventions that work in urban areas do not always work in rural communities. Local solutions need to address the unique characteristics and needs of diverse communities. This includes the individual circumstances that can affect seniors' needs, such as health, language, gender, ability, finances, access to social supports, Indigenous identity, ethnicity, religion and sexual orientation.

Policymakers also need to recognize the changing demographics at play in rural areas. More baby boomers are entering their senior years just as more young adults are moving to larger centres for education and jobs. This out-migration contributes to the social isolation of those who remain, and to a shrinking workforce able to provide the service and health care supports many of the older generation need to remain in their homes and communities.

Untapping the hidden workforce

Rural communities with small and declining populations often struggle to have enough doctors and nurses, let alone specialists like geriatricians. Long-term care facilities are also constrained by economies of scale (i.e., they need to be able to fill a certain number of beds before locating in a community).

An alternative to this traditional healthcare approach is to widen the scope of practice for "mid-range" professionals like nurses, paramedics, pharmacists and other providers like community health workers. These providers have wider-scopes of practice that are not often utilized in urban settings. Paramedics are increasingly being recognized as a 24-7 community resource that can be utilized to provide enhanced primary, emergency and preventative care, particularly in rural areas.

Emerging community paramedicine models: Community paramedicine (CP) has emerged as an innovative 24-7 resource in rural Canada. Research has found that in rural communities where doctors and even home community care nurses are in short supply, the one consistent resource is the availability of paramedics.

CP programs have evolved as models of best practice in several Canadian provinces and in countries such as the US, UK, New Zealand and Australia. CP has resulted in decreased emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Three examples of emerging CP models across rural Canada include:

- Extended Primary Care (Long and Briar Island, Nova Scotia): A local physician sees patients on the island about once a week and paramedics visit seniors at home between appointments to provide regular check-ups.

- Preventative Home Visits for High-Risk Users (Renfrew County, Ontario): Renfrew County's long term care home partnered with local paramedics to ensure that vulnerable seniors on its waiting list received home visits at least once weekly. Paramedics perform basic health checks such as blood pressure testing and help clients with regular exercises and making sure they are eating well. The model was found to reduce by half the number of 911 calls and emergency room visits from these individuals, as well as fewer hospitalizations. The community paramedic program also costs significantly less ($10,000/client/year) compared to a long-term care home ($60,000/client/year). As well, the paramedic visits permanently removed some seniors from the long-term care home waitlist. The model is also increasingly being used by community nurses who need help serving a growing number of clients.

- Remote Health Monitoring and Chronic Disease Management Support (Several Ontario communities): Federal funding (via Canada Health Infoway) was made available so that paramedics, working with local primary care providers, can visit people with conditions like congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The model leverages local resources and technology to strengthen a rural community's primary care.

Geriatric outreach models of care: There is a shortage of geriatricians and geriatric psychiatrists in Canada, and those we do have are largely concentrated in urban areas. Two geriatric outreach models of care were presented:

- Flying in specialists: This model has proven "somewhat useful" in serving rural or remote areas. It is far less disruptive for clients than having to travel by bus or plane to a city where healthcare professionals may not speak their language or appreciate their local context (e.g., housing and community supports). However, this model does have drawbacks; it is not always the same doctor that visits each time so people have to continually retell their story. In addition, the professional flying in may not know the local context, such as housing situations, community supports, etc.

- Enhanced outreach model of care: This "village effort" model leverages the expertise of urban centres with the capacity and needs of local communities. In the James Bay region, for example, the Weeneebayko General Hospital has adopted a model of integrated geriatric care that includes paramedics, translators, local health workers, and geriatricians from urban centres who work with the local community-based teams and primary care providers. In these models, the community identifies high-risk individuals using high-risk screening principles and methods. The community then works with the geriatrician to create a comprehensive care plan that allows for ongoing continuity of care and follow-up between the patient, geriatrician and community-based team.

A systematic review led by Dr. Sinha (publication pending) found the key components of an enhanced outreach model of care should:

- Incorporate active community engagement by identifying what the community wants and needs.

- Integrate with local care systems, including local primary care providers and the community health work force. One model that proved effective for ensuring continuity of care was including the geriatrician's cellphone number and email on medical charts so that patients and their family members could call if they had a question.

- Build capacity and leadership of local care providers, e.g., training local providers in geriatric care principles and practices..

- Employ high-risk screening principles and methods and provide home and environmental assessment. In this model, local community health workers were responsible for identifying high risk individuals in their community, based on their functional limitations. This model makes it the community's responsibility to identify high-risk individuals.

- Involve direct specialists in longitudinal care and support.

- Deliver culturally safe and appropriate care. For example, if the fly-in team was new to the community, local residents would organize visits (e.g., local sweat lodge, former residential school) to build relationships and trust with patients and their families.

What to keep in mind when developing models of care and support

The needs of our highest users: It is important that the support and services provided consider the needs and challenges of the health system's highest users. These are often socially isolated seniors with multiple chronic problems and functional impairments. For example, technology can be leveraged to provide care (e.g., tele-rehab) and improve social connections (e.g., a weekly phone call). Likewise, enabling frail seniors to continue living at home often depends on having elder-friendly housing and transportation that leverage local community assets (e.g., SMILE and PACE models).

Setting realistic expectations: Not every rural community will have enough frail seniors or health workers to support a long-term care facility. As most rural seniors say they want to age in place, focus on leveraging the capacity that exists and developing resources and supports that make sense.

Discussion

Changing entrenched perceptions: A common belief, especially in rural communities, is that having a doctor, hospital and a long-term care facility are the main health supports you need as you grow older. Many physicians also believe these new models will mean less of a role for them and a loss of their patients. Rather than imposing "big city solutions" on rural areas, start with an open dialogue that empowers the community to identify their needs and wants. It can start with a simple question: "what does health care and health look like in your community?"

For example, a community may not have enough capacity to support a long-term care facility but it could still have access to millions of dollars in government funding for elder care. What is the best way to spend that money to ensure the greatest local impact? This approach shifts the conversation from what the community may lose, to what it stands to gain, such as better transportation, better housing and more PSWs.

One participant cautioned that some rural communities will still need a long-term care facility even if they lack economies of scale. In these cases, a case for opening a nursing home could be made on the basis that rural elderly generally use healthcare services less than urban elderly—savings that could potentially be transferred to a local long-term care facility. In addition it should be recognized (and accepted) in decision making that it is often the case that rural cost of services will be greater than the same urban service.

Training local residents to be PSWs: Some rural and remote municipalities are taking the initiative to develop assisted living centres. The challenge is finding enough PSWs to staff these communal homes or services. Rather than recruiting PSWs from other countries, two Indigenous communities partnered with the Red Cross to provide PSW training to people who had lived in the community their whole lives. Not only were jobs created for local residents, it also ensured that seniors were supported by people who know them, their local context and their language (Cree).

Recognizing and rewarding volunteers: There are many successful informal care networks in Canada that use peer-to-peer training and minimal resources to provide simple supports to vulnerable seniors. Much of the work is done by volunteers who may receive a small honorarium for travel. More needs to be done to value, recognize, support and incentivize these volunteers.

Knowing how and when to use technology: Technology is defined in a very broad sense, everything from remote monitoring and telemedicine to canes and phones, or as one person suggested, having a neighbour look out their window each morning to see if their elderly neighbour has turned on the lights.

No one-size-fits-all: There is no single technology that can be applied to every rural community. It depends on the local assets of each area; for example, something as simple as a telephone reassurance program where local organizations regularly call seniors who live alone. Another example is tele-rehab classes that seniors can watch on their televisions or computers.

Supporting home support workers: A recent project in the Yukon tested a different model. Vulnerable elderly were provided with a computer tablet which was used when community support workers visited to connect with a geriatrician or other specialist (e.g., occupational therapist or physiotherapist). While the program was successful in improving client's learning and problem solving skills, the tablets themselves proved problematic (e.g., not always functional or plugged in). Seniors who had their own devices preferred to use them over one that was provided. One additional benefit was that home care workers who were in the home learned from the specialists as well.

Empowering nurses to "visit" multiple patients at home: eShift is a secure, smartphone app that enables a registered nurse in a city, with the help of a local PSW, to remotely and simultaneously care for up to six patients who live at home. It was developed by the South West Community Care Access Centre in London, Ontario to enable one nurse to provide overnight care to several palliative patients at home. eShift was selected as an Accreditation Canada National Leading Practice, acknowledging it as a "sustainable, creative and innovative service" of national significance.

Using technology to connect youth and seniors: One AGE-WELL project used WeVideo software so that grade 6 and 7 students at Nak'albun Elementary School in north central British Columbia could record Elders telling their stories. The project helped to strengthen linkages between Elders and youth to preserve cultural wisdom.

Perhaps the biggest technology issue – transportation: Several speakers and participants identified the lack of access to transportation as one of the biggest challenges facing frail seniors who want to continue living at home. It makes it difficult to attend medical appointments and contributes to social isolation. The Ontario government recently released a new action plan called Aging with Confidence which includes a commitment to connecting seniors currently underserved by public transportation with the services and supports they need. However, public transportation is only effective if it's used. This was a challenge in the Regional Municipality of York, Ontario where the majority of seniors preferred to drive or rely on a family member rather than take public transit. The municipality addressed the issue by creating the myRide Travel Training Program for customers of all ages and abilities who need additional knowledge and skills in order to use public transit independently.

Barriers to technology:

Internet access: There are still several rural and remote communities in Canada that have limited or no access to the Internet which can limit the expansion of web-based technologies. This will become less of an issue over the coming months and years as online connectivity improves in rural areas. At the same time, seniors are the fastest growing group of Internet users.

Socioeconomic status and education: AGE-WELL researcher Dr. Janet Fast found that the main barrier to using technology is not age, but an individual's socioeconomic status, education, as well as the perception that they don't need a computer. These limitations affect caregivers as well as frail elderly. Another AGE-WELL researcher, Dr. Claudine Auger, is developing MovIT-PLUS, an Internet-based app that provides family members and other informal caregivers with remote monitoring, support and training on the use of assistive technologies (e.g. mobility and communication aids).

7. Challenges and Opportunities to Integrating Community Care for Older Adults in Rural Communities

Grace Warner, Associate Professor, School of Occupational Therapy, School of Nursing, Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, Dalhousie University

Having a great innovation is only the first step. Successfully implementing an innovation is often the bigger challenge. In research circles this is referred to as "implementation science": the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings into routine practice (Eccles & Mittman, 2006). In practice, implementation science frameworks should be used to guide how to improve implementation of research findings (Nielson, 2015).

At the local level, what works in one rural community, for example, may not necessarily work in another. For instance, addressing the challenge of integrated community care for older adults starts with recognizing the particular needs of older adults in diverse rural areas; the local context matters.

Integrated care for older adults

When determining who is on the community care team, think more broadly than traditional healthcare providers. A community care team can also include social service professionals, community volunteers and family members. The key issue is how well these individuals work together as a team to provide coordinated community care:

Case management functions: Integration of care is improved by having a coordinator or point person that the senior or family member can contact. If that individual changes, the transition needs to be smooth and the family needs to know. Different point people can have different roles at different times as long as the family is notified of any changes.

Integration of care between local physicians, specialists and community services: When a local health authority tried to implement a stroke clinic in a rural Nova Scotia community they encountered resistance from local physicians. The main issues included: poor communication between the health authority and family physicians; family physicians trusting that their patients would get appropriate care; and coordination of care between specialists and family physicians. Family physicians were reluctant to refer patients to specialists they didn't know. To overcome this challenge, a workshop was developed. A local family doctor led the workshop that involved fellow physicians, specialists and representatives from the rural health district. Having a local "champion" resulted in improved communication between rural physicians and specialists.

Family as part of the care unit and team: It is important for medical professionals to consider the needs of the family when evaluating the needs of the older client. A recent research project with community-based occupational therapists and physiotherapists highlighted the rural realities of long distances and wait list pressures that created barriers to visiting older clients in their homes more than once. As a result, it often fell on family caregivers to implement a therapist's care plan and motivate the client. Although most professionals did not consider addressing the health needs of family members as within their scope of practice, they did feel it was important to educate family caregivers on how to care for the client and reassure them that they are part of the care team.

Complex care needs – What works, what doesn't work

Assessing frailty early: Early assessment and intervention are key to supporting frail seniors and minimizing the incidence of adverse events. The Nova Scotia Health Authority developed a frailty strategy (PDF) and within that piloted the Frailty Portal – the first web-based tool of its kind in Canada and one that has garnered interest from other jurisdictions across Canada. The Frailty Portal helps primary care providers (i.e., doctors and nurses) identify, screen and improve access to, and coordination of streamlined services for persons experiencing frailty, which increases the ability of primary care providers to care for frail elderly patients.

When evaluating the portal the research team identified enablers and barriers likely to influence the intervention's continued use and scalability, such as:

- How well the innovation fits within a primary care provider's practice routine. For example, busy care providers are less likely to implement an innovation that takes valuable time from their busy schedules. One enabler is for the provider to delegate work to other team members, but this can be a challenge for solo family practices.

- If there is a local, provincial or national strategy or funding mechanisms that provide incentives for implementing the intervention.

- If the primary care provider believes frailty is important to assess, such as those that have a large number of geriatric patients.

Lessons learned from palliative care: There is much that can be learned from the palliative approach to care. For example:

Training hospice volunteers: The Navigating Connecting Accessing Resources Engaging (NCARE) program is a patient-centred approach that trains hospice volunteers to assist those with serious illness and their families to facilitate the transition from curative to palliative care. Volunteers partner with a nurse navigator to advocate, facilitate community connections, coordinate access to services and resources, and promote active engagement of older adults with their community. NCARE was successfully piloted in 2015/16 with funding from the Canadian Frailty Network. Several knowledge products (e.g., implementation manual, training manual, evaluation tools) are being developed to extend the program to communities across Canada.

An evaluation of the piloted NCARE program identified several benefits and challenges:

| Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Increased confidence in being able to ask for help | Volunteers unsure about their role expectations, contributions to care, and how to measure performance |

| Having someone knowledgeable and available | Healthcare providers need to recognize the role, knowledge and expertise of volunteers |

| Knowing there was backup when needed | Different knowledge and view of palliative care can result in lower referrals from health care professions to volunteers |

| Helping put things into context | Volunteers need to understand the larger palliative care system |

| Bringing awareness of available resources | Patient confidentially is a particular challenge for volunteers in rural areas where everyone knows everyone |

Recommendations

- Using implementation science frameworks (e.g., Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research) when evaluating innovative interventions helps uncover critical factors that affect implementation at multiple levels.

- Taking a quality improvement perspective, this type of evaluation allows factors to be addressed so interventions can be successfully implemented.

Discussion

Evolving policy frameworks: The federal government's use of bilateral agreements to provide federal home and community care funding to P/Ts will allow investments to consider jurisdictional differences. This more flexible approach helps to ensure targeted funding goes where it is intended. The Common Statement of Principles on Shared Health Priorities and the bilateral agreements also include a commitment to report on results to Canadians through common indicators to measure pan-Canadian progress on the agreed priorities.

A health workforce plan: The F/P/T Committee on Health Workforce focuses on workforce issues, including health workforce planning. Several provinces are also working on health workforce planning. For example, Ontario is identifying what works or not, and why, and how successful innovations can be scaled up and evaluated. One participant suggested that F/P/T governments need national, P/T and regional strategies on human resources for health that encompass older rural seniors (i.e., an overarching plan and plans within the plan). The plan should include targeted actions and measureable outcomes. In 2017, the WHO released its Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030.

Valuing the role of PSWs: There needs to be greater recognition and support for PSWs.

Adopting a principle of equity: One participant suggested adopting a principle of equity to help guide decisions related to diverse elderly populations in rural areas. A principle of equity would prompt the necessary questions to be asked as to who has access to health and health care, who doesn't, and whose voices are not being heard.

Adopting a broad concept of "home": Broadly defining "home" to include other community-based living arrangements (e.g., single family home, assisted living or other supportive housing) would assist F/P/T jurisdictions in developing housing policies that assist rural elderly persons. Other countries such as Denmark have taken this approach.

Broadening our definition of "caregiver": Research on aging in place in New Brunswick found that many seniors are stoic and reluctant to ask their children for help with daily tasks like snow shovelling, cooking, dog walking or yard work. However, they will seek help from other people they trust, including neighbours and friends.

Leveraging the strengths of rural areas: Rural areas have fewer services and resources than urban areas but they often have a stronger sense of community and strong local networks that can be leveraged to assist older residents.

Consultation and capacity are critical: Ask local residents what they want but ensure you have the readiness and capacity to respond. Rural residents are more likely to help implement innovations for which they see a clear need.

Overcoming language barriers: In New Brunswick—Canada's only official bilingual province—health-related services are not always available in English and French in minority communities and rural areas which makes accessing these services more difficult for seniors and their family caregivers. One solution is to connect to a translator or bilingual facilitator via videoconferencing. This approach could also be used for older immigrants who speak neither English nor French.

Family physicians need to be part of the primary care team: Integrated healthcare does not have to be physician-led, but a physician does need to be part of the team. Research shows it results in better mortality and morbidity outcomes. However, rural family physicians often have no funding to participate in teams. Nurses and any other additional staff are usually paid out of the doctor's salary. There is also the ongoing challenge of too few family physicians within rural areas of Canada.

More resources are needed to scale up successful local innovations: A 2015 report by the federal Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation recommended the creation of a 10-year Healthcare Innovation Fund with funding of $1 billion annuallyFootnote 9. It also recommended that funding and staff for the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement and the Canadian Patient Safety Institute be folded into a new Healthcare Innovation Agency of Canada, which would include a focus on scaling up and spreading innovations.

Sharing what works: Communities are not always aware of innovations that have been successfully implemented in other parts of Canada. The federal government could publish a national catalogue of examples of successful innovations for rural elderly that includes a description of the intervention and where to go more information. In Canada, Accreditation Canada's affiliate organization, Health Standards Organization, hosts the Leading Practice Database, a free online resource that highlights innovative healthcare and service practices that organizations can use to improve effectiveness and efficiency.

Community-driven research: CIHR could look into funding rural community-driven research, supported by a network of researchers, to evaluate promising local innovations. This type of approach is currently taken with several projects involving Indigenous communities. However, as rural communities have limited resources, it would be unrealistic to expect them to contribute funding to such projects. It was noted that about one-third of the budget of CIHR Institute of Aging can be used for new initiatives (excluding open competitions) and that the institute is currently refreshing its strategic plan. This could provide opportunities for funding more community-driven research.

Learning from Indigenous communities: Caring for elderly people is not a new concept for rural and remote Indigenous communities. Other parts of Canada can look to northern Indigenous communities for ideas and inspiration and examples of successful innovations.

8. Guided Discussion: Building an Inventory of Examples

Following the above four presentations, a guided discussion took place. BBE participants were prompted to discuss: "What promising activities and practices are you aware of that integrate and/or connect home and community care with primary health care for Canada's rural elderly population?" The table below provides a summary of the promising activities and practices shared by participants.

| Promising activities and practices | Key characteristics | Additional information |

|---|---|---|

| Engaging rural communities | ||

| Raising the Profile Project, British Columbia | The Raising the Profile Project (RPP) is a provincial network started in 2016. Its goal is to highlight the key role played by non-profit and municipal community-based seniors' services in supporting seniors to build new social connections, remain physically and mentally active, and retain their independence for as long as possible. The network consists of municipal and non-profit organizations around BC, seniors who are volunteer leaders, as well as provincial organizations that support the work of the community-based seniors' services sector (CBSS). Province-wide community consultations were completed in the Spring of 2017 to bring together regional communities to identify ways to support and sustain the CBSS sector in BC. | |

| Knowledge hub, British Columbia (working title) | Scheduled for launch in January 2018. This distributed learning model aims to build capacity and cohesion within the community-based seniors services (CBSS) sector, as well as to support improved connections with larger institutional partners (e.g., municipalities, health authorities, Ministry of Health) with the goal of supporting older adults with increasingly complex needs to live in their own homes and communities for as long as possible. The Knowledge Hub will be supported through the United Way's Active Aging Department, with initial funding from the Ministry of Health and the United Way. Content areas include:

|

|

Spaces for sharing best practices, British Columbia |

British Columbia is creating spaces for dialogue and action at a community level within each of its regions with the intention of rolling out into local health areas, at a more community-based level, and then holding annual regional forums where the provincial strategy is localized to each community. Seniors, local primary and community care providers, community-based services sector and other stakeholders (e.g., public transportation) meet to discuss the needs of various communities and develop a central intake and triage process. This is a partnership between community-based organizations, several funding partners, including all levels of government, and is initiated and managed by United Way. |

|

| Community Health Boards (CHB), Nova Scotia | CHBs were established in every community with the aim of empowering communities. They are comprised of community members, including active seniors, who focus on improving the health status of individuals and communities. They contribute to health-system accountability by facilitating an exchange of information and feedback between the community and the Nova Scotia Health Authority (Health Authorities Act, Section 62). | |

| Integrated care | ||

| Enhanced geriatric outreach models of care, Ontario | This "village effort" model leverages the expertise of urban centres with the capacity and needs of local communities. Key components include: active community engagement; integration with local care systems; building capacity and leadership of local care providers; high-risk screen and assessments; involvement of direct specialists; and culturally safe and appropriate care. In the James Bay region, for example, the Weeneebayko General Hospital has adopted a model of integrated geriatric care that includes paramedics, translators, local health workers, and geriatricians from urban centres who work with the local community-based teams and primary care providers. In these communities, they identify older individuals at high-risk and then work with the geriatrician to create a comprehensive care plan that allows for ongoing continuity of care and follow-up between the patient, geriatrician and community-based team. The Weeneebayko Area Health Authority also partnered with the Red Cross, local educational authorities and a college to develop culturally appropriate PSW training program aimed at local residents. |

|

| Broaden the vision for the community care team, non-location specific | When determining who is on the community care team, think more broadly than traditional healthcare providers. A community care team can also include social service professionals, community volunteers and family members. Have a coordinator or point person that the senior or family member can contact. Good communications across the team is essential. One model that proved effective for ensuring continuity of care was including the geriatrician's cellphone number and email on medical charts so that patients and their family members could call if they had a question. | |

| Primary Health Care Networks, Saskatchewan | This "accountable community-based care" model provides coordinated health services that are client-centred, community designed and team delivered. Each network is tailored to the needs of each community and includes a range of coordinated services and linkages with agencies and organizations to address other factors that influence health. | |

| Ross Clinic Home Visit program, Newfoundland and Labrador | Newfoundland and Labrador has a successful family physician and nurse practitioner (with pharmacist support) home visit program for high-needs frail elderly patients (many of whom are cognitively impaired). Individuals are identified by their doctors or during a hospital visit. It has resulted in a 50% drop in emergency visits, reduced re-hospitalization and reduced healthcare costs. This program is in St. John's but could be scalable for most urban and rural communities. | |

| Telegerontology Program, Newfoundland and Labrador | This pilot study was undertaken to optimize a remote monitoring method for managing the care of people with moderate to late stage dementialiving at home in rural Newfoundland. The intervention consisted of a home geriatric assessment by a family physician and nurse practitioner as well as a video recording of the home for a remote occupational therapy assessment, including advice for caregivers (e.g., falls reduction). Regular follow-up with the patient and caregiver was provided via Skype. Compared with the control group, there was a major reduction in long-term care admissions, significantly fewer falls and dramatically reduced health care costs. It is currently being explored for broad implementation by the province's largest health authority, Eastern Health. | Global ACE Forum 2017 [ PDF (318 KB) - external link ] Canadian Research Information System |

| Frailty Portal, Nova Scotia | This first web-based tool of its kind in Canada helps primary care providers identify frail seniors early and develop appropriate care plans. | |

| Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), US | An older person is brought to a day program where an interdisciplinary health and support team is available to cover the entire spectrum of care. On days when older persons do not come to the day centers, they may receive support services at home. This Medicare and Medicaid program helps older adults meet their health care needs in the community instead of going to a nursing home or other care facility. Most of the 170 PACE programs have shown to be effective. | Aging Gracefully: The PACE Approach to Caring for Frail Elders in the Community |

| Social prescribing and Community Navigator, UK | Instead of prescribing pills to elderly people, more family doctors and other healthcare professionals in the UK are prescribing a range of local non-clinical services (e.g., walking, a cooking club, art class or other community or social services) that can improve an individual's physical and mental health. The model has been shown to free up physician's time, prevent costly hospital stays and lead to a range of positive health and well-being outcomes. Social prescribing was named by NHS England as one of 10 high impact actions. However, robust and systematic evidence on the effectiveness of social prescribing is limited. Example of social prescribing: In Hertfordshire, UK the Herts Valley Clinical Commissioning Group (the National Health Service organization responsible for planning, designing and buying health services on behalf of an area of 627,000 people) offers "social prescribing" through its "Community Navigator Scheme". Aimed at people who may have a range of different support needs, GPs (as well as other health and social care professionals) write the patient a "social prescription" to a Community Navigator (i.e., refer the patient to a Community Navigator). Community Navigators work with the patient to connect ("prescribe") them with a range of needed local, non-clinical services, often provided by the voluntary and community sectors, ensuring that the patient remains well and independent. |

|

| Financing | ||

| Long-Term Care Insurance, Japan | All Japanese residents 40 years and older pay into long-term care insurance premiums. The program is administered by municipalities and is a key component of Japan's community-based integrated care system. It allows elders and their families to choose the community-based services and service providers that best meet their needs, such as adult day care, home help, respite care and visiting nurses. | Long-Term Care Insurance System of Japan [ PDF (1.6 MB) - external link ] |

| Independent living | ||