Implementing positive change for Indigenous Peoples

Hotıì ts’eeda Northwest Territories SPOR Support Unit takes steps to implement the United Nations Declaration of Rights for Indigenous Peoples in health and wellness in the territory

Related stories

Hotıì ts’eeda (pronounced “ho-tee-tsay-dah”) is the SPOR SUPPORT Unit in the Northwest Territories. Hosted by the Tłı̨chǫ Government, the SUPPORT Unit connects organizations and communities throughout the territory to achieve health research and training goals.

Through an innovative project called Ełet’ànı̀ts’eɂah (pronounced “e-klet-a-neet-see-yah”), which means drawing on collective strength in the First Nations Tłı̨chǫ language, the SUPPORT Unit team is engaging Indigenous communities in a conversation about how to implement the United Nations Declaration of Rights for Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) with a focus on promoting health and wellness.

First adopted by the United Nations in 2007, UNDRIP establishes a universal framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world. The declaration consists of 46 articles, which cover everything from the preservation of Indigenous Peoples’ culture to attention to the rights and special needs of Indigenous Elders, women, youth, children, and persons with disabilities. Canada signed on to UNDRIP in 2016 and passed legislation in 2021 to support its implementation in this country.

The SUPPORT Unit is carrying out the Ełet’ànı̀ts’eɂah project in collaboration with a governing council of representatives from four Indigenous governments in the NWT, the Department of Health and Social Services of the Government of the NWT, and the Indigenous and Global Health Research Group at the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Medicine.

“In addition to talking with Elders, cultural knowledge holders, and Indigenous government representatives, we are working with the Western Arctic Youth Collective to address their views regarding the implementation of UNDRIP in health and health research,” said Dr. Stephanie Irlbacher-Fox, Scientific Director of Hotıì ts’eeda.

“The knowledge shared so far was used to develop a first draft of guidelines. This included insight and observations shared by Indigenous participants, researchers, health policymakers, program designers, and evaluators could do better at upholding Indigenous Peoples’ rights in their work.”

UNDRIP as a tool for Indigenous rights

Launched in 2017, Hotıì ts’eeda currently supports northern Indigenous residents in various areas, including a support program for Indigenous medical students, the development of community researcher capacity among NWT individuals and communities, and the use of Indigenous cultural competency training workshops for researchers and policymakers.

The Ełet’ànı̀ts’eɂah project is important because it promotes change by using UNDRIP as a mechanism to repair holes that exist in the fishnet of laws, agreements, and programs that currently affect Indigenous Peoples’ rights and wellness.

Starting in 1876, for example, residential schools separated Indigenous children from their families and subjected them to religious and cultural assimilation of colonial settlers. Though these schools closed in 1997, and the Government of Canada issued an apology, Indigenous Peoples still suffer intergenerational trauma that has led to social suffering.

In addition, treaties that were first established between Indigenous Peoples and the Crown regarding land occupation were not honoured and led to Indigenous Peoples being predominantly relegated to small parts of their traditional territories across Canada.

Thanks to the establishment of Indigenous governments in Canada, such as the Tłı̨chǫ Government in 2003, things are moving in a positive direction, and UNDRIP is providing the impetus for positive change.

“Ełet’ànı̀ts’eɂah is a profoundly transformative but multi-generational project,” said Dr. Irlbacher-Fox. “We’re approaching UNDRIP implementation guideline development through knowledge sharing and partnership with NWT Indigenous Peoples as ways to educate and guide researchers/policymakers. We believe that everyone is coming to the table wanting to do the very best research that they can – which involves incorporating Indigenous knowledge and culture – and we’re counting on that.”

Knowledge sharing on the land

The SPOR Support Unit’s annual meetings take place on the land outside of Yellowknife. The meetings involve Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, Indigenous self-government leaders, Elders, youth, and Indigenous community members. These meetings are opportunities to share scientific findings and Indigenous knowledge and engage in a conversation about the strategic directions of the SUPPORT Unit. Participants learn how land-based medicine such as willow bark can have similar benefits as aspirin at pharmacies. Non-Indigenous researchers learn about Indigenous culture and traditions such as beading.

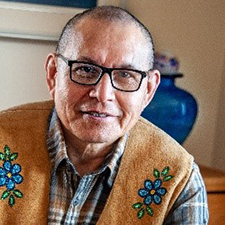

“When it comes to UNDRIP and Hotıì ts’eeda’s overall achievements, we have scientific findings translated by Elders in 6 or 7 different Indigenous languages at our annual meetings, so that the merits can then be explained to 10,000 residents in NWT’s Indigenous communities,” said Dr. John B. Zoe, who is the Tłı̨chǫ Chairperson of the governing council for Hotıì ts'eeda.

“Through self-governance in Tłı̨chǫ and other communities in NWT, we’re also taking an important step forward to identifying Indigenous needs with the help of organizations like CIHR. It’s part of a strengthening exercise for us. If we can share information with each other, Indigenous thoughts will be incorporated into the highest levels of positive change for health policy and outcomes, such as legislation.”

Indigenous youth to help sustain progress

To preserve these important political and health service advances, the Support Unit wants to ensure that Indigenous youth continue to receive education that’s respectful of their Indigenous knowledge and culture at universities.

“We’re always educating Indigenous youth so that they can identify with their land, their languages, their cultures, and their ways of life at a very early age,” said Dr. Zoe. “If they have that collective strength, they can continue to readjust negative systemic thinking that Indigenous People always need help by implementing more positive healthcare practices that are respectful of Indigenous ways of being. That way, Indigenous students can continue to maintain access to mentors, safe areas, storytelling, and Elders, and sustain the progress we’ve started to make to fix some of the holes in our fishnet.”

- Date modified: