The right care at the right time: Improving equity and access to quality primary health care in Canada

When you get sick, require a medical test, need a prescription, or want advice on how to improve your overall health, who do you normally turn to? For most Canadians, chances are they will turn to their family doctor or primary care provider.

But for more than 5 million Canadians – or about 15% of the population – this isn't an option because they don't have one. Dr. Emily Gard Marshall, a professor in the Department of Family Medicine at Dalhousie University, used to be one of those Canadians.

"When I first moved to Nova Scotia, I couldn't find a family doctor for three years – and I was working in the Department of Medicine!" Dr. Marshall recalls. "At the time, Nova Scotia had more doctors per capita than anywhere else in the country, so in theory, I shouldn't have had a hard time finding a doctor. But I was having a hard time, and I wasn't the only one."

Dr. Marshall's personal experiences eventually led her down a decades-long path of exploring and understanding the barriers Canadians face to accessing primary care, and finding ways of addressing those challenges so that "unattached patients" – that is, people who do not have a primary care provider – can be matched with a family practice.

"Relationships between patients and their family doctor or primary care provider often develop over many years, which is beneficial for patients because the provider gets to know their medical history and health goals," Dr. Marshall explains. "But beyond that, primary care is an important entry point into the health care system overall. If someone needs a specialist, for example, they likely need a referral from a family doctor or nurse practitioner. Or, if someone has complex care needs and requires a targeted treatment plan, they will need primary care support throughout that process. When a patient doesn't have a primary care provider though, it becomes really hard for them to navigate those situations."

Lack of access to primary care can also have ripple effects on other parts of the health care system, as patients with no other options can end up in the emergency department to deal with chronic illness flare-ups or worsening symptoms. Some of those hospital visits, or even hospital admissions, could likely be avoided if patients had access to a primary care provider to help diagnose, treat, and manage their conditions at an earlier stage. Ultimately, this would save valuable time and hospital resources, plus result in better care for the patient.

"Sometimes people ask me how research can help address such a big problem," says Dr. Marshall. "I understand that people usually want to talk about resources first, so I tell them that we need research to design better models of care, to identify needs, and to develop novel approaches for making our health care system more equitable. Research is what helps us understand what is working, what is not, and why – and it's only with that information in hand that we can try to get the most for everyone out of our health care resources."

An interdisciplinary approach for an interdisciplinary challenge

While Canadians value and take pride in our country's strong health system, Dr. Marshall stresses that there is certainly room for improvement – including improving primary health care. Unfortunately, there is no "one-size-fits-all" approach to making improvements.

"Implementing a solution that solves one challenge could inadvertently create new, unexpected challenges in another area of our health system," Dr. Marshall says. Say, for example, we want to reduce the number of unattached patients in Canada and make it easier for them to find a family doctor. Governments could implement a policy that requires doctors to increase the number of patients they accept, but this could quickly lead to physician burnout and reduce the quality of care they provide, which would bring us back to square-one.

"In this sense, finding feasible solutions can often feel like a balancing act," Dr. Marshall says. "These are complex problems that require equally complex solutions. That's why, in my research, I work with patients, physicians and health care providers, policy makers, community organizations, and researchers from diverse fields so that when we assess these issues, we're tackling them from all angles and trying to find the best possible solutions for everyone involved."

Tackling these issues involves collecting data from various sources to get as complete a picture as possible of the barriers Canadians face in accessing primary care. This includes conducting interviews with unattached patients and health care providers, administering and analyzing surveys, assessing health policies, and reviewing administrative health data records for trends over time. As Dr. Marshall and her team collect these data, it becomes easier for them to identify where gaps exist, why they exist, and how they may be able to address them.

"We know through our research, for example, that women are more likely to be attached to a doctor or primary care provider than men, in part due to reproductive health needs throughout their adolescent and adult life and socialization," she explains. "They may visit a doctor as a teenager to be prescribed birth control, then revisit in their early twenties for their first PAP test, then perhaps meet with their doctor several times during pregnancy, if they choose to become pregnant. Men, on the other hand, don't have as many touch points with their doctor. Plus, we know there is stigma that can prevent some men from seeking help for their physical and mental health, so this is also a barrier we need to consider and address in our research."

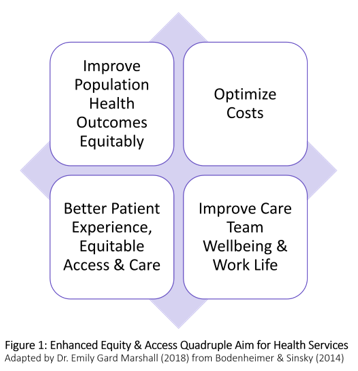

Optimizing health care through the Quadruple Aim

Long Description

Figure 1: Enhanced Equity & Access Quadruple Aim for Health Services

Adapted by Dr. Emily Gard Marshall (2018) from Bodenheimer & Sinsky (2014)

- Improve Population Health Outcomes Equitably

- Optimize Costs

- Better Patient Experience, Equitable Access & Care

- Improve Care Team Wellbeing & Work Life

Dr. Marshall and her team are ultimately working to support primary health care across what experts call the Quadruple Aim. Dr. Marshall has adapted this model that advocates for improving Canada's primary health system by addressing four areas: patient experience, care team experience, cost, and overall population health, to explicitly address enhancing equity and access.

Using the Enhanced Quadruple Aim as a model reinforces how intricately connected these four areas can be, as making changes to improve one has the potential to affect the others – both positively and negatively. For example, making changes to improve the patient and physician experience could lead to better overall population health, but it could also result in an increased cost to the health care system. Similarly, changes to reduce costs could result in poorer patient and physician experience, and by extension, minimal improvement in population health.

"The Quadruple Aim framework is a fantastic model to show how health care is about much more than just providing timely care," Dr. Marshall says. "Our health system is exactly that – a system. When one part of the system isn't working, it's going to affect the rest of the system as well. So, if we want to help more unattached patients access primary care and find a family doctor, we need to consider all of the other factors that are involved in that process as well."

The goal of the Quadruple Aim framework – and Dr. Marshall's research more broadly – is about ensuring patients can access the right care, at the right time, by the right provider, using the right type of care. If these efficiencies can be achieved, Dr. Marshall says this will also help reduce costs and save money because our health system will be optimized to its greatest potential.

"I think back to when I first moved to Nova Scotia and couldn't find a family doctor, and how frustrated I was that I couldn't get the care I needed," Dr. Marshall says. "We have such an amazing health care system here in Canada, but there are still some people who are falling through the cracks. I hope that my work will help support those patients and ultimately make it easier for all Canadians to get the care they need."

- Date modified: