Ethics Guidance for Developing Partnerships with Patients and Researchers

- Acknowledgements

- Purpose of the Guidance

- Consideration of Indigenous perspectives

- Part I – Patient Engagement in Research – Reflections on Trust

- Part II – Guidance for Specific Roles in the Research Lifecycle

- Stage 1: Priority setting and planning

- Stage 2: Development of the research proposal

- Stage 3: Internal and external scientific review of the research proposal

- Stage 4: Ethics review of the research proposal

- Stage 5: Oversight of a research project

- Stage 6: Recruitment of research participants

- Stage 7: Data collection

- Stage 8: Data analysis and interpretation

- Stage 9: Translation and exchange of research knowledge.

- Stage 10: Evaluation and quality assurance

- Real Life Examples of Patient Engagement

- Glossary

- Frequently Asked Questions

- References

- Additional Resources

Acknowledgements

In 2015, the CIHR Ethics Office initiated a project to develop ethics guidance for research partnerships involving patients. Patients include people with personal experience of living with an illness or other health condition, as well as informal caregivers such as family and friends. This initiative responded to a gap identified by the Patient Engagement Working Group of Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) SUPPORT Units, as well as by other stakeholders at conferences and workshops.

In 2016, after the CIHR Standing Committee on Ethics endorsed the project, CIHR formed a Working Group to lead development of the guidance. The Working Group was co-chaired by the Manager of the CIHR Ethics Office and a public member of the CIHR Standing Committee on Ethics. It was made up of equal numbers of patients and experts from relevant fields of research. These members brought diverse experience and expertise, including Indigenous perspectives.

Members of the Working Group were:

- Nicolas Fernandez (Co-chair), Patient partner, CIHR Standing Committee of Ethics public member, and Assistant Professor, Center for Applied Pedagogy, Faculty of Medicine, University of Montreal

- Genevieve Dubois-Flynn (Co-chair), Manager, Ethics Office, CIHR

- Alexandra King, Member of the Nipissing First Nation (Ontario), and the Cameco Chair in Indigenous Health, University of Saskatchewan

- Michael McDonald, Professor Emeritus of Applied Ethics, University of British Columbia

- Jean Miller, Patient partner, and Patient Researcher with the PaCER (Patient Community Engagement Research) Program, O’Brien Institute for Public Health, University of Calgary

- Ron Rosenes, Patient partner, community health advocate, and Chair of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, Chair of the Community Advisory Boards for HPV-SAVE, CHANGE HIV and PROOV-IT research teams

- Donald Willison, Program Director and Associate Professor, Health Services Research, Institute of Health Policy Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto

- Cathy Woods, Patient partner, and co-lead of the Patient Council and Indigenous Peoples’ Engagement and Research Council of the Can-SOLVE CKD initiative

The Working Group developed a first draft of the ethics guidance through a collaborative consensus-based process. After targeted consultations refined the draft, broad public consultations were held from November 2018 to February 2019. CIHR and the Working Group wishes to thank all the groups and individuals who provided input during this consultation process. This feedback has improved and enriched the guidance.

Purpose of the Guidance

This guidance was designed to help researchers and patients develop research partnerships in the design or conduct of research – a process known as patient-engaged research. This kind of research is similar to community-engaged participatory research. However, patient-engaged research also brings the living or lived experiences of patients to the research activity (see Box 1).

The guidance and accumulated wisdom in the document draw on the experiences of the authors, comments during consultations, and the academic and non-academic literature in this area. It intends to contribute to a conversation about the topic rather than to provide a final word on the issues. As well, this guidance seeks to move beyond simple “dos and don’ts” by suggesting ways to improve patient-engaged research.

This work builds on the SPOR Patient Engagement Framework and the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, 2nd Edition (TCPS 2). SPOR-funded research teams and other initiatives, organizations, and institutions are encouraged to adapt the guidance for use by anyone involved in partnerships between patients and researchers.

While the guidance was written primarily for patients and researchers who come together for research, they may well help a broad range of stakeholders. These could include institutions that foster or house patient-engaged research; research funders (including CIHR); those who play a role in reviewing and overseeing this type of research (including research ethics boards); and those who study this type of research. As such, the guidance has been written in a style that is meant to be broadly accessible. Footnotes and references have been kept to a minimum. However, the document includes a list of resources and references for further reading.

Consideration of Indigenous Perspectives

The Working Group, with its deliberate consideration of Indigenous Peoples in Canada and their issues relevant to research, came together in reconciliation. With the support of CIHR, the Working Group intends this guidance to be one small step in contributing to implementation of reconciliation. It is also hoped that the various Indigenous-specific contributions found herein will resonate with other peoples. Further, in adopting and implementing guidance, it is hoped that patients, researchers, institutions, and funders will consider their respective roles and responsibilities with regard to our collective efforts to promote healing and reconciliation.

Part I – Patient Engagement in Research – Reflections on Trust

The first section of Part 1 reflects on how to build trust with patients engaged in research. It presents overarching ethical considerations, building on the core principles of respect, concern for welfare, and justice. The second section identifies six major ethical concerns that can arise during the research cycle. It then lists questions for both researchers and patients related to these concerns.

1. Overarching ethical considerations

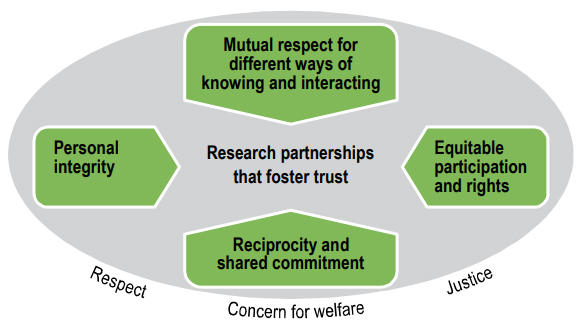

There are four core considerations to build research partnerships that foster trust:

- mutual respect for different Ways of Knowing and interacting

- equitable participation and rights

- reciprocity and a shared commitment to producing relevant research results

- personal integrity

Figure 1. Core considerations for ethical research partnerships

Figure 1 – Long description

Four core ethical considerations are important to building research partnerships that foster trust. These four considerations are:

- mutual respect for different Ways of Knowing and interacting

- equitable participation and rights

- reciprocity and a shared commitment to producing relevant research results

- personal integrity

These ethical considerations are grounded in the core principles of TCPS 2 – respect, concern for welfare and justice. These core principles apply to all types of research involving humans, including patient-engaged research.

The core principles of TCPS 2 – respect, concern for welfare, and justice – apply to all types of research involving humans, including patient-engaged research. This guidance focuses on ethical considerations that are relevant to patients as partners in health research, as opposed to patients acting as research participants. We recognize that patient-engaged research has much in common with community-based participatory research and has much to learn from principles used to guide research involving Indigenous Peoples.

1.1 Mutual respect for different Ways of Knowing and interacting

There are many enriching paths to knowledge. These include knowledge gathered through research disciplines, knowledge gained through living or lived experience, and Indigenous Ways of Knowing. Patient engagement allows researchers to access these various paths to knowledge by bringing diverse perspectives to health research. It can also help reveal “blind spots” – conscious or unconscious biases – that may interfere with scientifically-rigorous health research and the delivery of effective health care. Due to their living or lived experiences, patients often have valuable insights to bring to research. Neglecting these potential contributions can cause researchers to miss important aspects of the health issues they are investigating. This, in turn, can make it harder to implement their research.

Some of the qualities that support successful partnerships in research include:

- respecting other perspectives

- listening carefully

- communicating in plain language (using non-technical terms that the average person can understand)

- being non-judgmental

- using personal experiences constructively for deeper understanding

- being able to work collaboratively

- being interested in expanding one’s own knowledge and skills

These qualities help foster an environment of reflection and humility. This, in turn, allows exploration of various perspectives, strengths, and needs of researchers, patient partners, and research participants. Such an environment enables all members of the research team (including patient partners) to reflect on the direction of the research as it goes along.

1.2 Equitable participation and rights

Individual patients and their communities have every right to shape the research that is intended to benefit them, and to do so in meaningful ways throughout the process. Patient involvement in health research, for example, helps make the research activity more credible in several ways. First, it includes the diverse individual perspectives of patients who experience the health conditions being studied. Second, it includes community representatives who speak directly on behalf of others who live with those conditions.

1.3 Reciprocity and shared commitment to producing relevant research results

Reciprocity – exchanges based on mutual benefit and respect – is expressed in patient-engaged research in two ways.First, there is a shared commitment to developing research processes. Second, the processes produce results that are relevant to the health of patients. For this commitment to be honoured, patients must be treated as essential partners in this form of health research. They must be appropriately supported, recognized, and compensatedFootnote 2 for their contributions to the research process.

1.4 Personal integrity

Personal integrity involves openness, honesty, and promise-keeping. It also includes the accurate analysis and reporting of research. Finally, it includes recognition and appropriate management of factors that may hinder research, such as conflict of interest and bias.

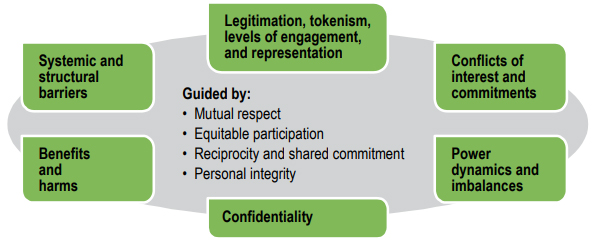

2. Ethical concerns across the research lifecycle

In this section, we identify major concerns that need to be addressed to maintain the trust relationships that are essential for successful patient engagement in research. These concerns are presented visually in Figure 2, and then discussed in the subsections that follow.

Questions and tensions may arise at various points in the research lifecycleFootnote 3 when patients are engaged as partners. Ethical concerns include:

- legitimation, tokenism, levels of engagement, and representation

- conflicts of interest and commitments

- power dynamics and imbalances

- systemic and structural barriers to patient engagement

- benefits and harms

- confidentiality of information

Figure 2. Reflecting on ethical concerns throughout the research process

Figure 2 – Long description

Ethical concerns may arise at various points throughout the research process. These ethical concerns include:

- legitimation, tokenism, levels of engagement and representation

- conflicts of interest and commitments

- power dynamics and imbalances

- systemic and structural barriers to patient engagement

- benefits and harms

- confidentiality of information

Reflections on these concerns should be guided by the four overarching considerations described in the previous section: mutual respect for different Ways of Knowing and interacting; equitable participation and rights; reciprocity and shared commitment; and personal integrity.

Key points and questions for reflection are provided under each of these concerns. Somewhat different questions are posed for patients than for researchers, institutions, and funders. However, everyone is encouraged to find answers in light of the four overarching considerations described in the previous section: mutual respect for different Ways of Knowing and interacting; equitable participation and rights; reciprocity and shared commitment; and personal integrity. The underlying aim is to build the trust that is essential to ethical and productive patient engagement in research.

2.1 Legitimation, tokenism, levels of engagementFootnote 4, representation

This sub-section looks at legitimation, tokenism, levels of engagement, and representation. It presents general issues that can arise for both patients and researchers that could interfere with the research process, project, or team. It then lists specific questions for these two groups.

Legitimation. “Legitimate” engagement of patients in research requires a partnership relationship. Patient groups whose capacity has been strengthened may even kickstart a research project, and then draw in researchers for their technical expertise.

Tokenism. “Tokenism” occurs when researchers include a patient voice in their project, but mostly ignore it. Research must take the perspective of patients seriously and draw on them to shape the research.

Levels of engagement. Patients may take on specific tasks in the research process based on their skill levels. For example, on a research team, they can lead focus groups and do interviews. At the most engaged level on a research team, they can also be partners in design and implementation, or co-authors of the various outputs from the study.

Representation. The engagement of a respected and trusted member of a patient community in a research project adds credibility both to the project and the researchers in it. These patients may come to represent the project in the community. As a result, they legitimize it in the eyes of others and, by their presence, encourage other patients to take part. Therefore, patients have an obligation to ensure their role respects their trust relationships with both researchers and their communities.

2.1.1 For patients

If you are bringing your personal living or lived experience of health issues to a research project, here are some relevant questions to ask yourself:

- Do I have both the knowledge and the commitment to make a meaningful contribution to the research project? If appropriate, can I get any needed additional help or resourcesFootnote 5 from the research team or my community to make such a contribution?

- Am I lending my credibility as an individual and patient to projects that I think might make a positive contribution to health care for other patients?

- Is the scope of my role clear so that I can decide if I am being meaningfully engaged or not?

- Is my presence in the project meaningful or am I only being used as a token, for example, to secure research funding or to just gain access to other patients? If my presence feels tokenistic, is there a way for me to voice my concerns?

- How am I processing my living or lived experience of my health condition to guide the research process and enhance understanding?

As a patient, you should ask yourself what it means to act as a representative:

- Am I speaking as an individual with living or lived experience, or am I expected to represent a larger community of people impacted by a health condition?

- If I am speaking as an individual with a living or lived experience, what parts of that experience am I willing to share? What parts should I keep private because these involve confidential relationships with other patients and caregivers? What parts do I simply want to keep private for my own reasons?

- If I am a member of a community with its own governing structures, has this community appointed me to represent them, or have I been elected by a membership to speak on their behalf? When am I speaking for just myself and when am I speaking for the community? In general, how do I fulfill my trust relationship with my community?

- Have I consulted enough with my community (for example, with other patients, patient groups, community leaders)? Do I represent the community, and does my community see me as acting on its behalf? Do I feel equipped to bring back valuable input to the project right through the research lifecycle?

You have three options if you feel that a proposed role in the project would be tokenistic, or that a research project would not benefit others. They are listed with increasing levels of seriousness and impact. You can:

- decline to participate

- propose ways to make your role more meaningful

- bring your concerns to people in authority or influence such as the lead researcher’s institution, community leaders, or a patient advocacy organization

2.1.2 For researchers, research institutions, and funders

Ask yourselves the following questions:

- Does the involvement of patients have a reasonable chance of increasing the usefulness of research to the relevant patient community? In what areas of the research can patients most meaningfully contribute?

- Are we willing to make the commitment and effort needed to fulfil a trusting relationship?

- How can we provide support such as training and administrative services to ensure patients can make greater contributions to research?

- Are we offering patients a meaningful role or is it only tokenistic?

- If we are asking patients to represent the views of others or their communities, are we giving them enough opportunities and resources to consult with others?

2.2 Conflicts of interest and commitments

This sub-section defines a conflict of interest and commitments. It presents general issues that can arise for both patients and researchers that could interfere with the research process, project, or team. It then lists specific questions for these two groups.

Definition. Conflicts of interest and commitment arise when two or more duties, responsibilities, or interests (personal or professional) are incompatible with the research activity. In other words, one cannot be fulfilled without compromising the other(s). Conflict can relate to an individual or institution.

Types. Conflicts can be potential, actual, or perceived. They may break the trust that underlies the patient engagement relationship. They may also distort a person’s judgment without that person being consciously aware of it.

Examples. Conflicts may arise because patients and researchers wear many hats:

- Patients may be members of another non-patient community, or have pre-existing or potential relationships or affiliations that could influence or interfere with how they carry out their role(s) in the research. These relationships or affiliations may be personal, political, commercial, or legal (for instance, duties of care such as legal guardianship).

- Researchers may have other roles (such as a health service provider). These may be seen as a barrier to engaging certain patients in the research. For example, clinician-researchers may not want to sit on the same committee as their own patients. However, this could mean that the patient, rather than the clinician-researcher, is kept off the committee. Some patients may find this unfair. For example, patients with a rare health condition or who live in a remote community may have few other opportunities to be engaged in research that is important to them. Therefore, situations and relationships like these need to be assessed carefully. In some cases, clinicians and their patients will sit on the same committee, and try to separate the research from the patient’s own health care. In this way, they can establish a productive working relationship as research partners.

Cultural differences. While conflicts will arise, the value of diversity and pre-existing relationships should be recognized. A conflict in one culture may not be seen as a conflict by another culture. Different cultures may also have different ways to address a conflict.

Management. Current or potential interests and commitments that could have an impact on the research need to be disclosed to appropriate individuals and institutions. However, conflicts of interest and roles must also be managed and minimized in a fair and appropriate way. For example, someone may not be able to make a full disclosure of interests and commitments related to the research because of confidentiality or harm considerations. In this case, the person should discuss these reasons with the person in charge of managing conflicts of interest to reach a solution. There may be times when disclosing interests or commitments is not enough to maintain the trust relationship. If this happens, additional actions are needed, such as vacating a conflicting role or leaving the research relationship. Conflicts of interest and commitment need to be assessed on a case by case basis. Following conflict of interest guidelines and checking with reliable third parties helps avoid or manage these problems.

2.2.1 For patients

Consider the following:

- Do I have personal, business, or other relationships that could conflict with my role in the research, and prevent me from acting in its best interests? Have I disclosed these relationships to others involved in the research and, where appropriate, to others in my patient group or community? How can I rearrange my involvement in the research to avoid such conflicts?

- Does the research team, institution, funding organization, or my community have policies and processes to help me identify and manage actual and potential conflicts?

2.2.2 For researchers, institutions, and funders

Consider the following:

- Do we have fair and transparent policies and processes to manage and minimize conflicts of interest and commitments? Do these policies recognize that patients are multi-dimensional and wear many “hats” (as research team members, community advisors, priority setters, etc.) and bring other interests, skills, and affiliations to their role(s)?

- If we are considering friends, neighbours, and family members as “patient representatives”, will they be independent? Will their personal relationships present a conflict of interest that cannot be managed effectively or inhibit their participation in research?

- Have we consulted with our patient partners on how their commitments and interests are likely to be viewed by other patient partners in the research?

2.3 Power dynamics and imbalances

This sub-section looks at power dynamics that can affect the engagement of patients in research. It presents general issues that can arise for both patients and researchers that could interfere with the research process, project, or team. It then lists specific questions for these two groups.

Power imbalances can affect the engagement of patients in research. Factors include:

- Status – This refers to differences in community or social status, expertise, compensation, and affiliations (for example, among members of a committee or research team).

- Control – This refers to different responsibilities for the funding of the research, and other accountabilities (by law and policy) at the level of the funder, institution, or research project. It also refers to possible community expectations for influence on its members. In particular, institutions and funders have a key role in addressing systemic and structural barriers to patient engagement.

- Information – This refers to differences in expertise, experience, and access (for example, to academic journals) to help with understanding the research.

- Health condition – Patients may have to attend to their health needs on a continuing or intermittent basis. If these needs are not accommodated, patients may find it difficult or impossible to contribute effectively to the research without risking their own health. As a result, they may decide to withdraw as research partners.

- Economic situation – Barriers may arise due to economic hardship, and prevent patients from acting as full-fledged partners in research.

- Divergent cultural protocols – Researchers and patients may come from different cultural backgrounds and have different expectations in regard to appropriate ways of interacting.

Each of these factors potentially affects the trust relationship that grounds successful patient engagement in research. Misuses and manipulation of status, control, and information may diminish and even freeze out meaningful patient engagement in research. Trust-building measures include:

- respecting the status of patients as partners in research

- having open discussion and consultation about power issues

- providing relevant information in a timely manner

Patients and researchers bring many types of expertise and a range of skills and competencies to the research project. Mutual respect and valuing of alternate knowledge systems and ways of knowing can resolve tensions around power imbalances. For example:

- Researchers have devoted their professional lives to researching a subject. They may have been drawn to a particular area of research or clinical practice based on personal, family, or professional experiences. They may have their own preconceptions of the experiences of the patients with whom they work. These preconceptions may be based on personal experience or on generalizations drawn from interactions with patients, which may or may not map onto the experience of other patients. Bringing these preconceptions to light with the help of patient partners can help address potential impacts of misconceptions and power imbalances.

- Patients with their living or lived experiences of a health condition can bring a range of relevant skills and experience. Patients, researchers, institutions, and funders should consider what skills and experience will be needed for particular roles. They must also consider what resources are needed to strengthen capacity (education, training, and support systems). Mentorship opportunities can also be part of capacity strengthening. For example, patient partners may provide training and development opportunities for other patients. The resource list includes examples of training tools and guides.

Information flows. Meaningful engagement of patient partners on research teams requires that information flows easily among team members. Patients must feel included in progress reporting and decision making. This may require efforts to develop a common language of communication between researchers and patients to bridge the gap between researcher-speak and patient-speak. The research team should agree on norms to ensure that information circulates correctly. This, in turn, will ensure that patients have access to the information they need to fulfill their role (for example, emails and library services). Meeting agendas should be set collectively and followed through in the meetings.

Cultural differences. Researchers and patients may come from different cultural backgrounds. As a result, they may have different, often unspoken, expectations about appropriate forms of social interaction. For example, many Indigenous communities expect food to be provided at meetings. In many academic communities, food is an optional extra at meetings. Also, different communities have different styles of conversation. At meetings where some people are outspoken, for example, patients may have a difficult time being heard.

2.3.1 For patients

Consider the following:

- Will I have access to the information, status, and power that I need to play a meaningful part in the research?

- Am I clear on the expectations that come with this role – my own, my community’s, and those of others?

- Will I need resources to help me fulfill this role? Are these resources available to me? What influence or control do I have over these resources?

- Will I receive the training I need to fulfill my role on the research team?

- Could I have a role in training patients and researchers to help expose or improve power imbalances, and deal with them?

- Do I understand the roles of other members of the research team and how I fit in?

- Do I feel that I am being treated equitably and with respect? Is my voice being heard, and my contributions acknowledged and valued?

2.3.2 For researchers, institutions, and funders

Consider the following:

- Have we included resources and support at the project planning stage? Will they allow patients to contribute meaningfully to research? Will they allow researchers and others to understand what meaningful collaboration is and what their responsibilities are?

- Have we established processes, support, and compensation? Will they allow patients to feel they are being treated equitably and with respect? Will they acknowledge and value the contributions of patients?

- Have we informed patients of the various roles on the research team? Have we told them about law or policy to which researchers, institutions, or funders may be held accountable?

- Is the project engaging more than one patient?

Depending on the roles of patients, it is good practice to engage more than one patient. Multiple patient voices provide a sense of both the diversity and commonality of living or lived experience. They also help balance requirements of the research project with other aspects of life. In this way, patients are not over-burdened and can give each other mutual support. Peer-to-peer mentorship between those patients with more task-related skills and experience and those with less can also be effective. Being the only person on a research team or committee without formal health or research-associated training can be intimidating.

- Have we reflected on our cultural expectations as researchers and institutional representatives? Have we recognized the generally unspoken assumptions we bring to our interactions with patients? Have we considered that patients may have different expectations around how they interact with researchers?

2.4 Systemic and structural barriers to patient engagement

This sub-section looks at systemic and structural barriers to engaging patients. It presents general issues that can arise for both patients and researchers that could interfere with the research process, project, or team. It then lists specific questions for these two groups.

Certain aspects of research may present potential systemic and structural barriers to patient involvement on the research team.

Systemic barriers are those policies, practices, or procedures that result in some people receiving unequal access or being excluded. On research teams, a systemic barrier may be tied to the long lag-times between phases of the research, e.g. from proposal development through funding, ethics review, data collection and analysis, and knowledge translation and exchange. Some barriers may be addressed through managing the expectations of patient partners. There may be practical issues around cash flows and the ability to compensate patients for the time invested in the project. In some cases, it may be necessary to compensate patients financially for their participation in the research. In other cases, receiving money may disqualify patients from social benefits. It is also important to budget for food, food restrictions, travel, and other expenses.

Structural barriers occur when one category of people is considered unequal compared to others. This relationship is perpetuated and reinforced by unequal relations in roles, functions, decisions, rights, and opportunities. Poverty, race, ethnicity, or lack of formal education are examples of potential structural barriers. There may also be access barriers to meetings, such as curbs or lack of elevators for individuals with mobility issues. Planned breaks may also be needed to accommodate the health needs of the patient partner.

2.4.1 For patients

Consider the following:

- How much time can I commit to the project? Can I commit to the project until it ends? Although the latter may not be an expectation, it should be discussed up front.

- Can my research partners accommodate any health conditions I have? For example, do they have a medical emergency plan in place at meetings? Do they schedule breaks between meetings to allow time to rest?

- Can my research partners help address the financial costs of participation such as compensating for lost wages or daycare expenses?

2.4.2 For researchers, institutions, and funders

Consider the following:

- Do all individuals understand processes and procedures about the research project? For example:

- There will be considerable lag between proposal development and funding. This includes delays associated with the need to revise and re-submit a grant for the next grant cycle.

- There may also be considerable lag between funding and research ethics review before being able to start the project.

- Have we addressed systemic and/or structural barriers that may inhibit or prevent the participation of patient partners due to their health condition, or their economic or social status? This includes:

- physical access barriers

- meeting times and duration – for example, the need for a break in a lengthy meeting

- appropriate and sufficient support provided around teleconferences, videoconferences, and in-person meetings

- Have we provided enough training for individuals with lower literacy levels whose living or lived experience is of value to the project?

- Are funds available to support patient partners for the time they have invested in the project during these periods when there are no project funds? For example, a funding agency might cover costs associated with proposal development. Funds might also come through the Vice President, Research at a university.

- If a patient partner cannot accept financial compensation for participation (e.g. if this would disqualify them for social assistance), what else could be offered? Non-financial compensation could include food at meetings, or the costs of transportation and accommodation for presenting to a conference.

2.5 Benefits and harms

This sub-section looks at benefits and harms from research. It presents general issues that can arise for both patients and researchers that could interfere with the research process, project, or team. It then lists specific questions for these two groups.

Through sharing their living or lived experiences of a health condition, patient partners can help to increase research benefits and reduce harms:

- For themselves. Patient partners can identify their own health needs so these needs can be accommodated in their roles in the research activity.

- For research participants. Through their living or lived experience of a health condition, patient partners are well positioned to advise other research team members. This advice could be about both potential harms and benefits for research participants.

- For the general patient population. Patient partners could identify potential harms to people affected by communication and use of the research results from, for example, stigmatization and discrimination.

- For knowledge translation and exchange. Patient partners could help inform health care providers and other patients of research results.

Patients and researchers should also be prepared to exit a partnership sooner than expected. For example, patient partners may feel too uncomfortable to continue. Their circumstances may also change, making it difficult to fulfill expectations. In addition, researchers may not be able to obtain funding for a project.

2.5.1 For patients

Consider the following:

- How might the research affect me personally? For example:

- Do I have any health conditions that could affect my ability to participate?

- Does my living or lived experience affect my feelings towards the topic?

- What am I expected to do? Are these expectations reasonable?

- Does the project have mechanisms to support me? For example:

- If the research activity triggers stressful memories associated with my living or lived experience of a health condition or circumstances, can an Elder help take care of the team for Indigenous research?

- What are the potential impacts of the research on other patients or my community?

- Could engaging in the research strengthen me?

For example:- Will I add to my own skills and experience?

- Can I make a positive contribution for the benefit of other patients, my community, and society?

- Does the research have potential benefits or harms that my colleagues may be unaware of?

- How can I best bring my living or lived experience of a health condition and what I learned in the research project to the awareness of community members and their health care providers?

2.5.2 For researchers, institutions, and funders

Consider the following:

- Are we giving patient partners opportunities to provide information about potential benefits and harms of the research for research participants?

- Do we have mechanisms to hear from patient partners about potential benefits and harms associated with their roles in the research process, and to support them when needed? Have we built the necessary resources, e.g. human, financial, and time, into the budget?

- When the research activity ends, how will we recognize and celebrate the contributions of patient partners, e.g. as co-authors? Can we help interested patients to find other opportunities for meaningful engagement?

2.6 Confidentiality of information

This sub-section looks at confidentiality issues. It presents general issues that can arise for both patients and researchers that could interfere with the research process, project, or team. It then lists specific questions for these two groups.

Some information gathered throughout the research lifecycle should be kept confidential. This includes, for example, applications submitted for scientific or ethics review, or information that would reveal the identities of research participants. Researchers, institutions, and funders should ensure that all involved can uphold all expectations of confidentiality, and that appropriate policies and procedures are in place. Patients may also be a source of expertise with respect to the expectations of particular communities around confidentiality and privacy. In some Indigenous communities, for example, only specific members of a family may be permitted to tell their family stories.

2.6.1 For patients

Consider the following:

- What are the expectations for confidentiality associated with the kinds of information I will be dealing with? What policies and procedures are there to guide me?

- Am I prepared to share responsibilities to uphold protections for information provided in confidence? Do I need more support or resources to fulfill my responsibilities?

2.6.2 For researchers, institutions, and funders

Consider the following:

- Are there appropriate policies, procedures, training, and supports in place for respecting expectations of confidentiality? Is there a mechanism to deal with breaches of confidentiality?

- Is everyone showing the same respect for confidentiality that is expected from patient partners?

Part II – Guidance for Specific Roles in the Research Lifecycle

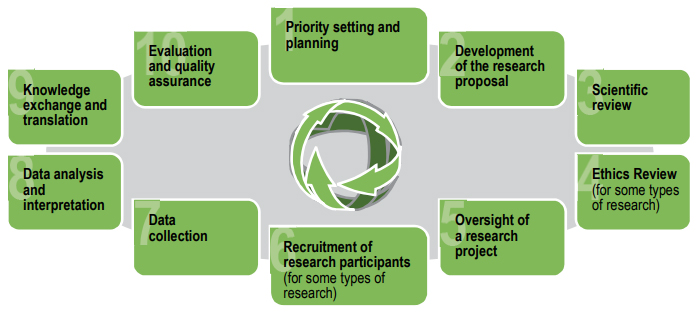

The ethical concerns and reflections described in Part I are relevant to all roles throughout the research lifecycle. Part II applies the ethics guidance to demonstrate good practices in 10 specific stages of the research lifecycle: priority setting and planning; development of the research proposal; scientific review; ethics review; oversight; recruitment of participants; data collection; data interpretation; knowledge transfer and translation; and evaluation.

Overview

We aim to promote broad engagement of patients across all stages of the research (see Figure 3). This ethics guidance is mainly focused on the engagement of patients in roles other than as participants. However, a patient can be a research participant, and also take on other relevant roles depending on the insights or skills they can offer. In a large-scale population health study, patients may be research participants and also have a formal voice on a committee to advise on the overall direction of the study. A patient can also be a research participant for a first phase of a study, and then take on an advisory role for a subsequent phase.

When institutions or funders engage patients to sit on independent scientific review committees or ethics review committees, those patients might also be partners on research teams. To avoid a conflict of interest, they would not review proposals from those teams.

Figure 3. Key stages in the research lifecycle

Figure 3 – Long description

The key stages in the research lifecycle are:

- Priority setting and planning

- Development of the research proposal

- Scientific review

- Ethics review (for some types of research)

- Oversight of a research project

- Recruitment of research participants (for some types of research)

- Data collection

- Data analysis and interpretation

- Knowledge exchange

- Evaluation and quality assurance

Stage 1: Priority setting and planning

Priority setting can take place in various contexts. For example, a funding agency could be developing its strategic plan or a research initiative on a specific emerging issue; a research centre dedicated to a particular health condition or population group could be determining how it should invest its funds; or a research team at the earliest stages of exploring knowledge gaps and stakeholders’ interests is seeking a new research direction.

| Priority setting and planning: Examples of patient roles | Guidance: |

|---|---|

|

For patients:

|

For researchers, institutions, and funders:

|

Stage 2: Development of the research proposal

| Development of the research proposal: Examples of patient roles | Guidance |

|---|---|

|

For patients:

|

For researchers:

|

Stage 3: Internal and external scientific review of the research proposal

| Scientific review: Examples of patient roles | Guidance |

|---|---|

|

For patients:

|

For researchers:

|

|

For research institutions, communities, and funders sponsoring scientific review committees:

|

Stage 4: Ethics review of the research proposal

Under TCPS 2, institutions must establish or appoint research ethics boards to review the ethical acceptability of all research involving humans. These research ethics boards are expected to have at least one community member with no affiliation to the institution. A community research ethics board may also review proposals involving Indigenous Peoples.

| Ethics review: Examples of patient roles | Guidance |

|---|---|

|

For patients:

|

For institutions and communities:

|

Stage 5: Oversight of a research project

A long-term project might have decision making or advisory boards as part of its internal governance structure. A data and safety monitoring board may be established for some studies to help monitor the safety of research participants.

| Oversight: Examples of patient roles | Guidance |

|---|---|

|

For patients:

|

For institutions and communities:

|

Stage 6: Recruitment of research participants

| Recruitment: Examples of patient roles | Guidance |

|---|---|

|

For patients:

|

For researchers:

|

Stage 7: Data collection

| Data collection: Examples of patient roles | Guidance |

|---|---|

|

For patients:

|

For researchers:

|

Stage 8: Data analysis and interpretation

| Data analysis and interpretation: Examples of patient roles | Guidance |

|---|---|

|

For patients:

|

For researchers:

|

|

For institutions:

|

Stage 9: Translation and exchange of research knowledge

| Knowledge translation and exchange: Examples of patient roles | Guidance |

|---|---|

|

For patients:

|

For researchers:

|

|

For institutions:

|

Stage 10: Evaluation and quality assuranceFootnote 6

| Evaluation and quality assurance: Examples of patient roles | Guidance |

|---|---|

|

For patients:

|

For researchers, institutions, and funders:

|

Real Life Examples of Patient Engagement

(Disclaimer: CIHR is not responsible for the content of external web links)

| Institution | Patient partner roles include | Internet links |

|---|---|---|

Can-SOLVE CKD (Chronic Kidney Disease) Network |

|

|

Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) Research Institute: Research Family Leaders Program |

|

|

James Lind Alliance: Priority Setting Partnerships |

|

|

Canadian HIV Cure Enterprise (CanCURE) |

|

|

Living with HIV (LHIV) Innovation Team Grant- Community Scholar Program |

|

|

Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Networks in Chronic Disease – Selection Panel Review Guide |

|

|

American Cancer Society |

|

|

Manitoulin Anishinaabek Research Review Committee |

|

https://www.noojmowin-teg.ca/programs-services/manitoulin-anishinabek-research-review-committee |

Walmsley program of research into HIV and Healthy Aging (CHANGE-HIV) |

|

|

Patient and Community Engagement Research (PaCER) Unit, O’Brien Institute for Public Health, University of Calgary |

|

Glossary

Capacity strengthening: This involves giving people the tools to strengthen their existing capacities. This term is preferred over related terms such as capacity building or empowerment because this term recognizes that people bring their existing abilities, skills, and exercise of power to their engagement in research.

Community: A group of people with a shared identity or interest that has the capacity to act or express itself as a collective. A community may be territorial, organizational, or a community of interest. See TCPS 2.

Community member: Someone who self-identifies, and is recognized by the community, as belonging to a specific community. See definition of Community.

Conflict of interest or commitment: The perceived, actual, or potential incompatibility of two or more duties, responsibilities, or interests (personal or professional) of an individual or institution as they relate to the research activity, such that one cannot be fulfilled without compromising the other(s). This is adapted from TCPS 2.

Cultural safety: Respectful relationships can be established when the research environment is socially, spiritually, emotionally, and physically safe. Cultural safety is a participant-centred approach that encourages self-reflexivity among health researchers and practitioners. It requires an examination of how systemic and personal biases, authority, privilege, and territorial history can influence these relationships. Cultural safety requires building trust with Indigenous Peoples and communities in the conduct of research. Realizing cultural safety in health and well-being research entails understanding the social, political, and historical contexts that have resulted in power imbalances. It requires an individual to have cultural humility, competence, sensitivity, and awareness in determining relevant health research policies, programs, models, and projects with Indigenous Peoples. Meaningful and culturally safe practices refer to equity in health research and delivery. In a meaningful and culturally safe research environment, each person's identity, beliefs, needs, and reality are acknowledged. Participants feel safe based on mutual respect, meanings, learning experiences, and shared knowledge. Cultural safety ensures that the participating community, group, or individual is a partner in decision making. See CIHR Institute of Indigenous Peoples’ Health web site.

Ethical dimensions of research partnerships: In this document, we explore how patients and researchers can interact with each other in a respectful and socially beneficial way.

Experiential knowledge: Knowledge that is gained from living or lived experience. See definition of Living or lived experience.

Knowledge translation and exchange: A dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange, and ethically-sound application of knowledge. This process takes place within a complex system of interactions between researchers and knowledge users. It may vary in intensity, complexity, and level of engagement depending on the nature of the research and the findings, as well as the needs of the particular knowledge user. An example of knowledge translation is the communication of scientific findings in plain language for lay audiences, as well as many other ways in which new knowledge can be communicated and applied. See CIHR’s mandate in knowledge translation.

Living or lived experience of patients: Personal experience (in the past or on an ongoing basis) of living with a health condition, or caring for someone with a health condition. The concept of the expert patient comes from the recognition that living or lived experience can be the basis of expertise in knowing how a health condition and treatment affect the patient’s own body and circumstances. It recognizes that patients should have “the confidence, skills, information, and knowledge to play a central role in the management of life” Footnote 7 with their medical condition. Expertise from living or lived experience can also help inform research related to a patient’s health condition, as well as the ways in which the condition and treatment intersect with the social determinants of health (such as culture, social status, access to health services, etc.).

Participatory research: “A systematic inquiry that includes the active involvement of those who are the subject of the research. Participatory research is usually action-oriented, where those involved in the research process collaborate to define the research project, collect, and analyze the data, produce a final product and act on the results. It is based on respect, relevance, reciprocity, and mutual responsibility.” (TCPS 2, Chapter 9, Research Involving First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada, Article 9.12, Application).

Patients: An overarching term inclusive of individuals with personal experience of living with an illness or other health condition, and informal caregivers, including family and friends (based on the SPOR definition). This guidance was developed in support of SPOR and therefore uses SPOR’s broad definition of patients to encompass the range of people who may be engaged as partners in research. Other related terms are knowledge users, citizens, community members, etc.

Patient engagement in research: Patient engagement occurs when patients meaningfully and actively collaborate in the governance, priority setting, and/or design and conduct of research. This includes engagement in the analysis and interpretations of findings, and summarizing, distributing, sharing, and applying its resulting knowledge. This is based on the SPOR definition.

Patient-engaged research: Research in which patients contribute as patient partners.

Patient partners: Patients who are engaged in any of the roles in the research lifecycle.

Reciprocity: Reciprocity involves relationships that are based on mutual benefit and exchange, including, for example, the obligation to give something back in return for gifts received. This is adapted from TCPS 2, Chapter 9, Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples of Canada.

Research: An undertaking intended to extend knowledge through a disciplined inquiry and/or systematic investigation. See TCPS 2, Glossary.

Research participant: An individual who is involved in a research study and whose data, or responses to interventions, stimuli, or questions by a researcher, are relevant to answering a research question. See TCPS 2, Glossary.

SPOR: Canada's Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) is about ensuring that the right patient receives the right intervention at the right time. Patient-oriented research refers to a continuum of research that engages patients as partners, focuses on patient-identified priorities, and improves patient outcomes. This research, conducted by multidisciplinary teams in partnership with relevant stakeholders, aims to apply the knowledge generated to improve health care systems and practices. SPOR is a coalition of federal, provincial, and territorial partners.

Systemic and structural barriers to patient engagement: Systemic barriers are those policies, practices, or procedures that result in some people receiving unequal access or being excluded. On research teams, a systemic barrier may be tied to the long lag-times between the phases of the research (from proposal development through funding, scientific and ethics review, data collection and analysis, and knowledge translation). Structural barriers are circumstances where one category of people is attributed an unequal status in relation to other categories of people because of unequal relations in roles, functions, decisions, rights, and opportunities. Poverty, race, ethnicity, or lack of formal education are examples of potential structural barriers.

TCPS 2 – Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct of Research Involving Humans, 2nd Edition. This is a joint policy of Canada’s three federal research agencies: CIHR, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). To be eligible to receive and administer funds from the Agencies, institutions must ensure that research conducted under their auspices adheres to this and other policies of the Agencies.

Tri-Agency Framework: Responsible Conduct of Research, 2016 (RCR Framework): The RCR Framework sets out the responsibilities and corresponding policies for researchers, institutions, and the Agencies, that together help support and promote a positive research environment. The RCR Framework contains the Tri-Agency Research Integrity Policy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is there other relevant guidance that patients and researchers should be aware of?

The Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS 2) and the Tri-Agency Framework: Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR Framework) are relevant to the ethical conduct of research, whether or not patient partners are involved. The core principles of TCPS 2 (respect, concern for welfare, and justice) are demonstrated in soundly conducted patient-engaged health research. Similarly, the principle of research integrity found in the RCR Framework is essential to patient-engaged research.

Researchers funded by the three federal research councils (including CIHR) must comply with TCPS 2 and the RCR Framework. Patient partners on research teams may be in roles where they interact with research participants and therefore have responsibilities under TCPS 2. In some cases, patient partners may also be research participants. Similarly, the RCR Framework is relevant to patient partners who are members of a research team. For example, researchers should ensure proper acknowledgement of contributions to the research, and management of conflicts of interest.

While we consider TCPS 2 and the RCR Framework, we do not intend to add to, or modify, those policies. This document is intended as an educational resource, and not as a policy with compliance requirements. In addition, we have compiled examples of additional tools and guides developed by other organizations, in the Resources list at the end of this document.

Does patient engagement in research raise specific ethical questions and issues?

Patient engagement can generate a variety of ethical issues across the research lifecycle that need to be addressed. This document highlights questions – and key points of reflection – for patients, researchers, institutions, and funders, to help them think about how to do patient engagement in an ethical and meaningful way, and to turn these reflections into good practices.

Do patient engagement plans require review by research ethics boards?

Research ethics boards review research proposals to ensure that research involving humans will be conducted in compliance with TCPS 2. Such compliance includes appropriately respecting and protecting research participants.

Ethics approval is not required for involving patients in the planning or design stages of research. At the point of ethics review, patient partners may appear in three distinct roles that are relevant for research ethics boards to consider:

- As part of the research team. Research ethics boards assess the roles of members of the research team, particularly their interactions with research participants. For example, when patient partners are involved in participant recruitment and data collection and analysis, the research ethics board will want assurances from the lead researcher that patient partners will conduct these activities according to the core ethical principles of TCPS 2: respect, concern for welfare, and justice.

- As research participants, if patient partners also have this role. Here, research ethics boards need to ensure that participants will be respected and protected, with the added complexity that these participants are also involved in the research effort as part of the research team.

- As members of a community being researched or funding research, or as spokespersons for those communities. TCPS 2 addresses community participatory research, particularly in research involving First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples (see Chapter 9 in TCPS 2). We also provide some reflections on working with Indigenous communities in the Consideration of Indigenous Perspectives section.

Research ethics boards should be aware that partnerships with patients in research have the potential to:

- make research more relevant to the people the research is trying to assist;

- help determine what is acceptable to research participants; and

- improve the experience of research participation.

Thoughtful engagement of patients in research should apply the core principles of TCPS 2: respect, concern for welfare, and justice.

References

American Cancer Society (n.d.), Stakeholder Participation on Grant Peer Review Committees.

Anderson, J. A., Swatzky-Girling, B., McDonald, M., Pullman, D., Saginur, R., Sampson, H. A., and Willison, D. J. (2011), “Research ethics, broadly writ”, Health Law Review 19(3), 12-24.

Bourassa, C. (2016), “Powerful communities, healthy communities: Fostering cultural safety”, presentation at Sharing the Land, Sharing a Future: Marking the 20th Anniversary of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) Conference, November 2-4, 2016, Winnipeg.

Bourassa, C., Oleson, E., Diver, S., and McElhaney, J. (in press). “Cultural safety”. In K. Graham, D. Newhouse and C. Garay (eds.), Sharing the Land, Sharing a Future, University of Manitoba Press.

British Columbia First Nations Health Authority (n.d.), Definition of cultural humility.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (n.d.), Definition of knowledge translation.

Ermine, W. (2010), “Ethical space in action”, Video, McMaster University.

Ermine, W. (2007), “The ethical space of engagement”, Indigenous Law Journal, 6(1).

Flicker, S., Roche, B., and Guta, A (2010), Peer Research in Action III: Ethical Issues [ PDF (552.45 KB) - external link ], Wellesley Institute, York University and University of Toronto.

Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada (n.d.), Guidelines on Public Engagement.

HIV Community-Based Research (n.d.), Fact Sheet #2 – Recruiting Hard to Reach Individuals and Communities in Community-Based Research [ PDF (596.34 KB) - external link ].

HIV Community-Based Research (2014), Fact Sheet #3 – Managing Multiple Roles and Boundaries [ PDF (593.08 KB) - external link ].

James Lind Alliance (n.d.), Priority Setting Partnerships.

Lavallee, B., Diffey, L., Dignan, T. and Tomascik, P. (2014), “Is cultural safety enough? Confronting racism to address inequities in Indigenous health”, presentation at Challenging Health Inequities: Indigenous Health Conference, January 2014, University of Toronto.

Panel on Responsible Conduct of Research (n.d.), Tri-Agency Framework: Responsible Conduct of Research, Section 2.1 Tri-Agency Research Integrity Policy.

Panel on Responsible Conduct of Research (n.d.), Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, 2nd Edition, (TCPS 2).

United Kingdom, Department of Health (2001), The Expert Patient: A New Approach to Chronic Disease Management for the 21st Century.

United Kingdom, National Health Service (n.d.), Handbook for Researchers: Patient and Public Involvement in Health and Social Care Research [ PDF (2.1 MB) - external link ].

University of Ottawa (n.d.), Definition of cultural competence.

Williams, R. (1999), “Cultural safety – What does it mean for our work practice?” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 23(2), 213-214.

Additional Resources

(Disclaimer: CIHR is not responsible for the content of external web links)

CIHR:

Canada’s Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR)

- SPOR home page

- SPOR Patient Engagement Framework

- SPOR considerations when paying patient partners in research (May 2019)

- CIHR Jargon Buster

- SPOR Networks

- SPOR SUPPORT Units (in every region, with contact information)

Institute of Indigenous Peoples’ Health

Tri-Agency (CIHR, SSHRC, NSERC):

Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, 2nd Edition (TCPS 2):

- TCPS 2 Policy statement

- CORE Education module

- TCPS 2, Chapter 9, Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada

Tri-Agency Framework: Responsible Conduct of Research, Section 2.1 Tri-Agency Research Integrity Policy

External:

Research 101: A Manifesto for Ethical Research in the Downtown Eastside, 2018

Alzheimer Society:

- Supporting Research Recruitment: A Guide to Get Started [ PDF (3.35 MB) - external link ]

- Person-centered language [ PDF (190.48 KB) - external link ]

- The Canadian Charter of Rights for People Living with Dementia

- Meaningful Engagement of People with Dementia: A Resource Guide [ PDF (929.89 KB) - external link ]

Arthritis Research Canada: Workbook to guide the development of a Patient Engagement in Research (PEIR) Plan [ PDF (1.06 MB) - external link ]. May 2018

Canadian Patient Safety Institute: Engaging Patients in Patient Safety – a Canadian Guide

Centre of Excellence on Partnership with the Patients and the Public, University of Montreal: Patient and Public Engagement Evaluation Toolkit

Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario (CHEO) Research Centre – Research Family Leader program

HIV Community-Based Research (CBR): Fact Sheet #2 – Recruiting hard to reach individuals and communities in CBR [ PDF (596.34 KB) - external link ]

HIV Community-Based Research (CBR): Fact Sheet #3 – Managing Multiple Roles and Boundaries [ PDF (593.08 KB) - external link ]

Indigenous Peoples:

- Framework for Research Engagement with First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Peoples [ PDF (4.47 MB) - external link ]

- First Nations Health Authority. Cultural humility webinars

First Nations:

- Assembly of First Nations

- British Columbia First Nations Health Authority, especially Research-Related Resources

- Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project, especially articles about how to do research

Inuit:

Métis:

International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) Spectrum of Public Participation

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) - INVOLVE

- Resource centre

- National Health Service (NHS): Handbook for researchers: Patient and public involvement in health and social care research [ PDF (620.81 KB) - external link ]

Nuffield Council on Bioethics:

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2015): Children and clinical research: Ethical issues

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2015): The collection, linking and use of biomedical research and health care: Ethical issues:

- Participatory Evaluation approach

The Patient – Patient-Centered Outcomes Research

- Date modified: