A perfect pair: Why health research and urban planning go hand in hand

When Dr. Daniel Fuller was a teenager growing up in Saskatoon, he used to ride his bicycle through the city to get to the South Saskatchewan River where he spent most of his summers kayaking. He remembers thinking about the many ways that the city's urban environment promoted – or, in some cases, hindered – his ability to be physically active.

"Our built environment has a huge impact on our physical activity and health," he says. "Growing up, I was lucky to live in a city that had safe streets that I could bike along, and a nearby river and boathouse where I could go kayaking with friends. But that isn't the case for all Canadians. Many cities and towns don't have the same amenities or infrastructure."

What started as a mere observation during his teenage years eventually grew into a decades-long career exploring how the development and structure of cities can help improve the health of the people that live there.

As an associate professor and researcher in the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Medicine, Dr. Fuller and his team work with interdisciplinary scientists, urban planners, municipalities, and local community organizations across Canada to understand how different interventions – from bicycle share programs, to bridge construction, to snow clearing services – can help create healthier cities and enable Canadians to be more active.

"We want to encourage Canadians to be more physically active; even just ten more minutes a day can make a big difference," he says. "But being healthy is about more than just going for daily walks or buying a gym membership. We have to understand how the urban environment in which people live affects their overall health. For example, do they have access to safe paths or low-traffic streets where they can walk or bike outdoors? Are there public parks nearby where they can play? Do they live close to public transportation so they can get from their house to their workplace or school? These are all things that contribute to healthy cities and, in turn, healthy Canadians."

Using technology to build healthier cities

To promote physical activity and wellbeing in cities of all sizes, Dr. Fuller emphasizes that the first step should always be about understanding where – and why – there is need for improvement in the first place.

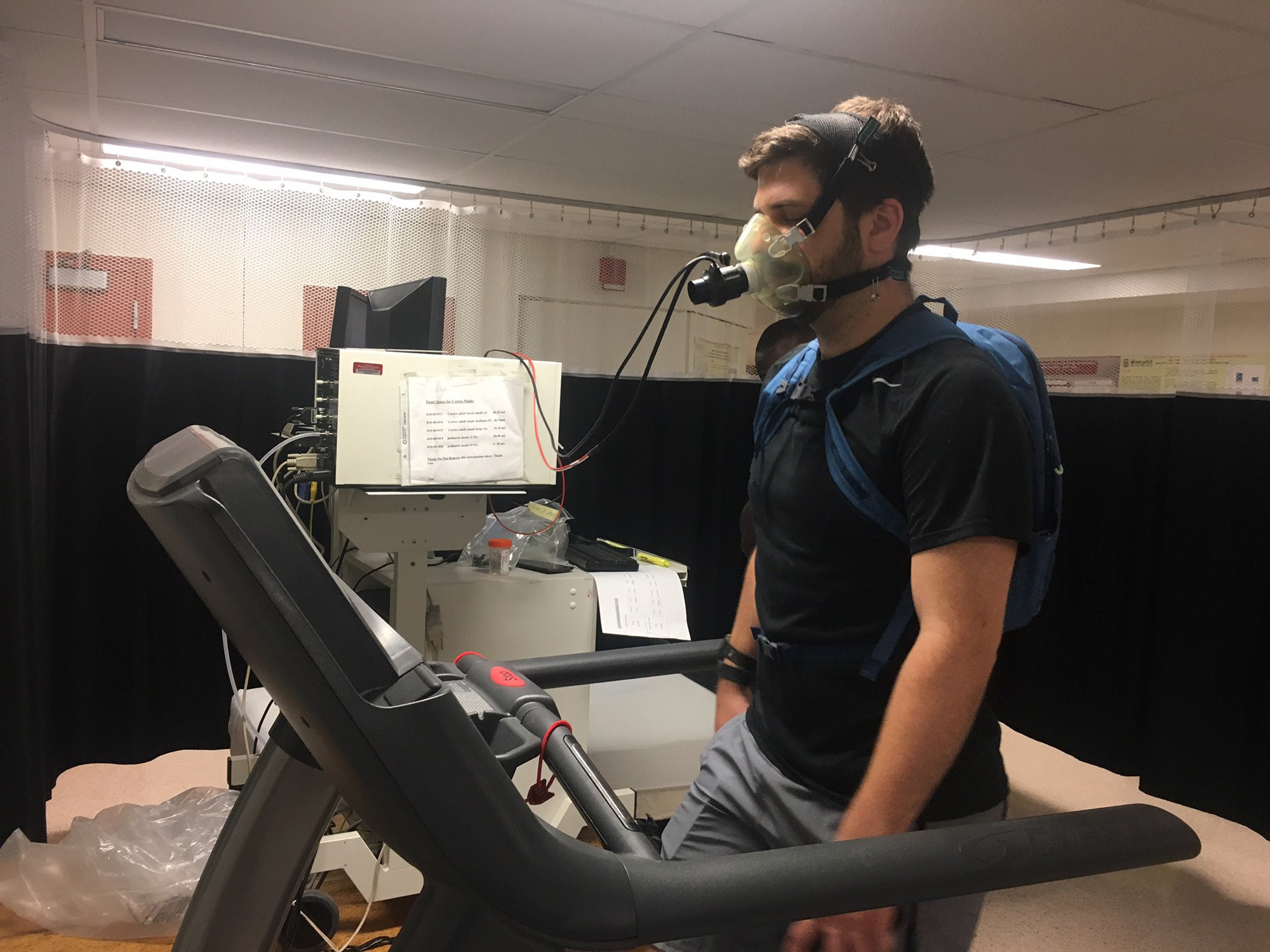

"If we really want to understand the challenges or opportunities that a city's environment poses for residents' physical activity, we need to get better at measuring people's activity, movement, and fitness in real-time," he says, noting the need for in-depth data in these areas to support everything from building new infrastructure to creating new services. "That's why, in our research, we're using technology like GPS trackers, wearable fitness devices, and smartphone apps to collect more accurate, real-time data of Canadians' physical activity."

One of the primary projects Dr. Fuller is leading to collect this information is the INTerventions, Research and Action in Cities Team cohort study, or INTERACT for short. Comprised of more than 50 researchers across Canada, the INTERACT team aims to assess how the built environment and urban change impact Canadians' health.

For this study, Dr. Fuller and his team recruited more than 1,900 participants in Victoria, Vancouver, Saskatoon, and Montreal. Participants first completed an online survey that measured their health and wellbeing, physical activity, social participation, travel behaviour, and socio-demographic characteristics. They then downloaded an app on their phone that used a GPS and fitness tracker to monitor their location and physical activity for 30 days.

Once the survey was completed and the app was installed, participants were told to go about their life as they normally would, including going to work, picking up groceries, seeing friends, working out, travelling to appointments, and more. In the meantime, Dr. Fuller and his team were collecting and comparing data about participants' activity levels across all four cities.

"We are only in the first phase of this project, which is focused on collecting and analyzing baseline data," Dr. Fuller says. "But we now know that with a combination of surveys, GPS trackers and smartphone apps, we can get a really clear picture of Canadians' physical activity levels, and understand how the built environment in their city affects their ability to be active. All of this data is helping us to better understand how we can build healthier cities across Canada."

Reducing social inequalities in health

Ultimately, Dr. Fuller's hope is that his research will help equitably increase physical activity for the entire Canadian population. "We know that good urban design can help improve the health and wellbeing of Canadians, but the outcomes often aren't equal for everyone," he says.

For example, research shows that people living in wealthier neighbourhoods are often healthier, more active, and more connected to their community. They often have urban infrastructure that makes it easier for them to walk to the grocery store and shops, they live close to a bus or subway stop, and there are parks, walking paths, and social services nearby.

"This type of infrastructure that promotes physical activity and wellbeing tends to be implemented in wealthier neighbourhoods because these neighbourhoods have more influence and can advocate for change – and unfortunately, the opposite is also true," Dr. Fuller continues.

Although studies have also found that residents in lower-income neighbourhoods tend to walk and bike more than those living in higher-income neighbourhoods, it is usually out of necessity and may not always be in safe environments. These residents may need to walk several kilometers to get to the closest bus stop, for example, or bike along a busy highway to get to the grocery store or access social services.

"In these cases, yes, residents are being active, but not for the right reasons," he says. "We want to build cities in ways that eliminate these inequalities and enable all residents to live healthy, active lives – no matter their age or income. And this should also include considerations for residents with mobility or other health issues, too."

For Dr. Fuller, addressing such gaps and promoting physical activity for all Canadians requires a much more intentional integration of health research and urban planning, but he's confident that projects like INTERACT will help to get us there.

"Many people think that our cities are made up of concrete and asphalt and are therefore very static, but in reality, cities are dynamic and malleable," he says. "And as work like ours progresses, I believe this combination of health and urban planning will create a new vision for our cities that is inclusive, sustainable, and supportive of everyone who lives there."

- Date modified: