Evaluation of CIHR's Commercialization Programs

Final Report 2015

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

160 Elgin Street, 9th Floor Address Locator 4809A Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0W9

Acknowledgements

This report was authored by Carmen Constantinescu, Senior Evaluation Analyst.

The evaluation was carried out by an Evaluation Working Group which, during the different phases of the evaluation, included: Carmen Constantinescu, Krista Davidge, Kim Ford, Joanne Tucker, Michael Goodyer, David Peckham, Martin Rubenstein, Kwadwo Bosompra, Fazila Seker, Karen Dewar, Janet Scholz, Michelle Peel, Bert van den Berg, Étienne Richer, and Nicolay Ferrari.

Cover photo courtesy of National Research Council of Canada (NRC)

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Evaluation Scope & Purpose

- Profile of CIHR's Commercialization Programs

- Knowledge Translation & Commercialization

- Collaborations & Partnerships

- Capacity development

- Program Design & Delivery

- Program Relevance

- References

- Appendices

Executive Summary

In 2005, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) developed its Commercialization and Innovation Strategy to provide a framework for transforming health research into action, improving the quality of life and stimulating economic development through discovery and innovation.

The Strategy was implemented through a number of programs and initiatives that addressed one or more of the strategic components, including: Industry-Partnered Collaborative Research Operating Grants (IPCR), Collaborative Health Research Projects (CHRP), Science to Business (S2B), Proof of Principle Phase I and Phase II (POP I and POP II).

Evaluation Purpose, Scope and Approach

The purpose of the evaluation was to assess the relevance and performance of the commercialization programs to identify best practices and lessons learned to inform future programming and meet the requirements of the Financial Administration Act and the Treasury Board of Canada's Policy on Evaluation (2009). The following aspects of CIHR's commercialization programs were examined: knowledge translation and commercialization; knowledge creation; collaboration and partnership; capacity building; design and delivery; and relevance.

The evaluation covers the time period from the creation of each of the programs until the end of fiscal year 2012-13. The evaluation methodology included literature and document review, key informant interviews and a survey of funded researchers. To better contextualize the performance of the commercialization programs, where feasible, comparisons were made with CIHR's Open Operating Grants Program (OOGP), Regenerative Medicine and Nanomedicine Initiative (RMNI) and Centres of Excellence for Commercialization and Research (CECR) Program.

Key Findings

Knowledge Translation and Commercialization

Knowledge translation (KT) and the application of research results into practice are necessary activities for the commercialization of health research.

- Findings indicate that researchers funded through the CIHR commercialization programs are generating key commercialization outcomes:

- presentations to industry and other partners (79% of funded researchers);

- provisional patents (74%);

- patent applications filled (64%);

- non-disclosure and confidentiality agreements (64%);

- invention disclosures (61%); and

- patents granted (41%).

- Researchers funded under POP I reported higher percentages for commercialization outcomes compared to the other programs. OOGP researchers successful in commercialization, CECR and RMNI researchers reported higher commercialization outcomes compared to the IPCR and CHRP programs.

- A minimum of 42 different spin-off companies have been created or benefited from POP I and POP II program funding since 2001. Two examples of spin-off companies are presented below.

Company Name Principle Investigator Area of Research Impacts

Professor Shana Kelley, University of Toronto

Rapid detection system of known cancer biomarkers in prostate tumor tissue as an indication of disease progression

Developing the Xagenic X1 platform, a revolutionary diagnostic system, that allows the user to perform molecular diagnostic lab-quality assays in the physician's office

Large market opportunity created by significant unmet medical need for point-of-care diagnostic solutions

Employs more than 40 people

Revenues from worldwide sales of molecular diagnostics are estimated to be $6.2B in 2014

Tissue Regeneration Therapeutics (TRT)

Dr. John Davies, University of Toronto

Progressive biotechnology with a focus on the commercial development of patented Human Umbilical Cord PeriVascular Cell (HUCPVC)

TRT has shown that the tissue around the vessels of the umbilical cord is the richest source of mesenchymal stem cells ever described

2014- TRT and Héma-Québec enter a definitive licensing agreement for the first human clinical trial of TXP-1

2013 - TRT raises $3.25 Million to accelerate the development of its Mesenchymal Cell therapeutics platform

- In terms of knowledge creation, the majority of funded researchers (79%) published at least one journal article per grant, with 45% of the IPCR researchers and 30% of the POPI researchers producing a joint publication with the private sector. Despite the challenges that researchers face in terms of the pressure to publish and limited support for translational research, the tensions between commercialization and open science are not irreconcilable and could be envisioned as complementary elements of a more holistic innovation framework (Caulfield, 2012). For example, the scientific productivity (i.e., journal articles published) of POP I researchers normalized by grant duration and grant amount is similar to OOGP researchers, although knowledge generation is not a main objective of POP I.

The evaluation identifies a number of best practices in developing a strong culture of innovation including: movement from "commercialization" to "innovation" as a guiding philosophy; encouraging entrepreneurship and industry-pull programs; and newer models of commercialization where resources are pooled to undertake research and commercialize multiple discoveries in a given field.

Collaborations and Partnerships

Collaborations and partnerships are central objectives for CIHR commercialization programs to ensure the stakeholders are involved early in the project so that "research uptake" increases.

- CIHR commercialization programs involved industry and other relevant stakeholders to a higher degree during all the stages of their projects compared to OOGP funded researchers.

- Although not a requirement for the POP I program, 65% of the POP I funded researchers involved partners during their funded projects.

- The majority of the funded researchers under IPCR (70%) and POP I (69%) stated that the funding through CIHR commercialization programs was an incentive to work with a partner. However, 60% of IPCR and 66% of POP I researchers would still have chosen to work with a partner if the dedicated funding through the CIHR commercialization programs would not have been available. The main reasons for working with a partner were partners' expertise and to ensure increased knowledge transfer and use; IPCR funded researchers stressed the importance of financial contributions.

- A set of challenges have been identified by the industry partners: the cultural differences between industry and academia, the lack of control of the companies over research funds (i.e., researchers might divert from the original plans), monitoring project performance, and the timing of CIHR competitions (it was suggested that frequency to be increased to better align with industry needs and timelines).

The best practices identified for enhancing partnerships were: promote grants that are specifically designed to strengthen engagement and partnership (e.g., Natural Science and Engineering Research Council's Interaction and Engage grants); involve multinational companies and have research and development (R&D) agreements with partners early on; offer programs in partnership with other relevant organizations; and increase the awareness of new discoveries by organizing workshops and seminars, so that researchers can find "takers" for their good ideas and create demand within user sector (e.g., industry).

Capacity Development

Training in the field of commercialization has been the main objective of the S2B program and has been encouraged through the other CIHR commercialization programs (CHRP, IPCR, POP I & II).

- The majority (76%) of S2B awardees declared that the S2B program exceeded or fully met their expectations by contributing to the development of their commercialization skills and knowledge. However, the program represents a very small investment compared to the other CIHR commercialization programs and CIHR funding budget overall.

- IPCR, POP I and POP II, involved a variety of HQP and research personnel in their projects, but a small number of them were actually trained in the area of commercialization.

- Thirty percent (30%) of the funded researchers surveyed reported a lack of commercialization skills as a challenge in moving their discovery/innovation toward commercialization. More widely, there is a perceived shortage of entrepreneurs in Canada and almost all participants voiced the need for Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs) to have stronger commercialization expertise.

In terms of the best practices for capacity development in the area of health research commercialization, facilitation activities are seen to be more important than offering training opportunities; other international granting agencies facilitate the recruitment of specialists that assist the TTOs and researchers throughout the commercialization process and experts within the organizations who are in touch with companies.

Design and Delivery

All five programs were received well by stakeholders and are delivering the intended outcomes at the program level:

- POP I – the most highly used and sought grant; this grant was considered a best practice in supporting early stage research in the commercialization pathway.

- POP II – seen as providing funding to validate early discoveries when the projects are at their highest risk and investors are not interested yet.

- IPCR – well perceived by the partners; it facilitated strong collaborations between the universities and industry including better understanding of each other's needs and priorities.

- CHRP – not very well known outside the research community (only 3 TTOs of the 10 had dealings with CHRP program); those who had experience appreciated it for the interdisciplinary collaboration.

- S2B – very well received by the funded awardees for contributing to the development of their entrepreneurial/commercialization skills and knowledge.

Nevertheless, the following improvements to design and delivery were identified:

- Program awareness – the programs require more promotion, in particular for IPCR and CHRP; and there is a need for a stronger TTO involvement as a facilitator for these programs.

- Review process – it was suggested that CIHR involve more industry experts in the peer review process to better evaluate the projects' commercial potential as well as give researchers the opportunity to present their proposals.

- Competition process – participants suggested increasing the number of competitions per year as well as shortening the time for peer review, decision, and communication of the decision.

- For POP I and POP II, offering grants with longer duration (or at least more flexibility with duration) would be an improvement, given the nature of the research funded through these programs.

- Accountability – there is a need to have clear timelines, milestones, and tracking/monitoring systems; there is a greater need for monitoring and evaluation of CIHR commercialization programs.

The following best practices were seen for other international funders: the approach to fund the entire spectrum from early research to SMEs (offer a wide range of programs); assistance programs that support the main programs and assess market readiness; having the right skill set in the peer review process; and implementing a stage-gate model based on performance milestones.

Program Relevance

A number of trends were identified for the Canadian health research commercialization landscape that indicate an ongoing need for health research commercialization funding: a lack of venture capital/angel investors; downsizing of internal R&D by industry, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry; a perceived lack of clear government strategy on innovation and commercialization; challenges related to intellectual property (IP) law and policies; pressure on TTOs to be very productive with fewer resources; and a lack of funding for early stage health research commercialization.

- The majority (92%) of the funded researchers surveyed believe that there is a need for the federal government to continue to foster the commercialization of health research in Canada and more than half of the survey respondents (62%) identified "lack of funding for health research commercialization" as their most common challenge.

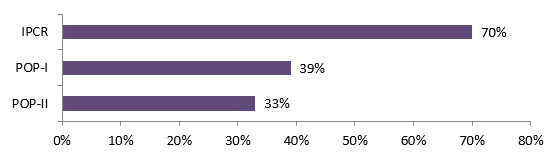

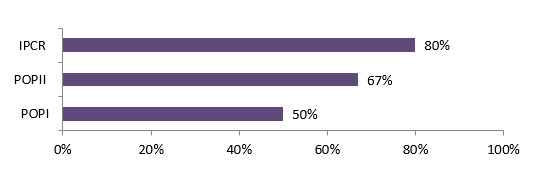

- At most half of the commercialization survey respondents (45% IPCR, 33% POPI and 50% POPII) received other additional financing for commercializing their health research during and/or within two years after their grant's finishing date.

Although it is recognized that funding is required for each stage of the commercialization pathway, funding early stage commercialization research is the most critical role that CIHR can play, especially given limited resources. The majority of funded researchers surveyed (94%) identified "early stage funding" as a priority area that CIHR should focus its commercialization programs on.

CIHR could play several other roles to enhance commercialization of health research in Canada:

- work with other stakeholders to develop a coherent, national strategy to promote innovation and health research commercialization;

- play a stronger role in enhancing human capacity (researchers, TTOs);

- support researchers in developing and facilitating partnerships with large and small industry;

- play a brokerage role in supporting sharing of new discoveries so they can be "taken up" in the commercialization pipeline; and

- track fundamental research for potential commercial outcomes.

Conclusions

This evaluation finds that CIHR commercialization programs have generated many positive contributions to the Canadian health research commercialization landscape. Each of the programs has its merits:

- CHRP program supported collaborations between researchers in health and engineering fields;

- IPCR facilitated partnerships;

- POP I program was seen as a best practice in supporting early stage research in the commercialization pathway;

- POP II supported projects to move further along the commercialization pathway; and

- S2B developed commercialization skills and job-readiness among awardees.

However, the scale of the impacts of these programs is small and needs to be understood in the context of programs' investments. To significantly shift the landscape of Canada's health research commercialization there is a need for a bigger vision, more support, and bolder actions as were identified in the best practices presented in this report.

Recommendations

Findings from the evaluation indicate that establishing a strong, innovative culture is a key preliminary step for Canada to achieve more success in the area of health research commercialization. For CIHR, an important first step to further foster an innovative culture within the agency as well as the health research community is to understand commercialization as part of a broader innovation continuum or ecosystem. Findings from the environment scan reveal that the term "innovation" and "valorization" are being used by most of the comparable international organizations consulted to capture the value created and the broader societal benefits that result from the translation, application, or extension of new or existing knowledge.

Recommendation 1: CIHR should adopt a definition of innovation that captures the broader social, economic and health benefits resulting from the use of health research to develop or improve goods, services, processes, organizations and systems.

Findings from the evaluation identify a number of trends that point to the continued need for CIHR funding to foster innovation and facilitate the commercialization of health research, including: a lack of venture capital, reductions in private sector R&D, and a need for funding to support early stage health research commercialization. In light of the available resources, the performance of existing programs, and other federal government investments in innovation, the most critical role that CIHR can play is to fund early stage commercialization of health research.

Recommendation 2: CIHR should continue to fund early stage commercialization research to support this critical phase in the commercialization process to test and validate the commercial potential of discoveries that addresses a key funding gap and unmet need among researchers and TTOs.

The evaluation findings underline the importance of collaborations and partnerships between researchers and potential research users to support the promotion of scientific discoveries to the commercialization pathway.

Recommendation 3: CIHR should play a brokering role in the area of innovation and commercialization in order to: facilitate interactions between researchers and the potential users of the research results to increase awareness, demand and uptake; and partnerships with other innovation and commercialization programs and intermediaries to coordinate and leverage investments across the innovation continuum. Specifically, CIHR should focus on:

- 3.1. Enhance partnering in existing programs and look to develop programs that are specifically designed to strengthen engagement and create partnerships between researchers and potential users;

- 3.2. Increase awareness of CIHR-funded discoveries by organizing workshops, seminars, symposia to facilitate an organized exchange of ideas, so that researchers can find "takers" for their good ideas. To facilitate this, it may be necessary to involve experts with industry and innovation experience to conduct outreach, establish connections and liaise with companies to promote and enhance industry "pull" of CIHR funded research results; and

- 3.3. Prioritize and focus investments to capitalize on existing investments and infrastructure in health research commercialization (e.g., CECR and BL-NCE programs) to maximize the use of future investments for health research commercialization.

Findings from the evaluation identify a number of areas of improvement to the design and delivery of existing as well as future programs to better enhance performance.

Recommendation 4: Specifically, CIHR should incorporate the following into the future design and delivery of commercialization and innovation programs:

- 4.1. Involve more industry experts in the peer review process to better evaluate the projects' commercial potential and to give researchers the opportunity to present their proposals;

- 4.2. Increase the ability to flow funds in a timely manner to meet researchers' needs, shortening the time it takes for peer review, decision, and communication of the decision;

- 4.3. Offer grants with longer duration (or at least more flexibility in duration); and

- 4.4. Establish clear timelines, milestones, tracking/monitoring systems and overall adherence to timelines and reaching milestones (i.e. reporting guidelines to capture the commercialization impact).

| Recommendation | Response (Agree or Disagree) |

Management Action Plan | Responsibility | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CIHR should adopt a definition of innovation that captures the broader social, economic and health benefits resulting from the use of health research to develop or improve goods, services, processes, organizations and systems. | Agree | CIHR will adopt this broader definition as it develops a new strategy. | Vice-President External Affairs and Business Development | Develop Strategy - 2015-16 |

| 2. CIHR should continue to fund early stage commercialization research to support this critical phase in the commercialization process to test and validate the commercial potential of discoveries that addresses a key funding gap and unmet need among researchers and TTOs. | Agree | Through the design of the new Open funding schemes, CIHR has taken measures to remove barriers and encourage innovative research. CIHR is committed to ensuring that this type of research continues to be well supported through the transition to the new Open funding schemes. | Chief Scientific Officer/Vice–President, Research, Knowledge Translation ad Ethics Portfolio | Through the implementation of the Project Scheme Pilot - 2016-17 and on-going |

3. CIHR should play a brokerage role in the area of innovation and commercialization and focus on:

|

Agree | CIHR will develop a new strategy, which will appropriately define CIHR's brokering role in this regard. | Vice-President External Affairs and Business Development | Develop Strategy, including definition of CIHR's brokering role - 2015-16 |

|

4. CIHR should incorporate the following into the future design and delivery of commercialization programs:

|

Agree | CIHR, through the implementation of the new Open schemes and the college of reviewers, is implementing an application focused review that will ensure that the appropriate expertise is assigned to each application. Further, CIHR is taking steps to engage more industry experts in the peer review process. Finally, by rolling the existing open programs into the new Open schemes applicants conducting this type of research will benefit from increased flexibility with respect to funding limits and grant duration. Any new programming developed as part of CIHR's new strategy will appropriately incorporate these design considerations. |

Chief Scientific Officer/Vice–President, Research, Knowledge Translation and Ethics Portfolio and Vice-President External Affairs and Business Development |

Through the implementation of the Project Scheme Pilot - 2016-17 and on-going. and Incorporating of design elements into new programs if required to support strategy - 2016-17 |

1. Evaluation Scope & Purpose

In 2005 CIHR developed its Commercialization and Innovation Strategy (CIHR, 2005) with the goal to provide a coherent framework for transforming health research into action, improving the quality of life and stimulating economic development through discovery and innovation. The strategy had specific objectives developed in four strategic areas: research, linkage, talent, and capital, and it was implemented through a series of programs, initiatives, national platforms, and other activities.

Evaluation scope

Following consultations with senior management and the strategic leads of the CIHR commercialization programs, the scope of this evaluation focused on the following current CIHR commercialization programs:

- Industry-Partnered Collaborative Research Operating Grants (IPCR);

- Collaborative Health Research Projects (CHRP)Footnote 1;

- Science to Business (S2B);

- Proof of Principle Phase I (POP I); and

- Proof of Principle Phase II (POP II)Footnote 2.

The evaluation covers the period of time since each of these programs started until 2012/2013.

Evaluation purpose

The evaluation measured the success CIHR's commercialization programs in terms of: knowledge creation, knowledge translation and commercialization outcomes, collaboration and partnership, and capacity building, design and delivery. To better understand CIHR's commercialization programs' achievements and when suitable, comparisons were made with the following programs:

- A sample of Open Operating Grants Program (OOGP) funded researchers who have been identified successful in commercialization (defined as having reported at least one of the CIHR's Research Reporting System (RRS) commercialization outcomes and did not hold any CIHR commercialization grants) (n=27);

- The OOGP funded researchers who reported using RRS (n=982);

- Regenerative Medicine and Nanomedicine Initiative (RMNI) (CIHR, 2013) which included RMNI funded researchers with strategic funding successful in commercialization (n=27); and

- Centre of Excellence for Commercialization and Research Program (CECR) funded through Networks of Excellence (NCE) Secretariat (NCE, 2012) – joint initiative between CIHR, NSERC, SSHRC, Industry Canada and Health Canada to support research and commercialization centres that bring together people, services, and research infrastructure to position Canada at the forefront of breakthrough innovations in priority areas (n=135).

A set of best practices and lessons learned for health research commercialization were captured during the discussions with the various stakeholders interviewed: Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs)' representatives, partners, investors and representatives of seven international funding agencies that support commercialization of health research (see Appendix I for details on methodology). They will be presented in each section when applicable.

2. Profile of CIHR's Commercialization Programs

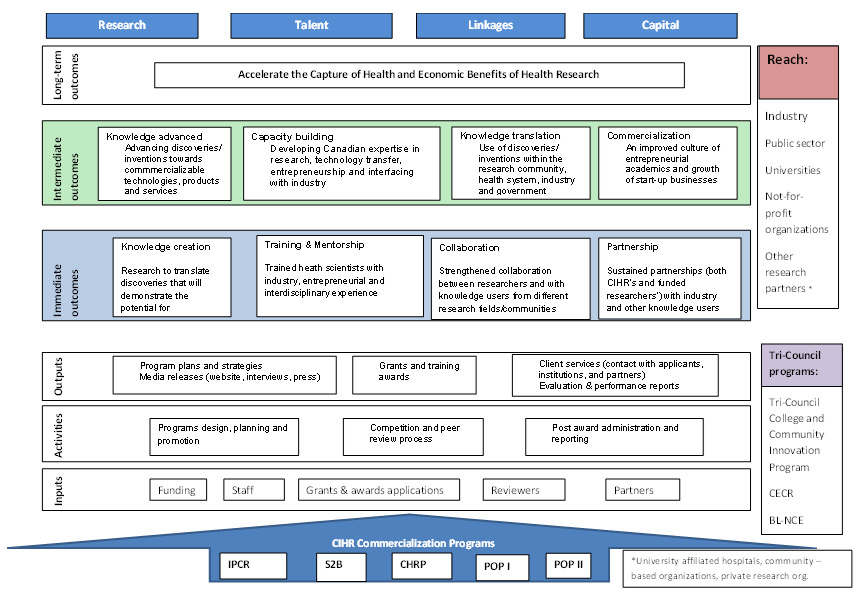

Each of the CIHR commercialization programs covered by evaluation address one or more of CIHR's commercialization strategy's four strategic areas: research, talent, linkages, capital:

- IPCR focuses on funding research that generates discoveries that may have potential for commercialization by facilitating university-industry collaborations in health research. It was created in 2005 as a merger of CIHR's Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) and Rx&D Collaborative Research Program.

- CHRP, originally launched by NSERC, was designed to build collaboration between researchers from NSERC and CIHR research communities to advance interdisciplinary research and train highly qualified personnel in interdisciplinary research. CIHR joined in 2003.

- S2B aims to develop talent by providing funding for individuals with a PhD in health research to pursue an MBA. It started in 2005 as a partnership with Canadian business schools to enable them to recruit PhDs in health research to pursue an MBA. Since 2010, the awards are provided directly to the MBA applicants.

- POP I & II address the capital needed for commercialization by advancing the discoveries/inventions towards commercializable technologies and creating new science-based businesses, with POP I starting in 2001 and POP II in 2003.

While each of these programs are focused on different stages in the commercialization process, it is recognized that commercialization is not a "linear" process, and each of them contribute to the overall strategic areas that CIHR wanted to influence though its commercialization strategy. While CHRP and IPCR focus on building collaborations between researchers and research users and generating research with potential for commercialization, they are not limited to only early stage commercialization processes. The research funded by these programs could also generate advanced stage commercialization outcomes such as patents and spin-offs. POPI and POPII were designed to address the more advanced commercialization outcomes. S2B was designed to enhance training; although, it should be noted that training was encouraged in all commercialization programs. Appendix II provides the Logic Model of the CIHR commercialization programs.

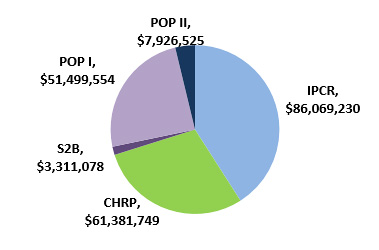

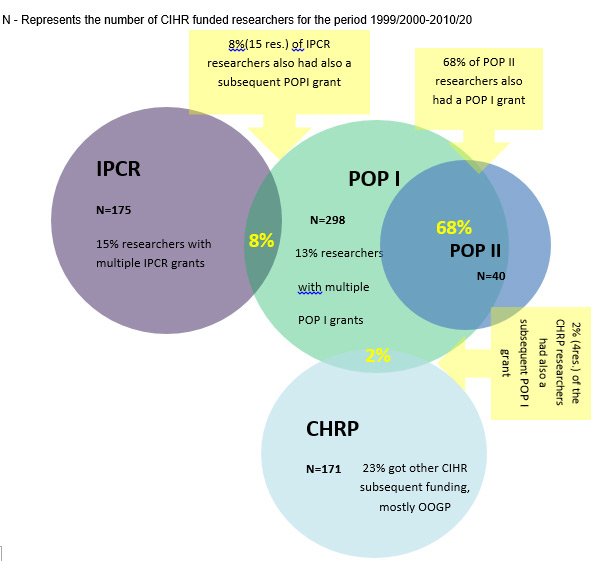

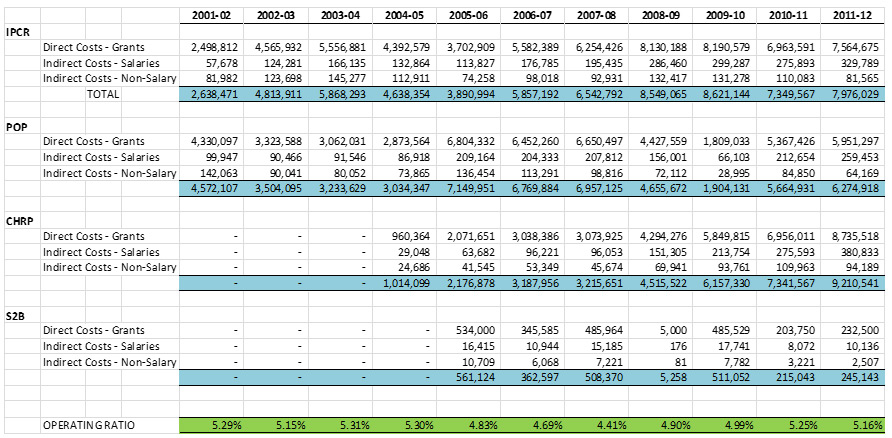

In 2012-2013 the total budget spent on the evaluated commercialization programs ($13,872,115) represented 1.7% of the total CIHR grant and awards expenditures. If we consider the other commercialization programs that CIHR delivers together with NSERC and SSHRC (Business-Led Networks of Centres of Excellence (BL-NCE) and CECRs), CIHR total expenditures on commercialization programming represented 2.9% ($28,193,643) of all expenditures, including flow-through programs mentioned above.

Figure 2: CIHR's investments in current commercialization programs since their creation*

Source: CIHR Electronic Information System (EIS) database

*CIHR commercialization programs have different durations; see program description for details.

-

Long description

CIHR Commercialization programs Financial investments IPCR $86,069,230 CHRP $61,381,749 S2B $3,311,078 POP I $51,499,554 POP II $7,926,525

3. Knowledge Translation & Commercialization

To what extent have the CIHR commercialization programs facilitated the application of health research, accelerate the commercialization of IP and promoted the establishment and growth of small businesses?

To what extent have the CIHR commercialization programs funded research that generates discoveries with potential for commercialization?

Key findings

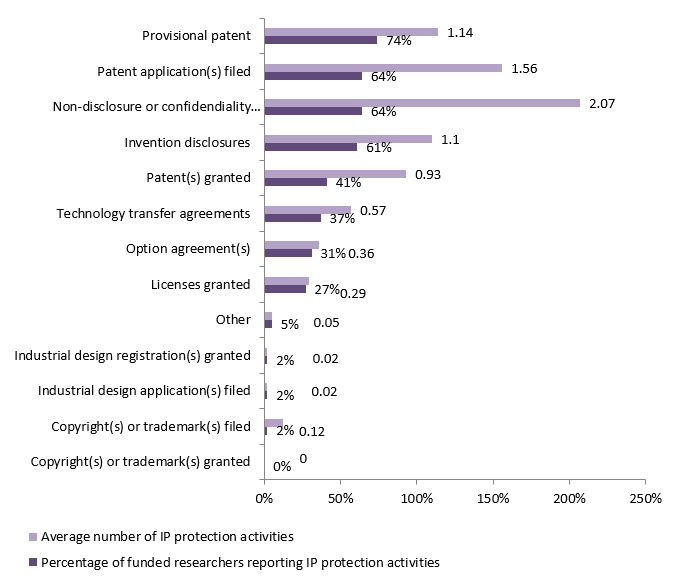

- Many of the CIHR commercialization funded researchers reported various IP protection activities: provisional patents (74%), patent applications (64%), non-disclosure and confidentiality agreements (64%), invention disclosures (61%), patents granted (41%).

- A minimum of 42 different spin-off companies have been created using CIHR commercialization programs funding from POPI and POP II programs since 2001.

- Researchers funded under POP I reported higher percentages for commercialization outcomes compared to all the other programs. OOGP researchers successful in commercialization, and researchers funded under CECR and RMNI programs, reported higher percentages for these commercialization outcomes compared to the IPCR and CHRP programs.

- Although generation of knowledge is not the main objective of POP I, the scientific productivity (i.e., journal articles published) of funded researchers normalized by grant duration and grant amount is similar to OOGP funded researchers.

- Due to the time lag necessary to attain a positive rate of return from an investment in research and technology transfer (up to 10 years at the institution/company level, and up to 20 years at the national level; patent time lag was found to be approximately 5 to 6 years) some of the impacts generated by the CIHR commercialization funding are still to be discovered in the future.

- Some of the stakeholders interviewed (TTO representatives, investors, partners) mentioned the challenges that researchers face in terms of pressure to be successful in their field by publishing and the lack of support researchers receive from their institutions when they express interest in translational research. However, commercialization and open science are not necessarily irreconcilable and could instead be envisioned as complementary elements of a more holistic innovation framework (Caulfield, 2012).

- Best practices in developing a strong culture of innovation include: movement from "commercialization" to "innovation" as a guiding philosophy; encouraging entrepreneurship and industry-pull programs; and "aggressive commercialization", which refers to a situation where resources are pooled to commercialize multiple discoveries in a given field (e.g. Green Chemistry in Canada).

Introduction

This section addresses two of the CIHR commercialization programs' objectives: knowledge translation (KT) with the application of health research results into practice (i.e., accelerate the commercialization of IP) and funding of research that generates discoveries with potential for commercialization.

Although all the programs were expected to contribute to both objectives, CHRP and IPCR were designed to address the early stage of health research commercialization by funding of research that generates discoveries with potential for commercialization, while POP I and POP II were designed to address the KT and more advanced stage of health research commercialization.

The performance of these programs was measured by looking at the following indicators for:

- measuring KT: number of presentations, participation in conferences and workshops;

- the commercialization of health research including intellectual property (IP)Footnote 3 protection: number of invention disclosures, patents, licenses, spin-offs; and

- the outcomes of research funding: the number of journal articles published or submitted and number of books/book chapters, reports/technical reports published.

Findings

KT activities conducted to advance knowledge

Most of the commercialization program funded researchers provided presentations to other researchers (72%) and to industry and other partners (79%). The next most common KT activity pursued by the funded researchers was participation in conferences, symposiums and workshops (74%) (See Table 3.1).

| Commercialization Programs (n= 72) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of Outcome | % of projects that produced at least 1 | Average produced per project |

| Presentations provided to researchers | 72% | 5.00 |

| Presentations provided to industry and other partners | 79% | 3.75 |

| Conferences, symposiums & workshops | 74% | 5.03 |

| Prizes/Professional awards | 31% | 0.61 |

| Newspaper articles | 31% | 4.25 |

| Magazine articles | 17% | 0.47 |

| Radio reports/ interviews | 21% | 0.67 |

| Television reports/ interviews | 25% | 0.69 |

| Internet articles | 17% | 2.60 |

| Facebook pages | 0% | 0.00 |

| Youtube postings | 8% | 0.18 |

| Blogs | 4% | 0.13 |

| Webinars | 1% | 0.03 |

Commercialization outcomes

Many of the CIHR commercialization funded researchers reported various IP protection activities: provisional patentsFootnote 4 (74% of funded researchers), patent applications filled (64%), non-disclosure and confidentiality agreements (64%), invention disclosures (61%), and patents granted (41%) (See figure 5.2). The most common IP protection activities reported were non-disclosure or confidentiality agreements (an average of 2), and patent applications filed (1.5), which would lead to an average of 0.9 patents granted per researcher (See figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1: Percentage of IPCR/POPI/POPII funded researchers surveyed (n= 59) reporting IP protection activities and average number of IP protection activities that have been pursued (survey data)

-

Long description

IP protection activities Percentage of funded researchers reporting IP protection activities Average number of IP protection activities Copyright(s) or trademark(s) granted 0% 0 Copyright(s) or trademark(s) filed 2% 0.12 Industrial design application(s) filed 2% 0.02 Industrial design registration(s) granted 2% 0.02 Other 5% 0.05 Licenses granted 27% 0.29 Option agreement(s) 31% 0.36 Technology transfer agreements 37% 0.57 Patent(s) granted 41% 0.93 Invention disclosures 61% 1.1 Non-disclosure or confidendiality agreement(s) 64% 2.07 Patent application(s) filed 64% 1.56 Provisional patent 74% 1.14

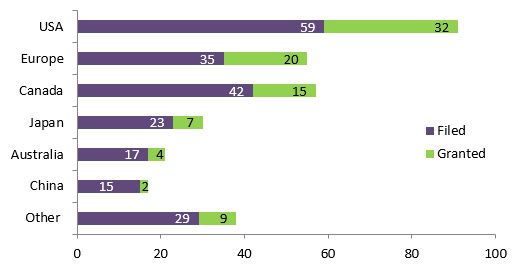

Most of the patent applications related to the projects funded under IPCR/POPI/POPII have been granted in the USA followed by Europe and Canada (See figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2: Number of patent application related to the projects funded under IPCR/POPI/POPII by jurisdiction

-

Long description

Number of patents Filed Granted Other 29 9 China 15 2 Australia 17 4 Japan 23 7 Canada 42 15 Europe 35 20 USA 59 32

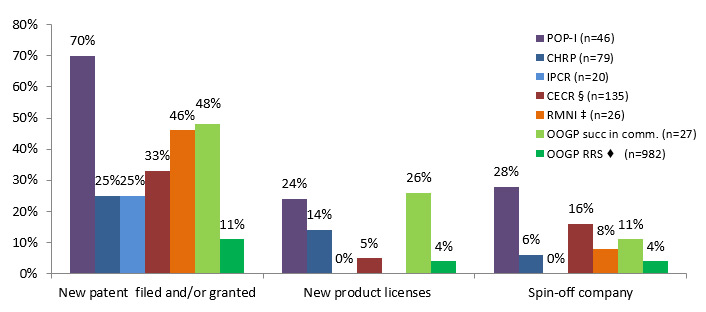

Assessing the programs separately, researchers funded under POP I reported higher percentages for filling patent applications, obtaining patents, non-disclosure or confidentiality agreements, invention disclosures and creating spin-offs compared to the other programs. OOGP researchers successful in commercialization, and researchers funded under CECR and RMNI programs, reported higher percentages for these commercialization outcomes compared to the IPCR and CHRP programs. (See Figure 3.3 and Table 3.2)

Figure 3.3: Percentage of researchers achieving the reported indicators; comparison with open and strategic funding

♦ OOGP-RRS-Patents filed or granted are reported together

‡ RMNI- includes new patents and new product license together, source : RMNI Evaluation

§ CECR data souce: Summative Evaluation of Network of Excellence – Centres of Excellence for Commercialization and Research program , June 2012, survey with 17 Centres, of which 12 Centres have Health as a priority area.

-

Long description

POP-I (n=46) CHRP (n=79) IPCR (n=20) CECR §(n=135) RMNI ‡(n=26) OOGP succ in comm. (n=27) OOGP RRS♦ (n=982) New patent filed and/or granted 70% 25% 25% 33% 46% 48% 11% New product licenses 24% 14% 0% 5% 26% 4% Spin-off company 28% 6% 0% 16% 8% 11% 4%

| POP-I (n=46) | POPII (n=6) | CHRP (n=79) | IPCR (n=20) | CECRFootnote i (n=135) |

RMNI (n=26) | OOGP success in comm. (n=27) | OOGP RRS (n=982) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patent application filed | 70% | 83% (5) | 25% | 25% | 33% | 46%Footnote ii | 48% | 11%Footnote iii |

| Patent granted | 37% | 83% (5) | 23% | 10% | 7% | 22% | ||

| Licenses granted | 24% | 83% (5) | 14% | 0% | 5% | 26% | 4% | |

| Non-disclosure or confidentiality agreement | 65% | 67% (4) | 9% | 20% | 44% | NA | 11% | NA |

| Spin-off company | 28% | 50% (3) | 6% | 0% | 16% | 8% | 11% | 4% |

Spin-offs

Spin-off companies may have been established to license a discovery, fund research in order to further develop a discovery that will be licensed to the company, or provide a service. 28% (n=54) of the researchers funded under POP I program and 4 researchers funded under POP II program established a spin-off company with the funding obtained from CIHR.

Analysis of POP I and POPII progress reports, along with survey data, revealed that a minimum of 42 different spin-off companies have been created or benefited using commercialization program funding from POPI and POPII since 2001.

Qualitative data derived from the progress reports provides more in-depth information on the success stories behind the spin-offs, of which a few examples are presented below in Table 3.3.

One of the important factors in assessing the impact of moving a discovery to commercialization is the long time lag that it takes a discovery to materialize into concrete economic benefits. According to Heher,(2006) it can take up to 10 years for an institution/company, and 20 years nationally, to attain a positive rate of return from an investment in research and technology transfer. The time lag differs between disciplines, therefore "in the field of nanotechnology for example, the patent time lag was found to be approximately five to six years" (Daim et al., 2007). As such, some of the impacts generated by the CIHR commercialization funding are still to be discovered in the future.

| Company Name | Principle Investigator | Area of Research | Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Prof. Shana Kelley, University of Toronto |

Rapid detection system on known cancer biomarkers in prostate tumor tissue as an indication of disease progression Developing the Xagenic X1 platform - a revolutionary diagnostic system that allows the user to perform molecular diagnostic lab-quality assays in the physician office. |

Large market opportunity created by significant unmet medical need for point-of-care diagnostic solutions Employs more than 40 people Revenues from worldwide sales of molecular diagnostics are estimated to be $6.2B in 2014. |

| Tissue Regeneration Therapeutics (TRT)

|

Dr. John Davies, University of Toronto |

Progressive biotechnology with a focus on the commercial development of patented Human Umbilical Cord PeriVascular Cell (HUCPVC) TRT has shown that the tissue around the vessels of the umbilical cord is the richest source of mesenchymal stem cells ever described |

2014- TRT and Héma-Québec enter a definitive licensing agreement for the first human clinical trial of TXP-1 2013 - TRT raises $3.25 Million to accelerate the development of its Mesenchymal Cell therapeutics platform |

|

Dr. Dwayne |

Novel laser surgery technique A picosecond laser surgery IP has been developed by the Miller Group at the University of Toronto, and Attodyne has been incorporated and is the intended vehicle for commercialization of this IP. |

Attodyne manufactures state-of-the-art picosecond lasers for micromachining, material processing, and research. Picosecond Lasers are used in a variety of industries, from the manufacturing of displays and mobile electronics, to medicine and bio-diagnostics. |

|

Dr. Stuart Foster and Dr. Brian Courtney, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre |

3D forward looking scanning mechanism for intravascular and intracardiac imaging. The technologies developed under the CIHR POP program have been licensed to Colibri Technologies Inc, which is a spin-off company from Sunnybrook. |

Colibri raised over $8.9MM of private investment, another $9MM of non-dilutive (mostly public) funding, created 25 full time jobs at Colibri, 6 full time research personnel positions at Sunnybrook and issued 10 US patents. |

Knowledge creation

Overall, of the CIHR commercialization programs funded researchers who responded to the surveys (n=72), 79% published at least one journal article, 28% published books/books chapters and 25% produced reports/technical reports; 45% of the IPCR funded researchers and 30% of the POPI funded researchers produces a joint publication with private sector. (Data not shown.)

However, it should be underlined that publications are not traditional commercialization outputs for these types of programs. The increased use of intellectual property rights (IPR) in scientific research has sparked a vigorous academic and policy debate over what is known as the "anti-commons effect." Specifically, the anti-commons hypothesis states that IPR may inhibit the free flow and diffusion of scientific knowledge and the ability of researchers to cumulatively build on each other's discoveries (Murray & Stern, 2007). Yet, other studies found that inventors publish significantly more and both activities actually reinforce each other (Van Looya et al., 2006).

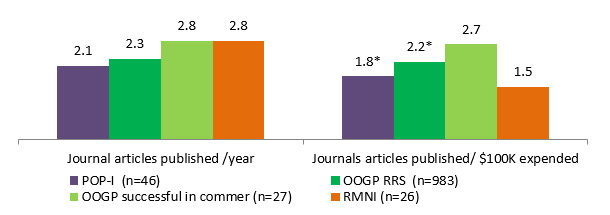

Comparison of journal articles between CIHR commercialization programs and OOGP

In order to compare average publications per grant we have to consider not only the differences in terms of the programs' objectives, but also the different durations and amounts of grants. Table 3.3, presents the average number of journal articles published normalized by the grant duration in years and the average grant amount for each program. Considering the very small number of POP II researchers who responded to the survey, these results are shown for information only.

| Program type | CHRP (n=145) | NORMALIZED DATA by individual projects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPCR (n=19) | POP-I (n=46) | POP-II (n=6) | OOGP RRS (n=983) | OOGP successful in comerFootnote vi (n=27) | RMNI (n=26) | ||

| Averages for overall program | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Average grant duration in years | 3 | 2.8 ± 1.3 | 1 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 | 3.7 ± 1.3 | 3.7 ± 1.4 | 3.5 ± 1.5 |

| Grant average | $320,676 | $288,290 ± $728,206 | $133,957± $27,613 |

$192,291 ± $88,280 | $437,260± $279,900 | $ 462,179 ± $251,464 | $855,302 ± $676,673 |

| Journal articles published | 5 | 5.5 ± 5.6 | 2.1 ± 2.5 | 5.3 ± 3.4 | 9.2 ± 12.5 | 11 ± 10.8 | 12.1 |

| Journal articles published /year | 1.6 | 2.1 ± 1.7 | 2.1 ± 2.5 | 5.3 ± 3.4 | 2.3 ± 2.6 | 2.8 ± 2.2 | 2.8 ± 2.6 |

| Journals/ $100K expended | 1.6 | 4 ± 3.7 | 1.8 ± 2.5Footnote v | 4.2 ± 4 | 2.2 ± 2.6Footnote v | 2.7 ± 2.3 | 1.5 ±1.9Footnote iv |

The OOGP Evaluation report (CIHR, 2012) states that publication of OOGP researchers peak in their third year of funding. CHRP has an average duration of 3 years and IPCR 2.6 years; however, POP I grants are one year in length. The results show that POPI and IPCR funded researchers produce 2.1 journal articles published per year, CHRP produced 1.6, compared with OOGP funded researchers who produced 2.3 journal articles per year. Due to the sample size and data availabilityFootnote 5, the comparison for the statistical difference was made for POP I and OOGP funded researchers. The only statistical difference between POP I and OOGP was found for journals articles produced per $100K: 1.8 for POP I and 2.2 for OOGP, but with a small difference Footnote 6 (See Figure 3.4). Although the sample size of the OOGP researchers successful in commercialization is small (n=27), they seem to produce more publications (2.7 journal articles per $100K) compared with the overall OOGP researchers (2.2) and POP I researchers (1.8).

Figure 3.4: Comparison of journal articles published between POP I, OOGP and RMNI; normalized results by grant duration and average grant amount.

*Due to the sample sizes, the statistical significance was tested only for POPI and OOGP RRS programs, and only these two values were found statistically significant, Mann-Whitney non-parametric test, p<0.05.

-

Long description

Program type POP-I (n=46) OOGP RRS (n=983) OOGP successful in commer(n=27) RMNI(n=26) Journal articles published /year 2.1 2.3 2.8 2.8 Journals articles published/ $100K expended 1.8 2.2 2.7 1.5

Challenges faced by researchers in commercializing their research

The interviews with TTO representatives, partners, and investors revealed some of the challenges that researchers face when publishing and commercializing their discoveries. Some TTO representatives mentioned that some researchers gather support for grant applications, licenses, etc. regardless of the assessed commercialization potential of the research. Others reported cases where researchers receiving CIHR grants solely focused on their publishing needs as opposed to patent considerations, which resulted in severely diminished outcomes for key stakeholders.

Some participants noted that researchers may feel that commercialization poses a greater risk than reward. Further, they noted that this is inherently a cultural issue that needs to be altered at the institutional level in order to enable greater facilitation of health research commercialization. The idea of a renowned researcher is still closely linked to those who dedicate their time to fundamental research and have their findings published in esteemed academic journals.

"…it's not all the investigators who are willing to accept to do translational research involved; the concept of doing applied research is sometimes badly perceived; it's not well promoted and encouraged in the academic setting – but if you really want to be a renowned researcher, it's not to do some applied research but you do fundamental basic research and get it published." (Investor/Valorization)

One of the partners also noted that academic researchers are under tremendous pressure to be successful in their field, by publishing and being "renowned" and this discourages them from taking risks.

Also related to the challenges that researchers face in commercializing their research, Caulfield (2012) draws attention to the inconsistencies between open science and commercialization policies in the case of three countries: Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. He discusses the increasing pressure on university researchers to commercialize their work and collaborate, share data and disseminate new knowledge quickly in order to foster scientific progress, meet humanitarian goals, and maximize the impact of their research. Caulfield argues that commercialization and open science are not necessarily irreconcilable and could instead be envisioned as complementary elements of a more holistic innovation framework. This is something that needs further attention in the future (Caulfield, 2012).

Best practices for Enabling a Culture of Innovation

Establishing a strong, innovative culture was recommended as one of the preliminary steps if Canada would like to achieve more success in the area of health research commercialization. Best practices in developing a strong culture of innovation include: movement from "commercialization" to "innovation" and "valorization" as a guiding philosophy; encourage entrepreneurship and industry-pull programs; and "aggressive commercialization".

-

Movement from "commercialization" to "innovation" and "valorization" as a guiding philosophy

The term "innovation" has been used by some of the international organizations consulted for the environmental scan to capture the broader societal benefits that the innovation process brings:

"Innovation are new or significantly improved goods, services, processes, organizational forms or marketing models that are introduced to enhance value creation and/or for the benefit of society." (Norway Research Council, based on the OECD's definition of innovation in the Oslo Manual); ("Innovation strategy" – Sweden, Norway, EU Horizon 2020).

Also the term valorisation is used by some European countries and among Francophone technology transfer offices such as UnivalorFootnote 7. Knowledge valorisation refers to the utilisation of scientific knowledge in practice. Examples include developing a product or a medicine, or applying scientific knowledge to a system or process (University of Amsterdam, 2015)Footnote 8. Valorisation is the use, for socio-economic purposes, of the results of research financed by public authorities. It represents society's direct and indirect return on the public sector's investment in research and development. (Luxembourg Portal for Innovation and Research, 2015)Footnote 9

In its 2005 Commercialization and Innovation Strategy (CIHR, 2005), CIHR defines commercialization and innovation as the KT processes by which research is translated through knowledge, expertise and skilled people between the science base and its user communities contributing to the economic competitiveness, effectiveness of public services and policy, and quality of life of Canadians.

Encourage entrepreneurship and industry-pull programs

Placing a strong emphasis on building-up entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship would foster commercialization of research discoveries. Countries with a strong entrepreneurship culture embedded in their innovation system (Israel & US) were seen as best examples.

Also the Council of Canadian Academics (CCA) assessment of Canada's business innovation demonstrates the need for a fundamental change of paradigm: away from the preoccupation with R&D supply-push toward a demand-pull perspective centred on the firm, the innovation ecosystem, and the factors that determine the choice of business strategy. (CCA, 2013)

"Aggressive commercialization"

One of the TTOs spoke of the "aggressive commercialization" model where resources are pooled to commercialize multiple discoveries in a given field. In Canada, this type of collaboration is encouraged by the CECR model. For example, in the area of Green Chemistry, a pooling of resources has helped increase the commercialization of university inventions by placing the right people and right resources in a central way to house every discovery in Green Chemistry from every university (i.e., Green Centre Canada). This enabled the amassment of adequate funding from federal and provincial funders as well as encouraged industry to get involved at the discovery stage. In their words:

"…we're doing the same kind of thing here with the CECRs out of the NCE. I'll give you an example of one we started here in the area of Green Chemistry; the problem is that no single university has the critical mass of a research base to support the infrastructure that you need to do commercialization properly so if you're going to do it, you have to do it on a national basis (…); so we did that in the area of Green Chemistry... because we had that critical mass we were able to get funding from the Federal government, the Provincial government to put the right kinds of people and the right kind of resources in place to do what I call aggressive commercialization – once you have all that in place, Industry comes to your door because they know that everything coming out of the university sector in Green Chemistry is going to come through this one stop – so it is not a problem getting Industry engaged at the right stage which is the discovery stage (TTO, POP-I/POP)"

4. Collaborations & Partnerships

To what extent have the CIHR commercialization programs facilitated interaction between people and institutions throughout the commercialization process?

Have CIHR commercialization programs generated sustainable partnerships?

Key findings

- The majority (68%) of CIHR commercialization funded researchers (IPCR, POP I and POPII) generated collaborations with other researchers/academics, 32% of them with health system/care practitioners and 21% with industry; 80% of CHRP funded researchers had established new relationships with other researchers as a result of their project.

- Industry was involved to a higher degree during all the stages in CIHR commercialization research compared to OOGP research; 81% of commercialization funded researchers said they involved industry for the end of grant KT activities, compared to 60% for OOGP funded researchers.

- Although not a requirement for the program, 65% of the POPI funded researchers involved partners during their funded projects. Many of the POPI funded researchers (69%) considered their relationships with partners successful and most of them (90%) maintained links with them after the grant ended. These relationships were, in most cases, research collaborations, resulting from formal or informal networking.

- The majority of the funded researchers under IPCR (70%) and POPI (69%) declared that the funding through CIHR commercialization programs was an incentive to work with a partner. The importance of having a partner on the project is highlighted by the fact that 66% of POPI and 60% of IPCR funded researchers would still have chosen to work with a partner if the dedicated funding was not available.

- The main reasons for working with a partner included partners' expertise and knowledge, and to ensure increased knowledge transfer and use. IPCR funded researchers stressed the importance of financial contributions from partners.

- Program eligibility - there is a misconception that the programs are restricting international partners. The current ratio requirement for the matching funds (1:1) is seen as appropriate, but smaller companies had more difficulty with matching the funds.

- Challenges identified by the industry partners were: the cultural differences between industry and academia; the lack of control of the companies over research funds (i.e., researchers might divert from the original plans); monitoring project performance; and a need for better alignment between industry needs and timelines and CIHR competition frequency.

- Best practices for Enhancing Partnership:

- promoting the grants that are specifically designed to strengthen engagement and partnership (e.g. NSERC's Interaction and Engage grants)

- involving multinational companies and have R&D agreements with partners early on

- offer programs in partnership with other relevant organizations

- increase the awareness of new discoveries: organize workshops, seminars, organized exchange of ideas, so that researchers can find "takers" for their good ideas.

Introduction

Partnership and collaboration are central objectives for CIHR commercialization programs to ensure the stakeholders are involved early in the project so that "research uptake" increases. They are often used inter-changeably, but for the purpose of this study we used the following definitionsFootnote 10:

- Collaborations – an informal relationship, which may vary in intensity, complexity and level of engagement depending on the nature of the research process, the research stage and on the needs of the particular knowledge user.

- Partnership – a relationship that is formalized with a letter/protocol detailing how partners will be involved in the study and how they will contribute with financial or in-kind resources.

Some of the CIHR commercialization programs, such as IPCR and POP II, had as a requirement, the involvement of a partner from the very beginning of the application stage. Applications are submitted jointly by the applicant and partner with the partner matching CIHR funds at a specified ratio designated by program. In the past, both IPCR and POP II required an Applicant Partner to contribute two-thirds of the funding for the grant. Since 2010 the minimum partner contribution (including eligible in-kind) must be at least a 1:1 ratio. In 2011, CHRP made partner contribution a mandatory requirement.

Findings

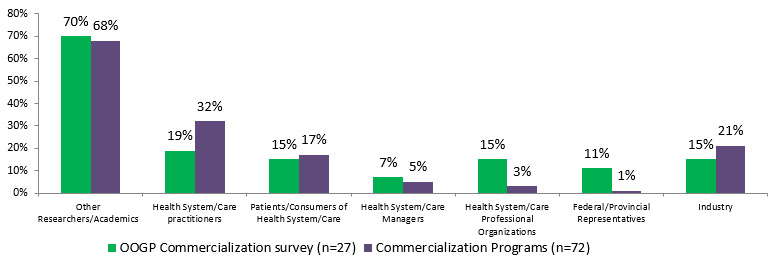

The majority (68%) of CIHR commercialization funded researchers (IPCR, POP I and POPII) had collaborations with other researchers/academics, 32% of them with health system/care practitioners and 21% with industry. The evaluation of CHRP shows that a majority of CHRP funded researchers (80%) had established new relationships with an average of 1.5 researchers as a result of their project. The relationships between health and NSE researchers have also often been maintained following the completion of the projects (73%).Footnote 11

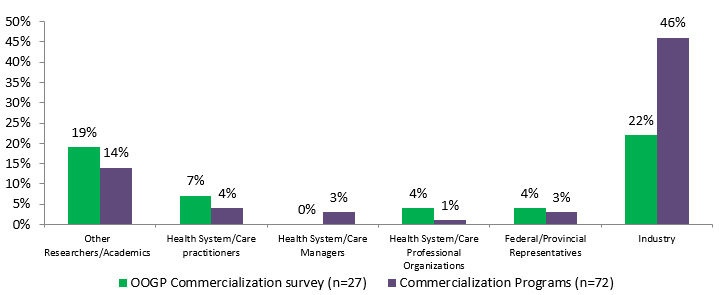

Figure 4.1: Percentage of researchers with other collaborations

-

Long description

Stakeholders OOGP Commercialization survey (n=27) Commercialization Programs (n=72) Other Researchers/Academics 70% 68% Health System/Care practitioners 19% 32% Patients/Consumers of Health System/Care 15% 17% Health System/Care Managers 7% 5% Health System/Care Professional Organizations 15% 3% Federal/Provincial Representatives 11% 1% Industry 15% 21%

Figure 4.2: Percentage of researchers with other formal partnerships

-

Long description

Styakeholders OOGP Commercialization survey (n=27) Commercialization Programs (n=72) Other Researchers/Academics 19% 14% Health System/Care practitioners 7% 4% Health System/Care Managers 0% 3% Health System/Care Professional Organizations 4% 1% Federal/Provincial Representatives 4% 3% Industry 22% 46%

Industry was involved to a higher degree during all stages of CIHR commercialization research compared to OOGP research; 81% of commercialization funded researchers said they involved industry for end of grant KT activities, compared to 60% for OOGP funded researchers.

Partnerships

Although not a requirement, 65% of the POPI funded researchers involved partners during their funded projects. POPII funded projects involved more partnerships per project, (average of 2.5) partnerships compared to other programs (1.0). IPCR had the longest partnership duration (range: 12-120 months). This may be because the average duration of IPCR grants was 2.6 years compared to one year for POPI and POPII grants. For the majority of POP II funded researchers (83%), and almost half (48%) of POP I funded researchers, these partnerships existed prior to the funded projects. (See table 4.1)

| IPCR (n=10-20)Footnote vii |

POPI (n=29-46)Footnote vii |

POPII (n=6) |

OOGP successful commercialization (n=10-27)Footnote vii |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At least one partner on the project | 100% | 65% | 100% | 37% |

| Average # of partnerships/ project | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| Average partnership duration (months) | 48Footnote viii | 20 | 37 | 24 |

| Average partner contribution | $947,404 | $143,256 | $1,644,444 | $191,428 |

| Partnerships existing prior funding | 15% | 48% | 83% | 40% |

| Maintained links with their partners after their CIHR grant ended | 60% | 90% | 83% | 80% |

| "In-kind" contributions Footnote ix | 25% | 46% | 83% | 19% |

The majority of POP II funded researchers (83%), almost half (46%) of POPI funded researchers and 25% of IPCR researchers reported receiving in kind contributions from their partners. These contributions were: access to expertise, equipment, personnel, time spent together developing a business plan, assistance making a commercial version of the product, conducting clinical surveys to assess product needs; estimating marketing and production costs for product, drug synthesis, preliminary toxicity experiments, technical support and analytical procedures, test kits and reagents, etc.

For the CHRP program, for the period of 1999-2008, while partnerships were encouraged, they were not a program requirement. The results of CHRP evaluation for the period specified above show that although only 16% of the projects identified a partner at the application stage, 40% of the researchers responding to the survey indicated that their projects involved partners.

Many of the POPI funded researchers (69%) considered their relationships with partners successful and most of them (90%) maintained links with them after the grant ended. These relationships were in most cases research collaborations, of being part of a formal or informal network.

| OOGP Comm. Survey (n=10) | IPCR (n=6) | POP-I (n=29) | POP-II (n=6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research collaboration | 60% | 83% | 62% | 50% |

| Consulting contract | 0% | 17% | 17% | 50% |

| Part of a formal network | 20% | 17% | 7% | 0% |

| Part of an informal network | 0% | 33% | 17% | 0% |

Importance of partnerships

The majority of the funded researchers under IPCR (70%) and POPI (69%) declared that the funding through CIHR commercialization programs was an incentive to work with a partner. The importance of having a partner on the project is highlighted by the fact that these funded researchers, 66% for POPI and 60% for IPCR would still have chosen to work with a partners if the dedicated funding through the CIHR commercialization programs would have not been available.

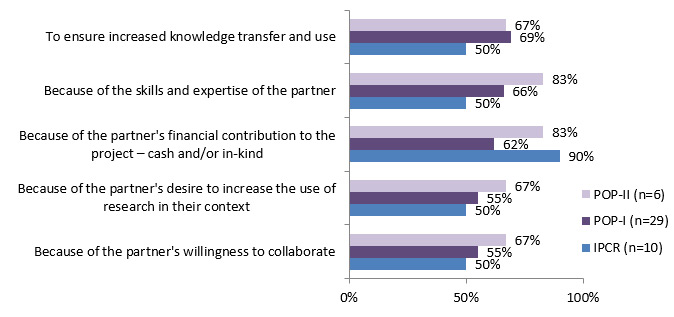

The main reasons for working with a partner included: partners' expertise and knowledge, and to ensure increased knowledge transfer and use. IPCR stressed the importance of financial contributions from partners as a reason to include them in research. (See figure 4.3)

Figure 4.3: Reasons for partnering

-

Long description

Reasons for partnering IPCR (n=10) POP I(n=29) POP II (n=6) Because of partner's willingness to collaborate 50% 55% 67% Because of partner's desire to increase the use of research in their context 50% 55% 67% Because of partner's financial contribution to the project - cash and/or in-kind 90% 62% 83% Because of skills and expertise of the partner 50% 66% 83% To ensure increased knowledge transfer and use 50% 69% 67%

Attracting international partners

During the stakeholder interviews, there were a few participants who perceived that their work was not eligible for CIHR commercialization grants because they could not attract a Canadian partner. It seemed to be a misconception that the CIHR commercialization programs restrict international partners. Participants felt that there is a definite need to acquire more international partners from the large pool of skills and resources available. One TTO felt strongly that Canada is not doing enough to tap into this pool of resources and help institutions to build their internal capacity to match external capacity.

Partner matching fund requirement (1:1)

The current ratio requirement for the matching funds (1:1) was seen as appropriate by the majority of researchers. However, some stakeholders interviewed had mixed feedback on this issue, identifying it as an ongoing challenge especially in the case of the POP-II. This was of particular problem when the partners are of small or medium size enterprises (SMEs). Still, several participants indicated that the matching funds allowed for a more robust budget for the research and should be continued.

In order to meet the diverse needs of the commercialization endeavors covered by CIHR's suite of grants, respondents suggested that CIHR take a case-by-case approach to determine the most appropriate matching fund requirements. This approach could take into account partner size and estimated costs for product development and commercialization.

Challenges identified for partnership

Cultural Differences between Academia and Industry

One recurring themes from the interviews with stakeholders was that researcher and industry agendas do not always align. One of the TTOs pointed out how industry is not interested in sponsoring research that is purely academic; there is no advantage or incentive for them to be involved. Additionally, sometimes industry hesitates to engage with universities/research centers because of the slow research administration bureaucracy coupled with the high risk associated with early stage discoveries.

On the other side, one of the partners also noted that academic researchers are under a tremendous pressure to be successful in their field, by publishing and being "renowned" and this pressure does not allow them to take a lot of risks (i.e., make mistakes). TTOs were also noted by partners to not always provide the right advice, suggesting "think they know it all". Although, it was recognized that the value TTOs bring is very much dependent on the individuals who make up the TTOs. One partner went as far as to say that without the funding incentive, industry would likely not choose to work with academics because of the many constraints.

"So I think the reason why people have looked to work with academics is because it has created another funding source. If all things were equal funding-wise, I think that the amount of work that industry would do with academics would be a small fraction of what it is now, unless it was to secure funding that is non-dilutive….Good early on, because the projects are small enough, you need the funding badly enough and you see that as a route to go, but then after you go through the kind of pain and hardships managing those relationships and deal with the funding aspects. I think, if people had the choice they wouldn't do it" (Partner, POP grant).

Industry Perceives Lack of Control over the Actual Work that is Being Done

Another hindrance to Industry, which prevents them from engaging in work directly with researchers, is the lack of control the companies feel that they have on the actual work that is being done. The participants voiced that once researchers receive CIHR grants, POP I for instance, they will revert to their curiosity driven mindset, diverting from the translational or commercialization needs of the company. This is widely seen as an ongoing issue.

Monitoring Performance – Differences in Practices

Partners who participated in both POP and IPCR projects discussed the differences in culture in academic versus industry. Part of the differences was related to the nature of how projects are managed, controlled and accounted for (contractual and financial obligations) particularly in terms of deliverables against resources. Projects that are solely industry sponsored are viewed as having greater oversight and accountability. Projects that are partly public funded and partly industries funded are difficult to manage because the investigators get mixed messages (industry focuses on performance or milestone based funding). Overall, industry partners find that where the funds are administered and how the cash flow occurs is not very attractive. It was suggested that the idea of paying according to performance is something that CIHR could consider and this could also act as a way to measure success.

Other differences are related to how public versus corporate funds are used – e.g. level of risk that can be applied. By nature the POP projects tended to have greater risk and partners noted that these projects required greater public funding.

CIHR Competition Frequency

Having the CIHR competitions twice a year for some of the grants does not align well with industry needs and timelines. One stakeholder identified the challenge that if a company misses out on one competition, they have to wait up to six months for another opportunity to apply.

"This was an issue right from very start, so initially there was going to be a competition every two months so that companies would be slowed down and we wouldn't lose funding windows. Now, over the years because of the effort involved with the peer review became twice a year. So if you miss one of the competition, you have to wait, sometimes five or six months till the next competition and then you have to wait, sometimes up to eight or nine months, for the peer review process and transmission of result, approval, all that stuff. So it can over a year, and by then the company has gone cold, the ideas are not hot anymore." (Partner, IPCR)

Best practices for Enhancing Partnership:

The following best practices and lessons learned were suggested to address the cultural disconnect between academia and Industry during the interviews with various stakeholders:

- Broadening and strengthening the networks for both researchers and Industry; very strong networks in geographically and demographically small countries (i.e. Israel, Norway) seem to be a success

- Involving multinational companies and have R&D agreements with partners early on

- Offer programs in partnership with other relevant organizations (e.g. US-National Institutes of Health (NIH) programs. Some examples are:

- Niche Assessment Program and Commercialization Assistance Program are offered in collaboration with Larta Institute of Los Angeles

- UK-Medical Research Council (MRC) program - Biomedical Catalyst funds SMEs in collaboration with Technology Strategy Board).

- Promoting the grants that are specifically designed to strengthen engagement and partnership; NSERC's Interaction and Engage grants were seen as a success in bringing together academia and industry.

- Increase the awareness of new discoveries - organize workshops, seminars, organized exchange of ideas, (e.g. forums to discuss new discoveries and latest interest from industry, a scouting program to canvas commercialization opportunities for industry), so that researchers can find "takers" for their good ideas.

- Non-monetary support programs were seen as very supportive; some examples of these programs are:

- Networking - Pipeline to Partnerships (P2P – US NIH), DEEP.com (European Commission), IRAP;

- Regional Innovation Networks (Alberta Innovates), Htx.ca (Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation.

5. Capacity development

Have the CIHR commercialization programs contributed to training highly qualified people in collaborative and interdisciplinary research with management expertise and in careers that support commercialization in Canada?

Key findings

- The majority (76%) of S2B awardees declared that the MBA program exceeded or fully met their expectations for developing their entrepreneurial/commercialization skills and knowledge.

- The MBAs contributed to the development of their commercialization skills/knowledge by: helping them gain new knowledge in the field of commercialization (92%), exposing them to networking opportunities with industry organizations (92%), helped them acquire business/entrepreneurial skills (92%), and provided them with opportunities that made them feel more "job-ready" (92%).

- At the time of survey, many S2B awardees (41%) were working for industry, for universities (technology transfer, industry liaison or other office) (18%), or non-for-profit organization (18%) and other organizations (23%).

- IPCR, POPI and POPII, involved a variety of HQP and research personnel in commercialization projects, but a low number of them were actually trained in the area of commercialization.

- According to half of the funded researchers, HQP and research personnel have been hired by academia and 40% of researchers reported HQP were hired by industry.

- Thirty percent of the funded researchers surveyed reported a lack of commercialization skills as a challenge in moving their discovery/innovation toward commercialization.

- There is a perceived shortage of entrepreneurs in Canada.

- Almost all participants voiced the need for TTO staff to have strong commercialization expertise.

- Best practices for capacity development:

- facilitation activities are seen to be more important than offering training opportunities

- granting agency facilitates the recruitment of specialists that assist the TTOs/researchers throughout the commercialization process

- experts within the agency that are continuously in touch with companies and have previous experience working in commercialization or industry.

Introduction

Training in the field of commercialization has been the main objective of S2B programFootnote 12 and has been encouraged through the other CIHR commercialization programs (CHRP, IPCR, POPI & POP II). S2B was specifically designed to build capacity of business-trained scientists in Canada by "encouraging individuals with a PhD in health research to pursue an MBA."

To assess these programs' performance in capacity development, the following indicators were studied: number of HQP involved in the projects and trained in the area of commercialization, extent to which the training contributed to relevant experiences in their field, and HQP career trajectory. Since the objective of the S2B program was mainly focused on training, comparing with the other CIHR commercialization programs, the findings will be presented separately for this program.

Findings

Initially S2B program was offered as a grant to Canadian business schools with health or biotechnology stream MBAs to enable them to recruit PHD scientist in health research. As of 2010, following the advice of Commercialization Advisory Committee, the funding is provided directly to the applicant as an award. The maximum award value is $30,000 a year for 2 years. Also the program expanded to include all Canadian MBA programs. The following results refer to the awards portion of the program.

Of 31 awardees, 17 responded to the evaluation survey, representing a 55% response rate. 41% of the awardees have already completed the MBA program and the remaining 59% are still pursuing their degree. The top reported reasons the awardees applied to an MBA through the S2B program were: to obtain additional training and experience in management (76%), to increase their employability (76%), for networking opportunities (i.e. industry organizations) (71%) and to obtain additional training and experience in entrepreneurship (59%).When asked how the MBA program met their expectations in term of contributing to the development of their management/entrepreneurial/commercialization skills/knowledge, 35% of the awardees said it exceeded their expectations, 41% declared that it fully met their expectations and 18% that it only partially met their expectations.

The reasons most of the awardees were content with how their MBAs contributed to the development of their commercialization skills/knowledge were: it helped them gain new knowledge in the field of commercialization (92%), they were exposed to networking opportunities with industry organizations (92%), they acquired business/entrepreneurial skills (92%) and they felt more "job-ready" (92%). For the awardees who declared that the MBA partially met their expectations for contributing to their commercialization skills (18%), the majority (75%) declared that they had not had enough exposure to industrially relevant projects.

The majority of the S2B awardees (76%) declared that they would not have been able to participate in the MBA program without the financial award received from CIHR.

In terms of career development, at the time of the survey (April-May 2013), 24% of the awardees hold a management position, 18% a technology transfer position, and the rest hold various positions in the following fields: health research, finance, technology development, and entrepreneurship. Most of the awardees (41%) were working for industry and the rest (18%) for universities (technology transfer, industry liaison or other office). The remaining worked at not-for-profit organizations and other organizations (18%). Most of them were located in Canada (88%), in the following provinces: Ontario (36%), Alberta (21%), British Columbia (21%), Saskatchewan (14%) and Quebec (7%).

In assessing IPCR, CHRP, POPI and POPII capacity development, funded researchers were asked to report the number of HQP involved in their projects as well as the ones trained in the area of commercialization. Commercialization funded researchers involved a variety of HQP and research personnel in their projects, however the number of HQP and research personnel trained in the area of commercialization were low across the commercialization programs, and also for the OOGP comparison group, as depicted by table 6.1.

| OOGP Comm. Survey n=26 | CHRPFootnote x | IPCR n=20 | POP-I n=45 | POP-II n=6 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involved | Trained | Trained | Involved | Trained | Involved | Trained | Involved | Trained | |

| Researchers | 2.71 | 0.07 | 2.2Footnote xi | 3.30 | 0.10 | 2.68 | 0.61 | 3.40 | 1 |

| Research assistants | 1.95 | 0.11 | 0 | 2.80 | 0 | 1.38 | 0.25 | 1.80 | 0.20 |

| Research technicians | 1.46 | 0.08 | 0 | 1.60 | 0.10 | 1.42 | 0.25 | 3.25 | 0 |

| Postdoctoral fellows (post-Ph.D.) | 2.08 | 0 | 1 | 1.42 | 0.17 | 1.53 | 0.62 | 2.67 | 0.67 |

| Post health professional degree | 2.50 | 0 | 0 | 4.33 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fellows not purs. Master's or PhD | 2.00 | 0 | 0 | 3.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| PhD students | 2.30 | 0.05 | 1.7 | 2.42 | 0.17 | 1.81 | 0.52 | 1.75 | 0.50 |

| Master's students | 2.44 | 0.06 | 2.3 | 2.62 | 0.08 | 1.78 | 0.11 | 3 | 0 |

| Undergraduate students | 4.29 | 0 | 2.1 | 3.63 | 0 | 2.07 | 0.21 | 4.67 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |